In this exclusive interview, ETNZ’s Chase Zero Project Manager, Geoff Senior, provides HMS with a fascinating first-hand insight into ETNZ’s personal quest for ultimate marine hydrogen performance.

Can you relate how and why the decision came about to design and build a hydrogen-powered boat?

After winning the 36th America’s Cup, you have the opportunity to ‘shape’ the direction of the next event. The America’s Cup as a global event with technology at its core is at the pinnacle of international sailing and marine industries, so it has an opportunity to lead by example, and sustainability is clearly one avenue where the event can show the way. One specific area that has a lot of room for improvement concerns the fuel consumption of the chase boats that follow the AC75s around each day. However, from experience we know that batteries alone would not be able to do the job due to the long periods at sea. Hydrogen is obviously a new technology that is making headway in the motor vehicle industry, but it hasn’t really made any headway into the marine sector yet. So this is a prime opportunity to try to push hydrogen technology in the America’s Cup and prove it as a successful use case that will have a significant impact on the emissions of the teams in AC37, but also have a significant trickle-down effect on the global marine industry.

Who could lay claim to being the ‘brainchild’ behind the project, and how many in total are responsible for working on the design and build?

Certainly, Grant Dalton has been the champion and the brainchild behind the concept. I am the Project Manager, and Michael Rasmussen is the ETNZ technical lead on the hydrogen powertrain. Around 18 boatbuilders, three designers, two marine engineers, three electrical engineers and one mechatronic engineer have been involved in the project.

Did you consider other designs and explore prototyping other concepts/power alternatives?

We did do some rough calculations for a purely electric boat (with batteries only), but it was very evident early on that we couldn’t meet the range requirements of the chase boats on the water each day, so using batteries alone would not be fit for purpose.

What were some of the initial challenges the project faced in its early stages of development?

The short time frame from concept to launch date has created the largest challenge. This was compounded by supply chain issues for the powertrain components. Furthermore, less than one month into construction last year, a COVID lockdown in Auckland put the construction on hold for five weeks.

To what extent did the choice of power influence the design of the craft itself?

To what extent did the choice of power influence the design of the craft itself?

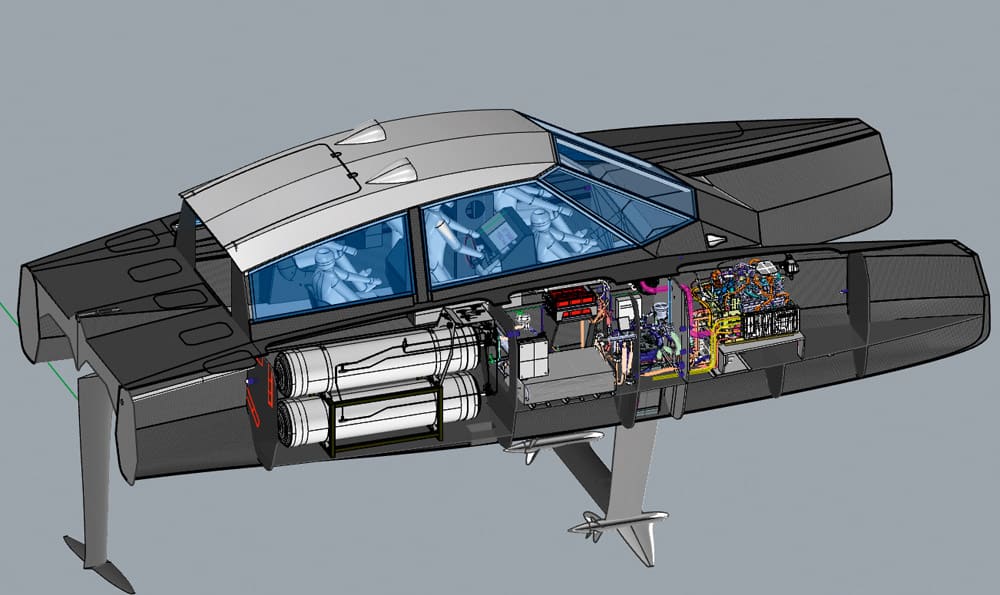

We went with a catamaran for several reasons, but one consideration was to try and keep enough room for the powertrain components in the hulls, while still giving adequate passenger space above for the crew to do their work necessary for a day on the water.

What technology, computer based or otherwise, was used in the process of the design?

Like any design work undertaken at Emirates Team New Zealand, we utilised our design tools across the board, including our simulator that we use for our America’s Cup design work. So we are continuing to push the boundaries and innovate with all projects we do, but also continually aiming to keep developing our tools in parallel.

Did the project at any time hit a ‘dead end’ necessitating finding a major alternative solution?

As with any new technology, there were a lot of iterations, and these will continue well into the commissioning and future vessels. One obvious one is the interaction of power and weight. To meet the specifications, we would often be looking for more power, which then leads to adding more weight, meaning the power goes up again. It’s a bit of a snowball but we have hopefully found a solution where we can meet the specification within the available technology.

At what point did the team feel fully confident that their concept was going to be 100% successful?

We reached the conclusion that the concept was ‘doable’ early on after a robust feasibility study where we looked at all aspects of the project and the ability to achieve the overall objective. Clearly we wouldn’t have started if we weren’t highly confident that the concept was going to work. However, in saying that, supply chain issues continue to raise ongoing challenges in the commissioning sequence, but that shouldn’t affect the overall success of the concept.

Besides fulfilling your own initial obligations to the team and their activities, do you have wider commercial applications in mind?

Absolutely. That has been one of the driving factors in the project – how we can influence the global marine industry by producing a prototype hydrogen-powered foiling catamaran. We have no doubt there will be a number of entities or organisations that will be watching and thinking how the technology can be adapted to their specific use case or ideas.

Compared to the current forms of renewable power technologies being explored for use in the marine sector, what potential do you foresee hydrogen power having? Could this be the new ‘fuel’ to power the global outboard market, for example?

Yes, absolutely – hence the objective of proving it can be done with this project. Hydrogen has a much higher energy density than the current battery technology, and batteries are unsuitable in any marine applications that need power for more than a couple of hours – not least in long-distance marine transport. To extract electrical power from hydrogen you need a fuel cell on board; this electrical power then drives motors that propel the vessel. Fuel cell technology is growing daily, and we see huge potential for high-energy and medium- to long-distance applications where the mass of batteries needed to store the equivalent energy required makes it unfeasible.

Is it your hope that your pioneering work will inspire others to explore this technology and popularise further?

Yes, that’s the driving factor in taking this project on.

Could you see a time when your knowledge and experience in this field of technology could attract the attention of some of the world’s major engine and/or boat manufacturers?

Like any prototype or innovation, it can attract others to the technology. We have been very fortunate to partner with Toyota Global, who have provided the prototype fuel cells that are a key component of the boat. They have been great partners and we hope this project will be mutually beneficial to everyone involved.

Do you have plans to build further hydrogen-powered, offshore-orientated craft of this type?

Not at this stage in terms of offshore. We are aiming to prove this prototype and the specific use case for this America’s Cup cycle, which is anticipated in a fleet to be used for this AC.

What would you estimate has been, or will be, the final cost of the design and development of your hydrogen-powered chase boat?

Certainly, as a prototype, we have designed it in a way that it can then be put into production once it has undertaken its sea trials and proving. The aim, therefore, is to produce it at a competitive price point.

ETNZ project team members

- Project manager: Geoff Senior

- Naval architect: Bobby Kleinschmit

- Mechanical engineer: Luke McAllum

- Electrical engineer: Michael Rasmussen

- Flight control engineer: Nick Goodson

- Build facility production manager: Scott Stokes

External project team members:

- Structural engineering: Gurit (Asia Pacific) Limited

- Hydrogen powertrain: Global Bus Ventures NZ

Chase Zero profile

- LOA: 10m

- Beam: 4.5m

- Draught: 2.2m

- Foil configuration: Primary π-foil, single T-rudder

- Displacement: 4800kg

- Fuel cells: 2 x Toyota 80kW

- Motors: 2 x 220kW

- Batteries: 2 x 42kWh

- Tanks: 4 x 8kg hydrogen @ 350bar

- Cruise speed: 30 knots

- Range: 180km (estimated, typical chase boat working cycle)

- Top speed: 50 knots (estimated)