International marine biologist and journalist Giovanna Fasanelli takes a fascinating look at the subject of ‘venom in the sea’ and considers both the role it plays and why, as boating people, we should be interested …

Most of us are well aware of the dangers that certain venomous spiders, scorpions and snakes pose to us landlubbers, but on a family holiday to the tropics (and how we must all be yearning for one following a gruelling global pandemic), how worried should we be when we plunge into that aqua-blue sea? As it turns out, very – and yet not at all. There are just a few easy rules to follow. Before we begin, an important note regarding the frequent misuse of the terms ‘venomous’ and ‘poisonous’: an animal is correctly said to be venomous when it injects its toxins by way of a bite or sting, while a poisonous creature is one that is toxic when eaten or whose poison passively penetrates the lungs or skin. The same toxins can be at play but the mode of delivery is key.

Rule No 1:

Avoid collecting shells, especially from under the water

In many cases, shells may appear to be empty, but the animal is often alive and hiding deep within. The fish-hunting cone snails are a powerful reason to obey this rule, for the detonation of their paralytic, neurotoxic, venom-loaded harpoons into your skin will warrant a screeching ambulance ride to the nearest hospital, and the wearing of gloves and wetsuits offers scant protection against the barbed spears of these larger cone species. Their alluringly attractive shells, geography and textile cones in particular have seen collectors being accidentally envenomated, and dozens have tragically lost their lives. Cone snail venom contains hundreds of bioactive peptides, referred to as ‘conotoxins’, and each species appears to manufacture its own special concoction that swiftly targets its victim’s neuromuscular systems. Paralysis is virtually instantaneous – useful for keeping the flightiest of

fish from escaping. The incredible diversity of chemical recipes found within this marine snail family is simply astounding and is a testament to their ability to adapt and optimise. In fact, cone snails duplicate their venom genes at a rate believed to be the fastest gene duplication in the animal kingdom. This genetic productivity means they are constantly churning out new cocktails of toxins that allow these silent predators the chance to continually respond to the availability of prey, and to stay ahead of any resistance their current victims may develop to their chemical arsenal. Simply put, cone snails are master chemists with an uncanny ability to hack the physiology of fish, worms and other molluscs around them.

Now, all this fancy chemistry hasn’t gone unnoticed by our biomedical researchers, and they are busy analysing the full gamut of conotoxins discovered thus far. Excitingly, there is great promise in the area of chronic pain management: one FDA-approved conotoxin, Prialt, is said to be a thousand times more effective than morphine, without the addictive side effects.

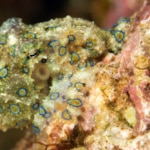

- All members of the expertly camouflaged scorpionfish family possess venomous spines that will, at the least, cause extreme pain and, at the worst, anaphylactic shock.

- Fire Urchins Magnificent fire Urchin Asthenosoma ijimai is capable of inflicting painful stings. © G.Fasanelli

- PUFFERFISH All pufferfish are poisonous and yet are enjoyed as a delicacy.

You can read more about cone snails’ devious tactics at https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2021/03/cone-snail-venom/618270

Rule No 2:

Avoid handling marine life and wear water shoes

Our skin is a pathetic protective barrier when it comes to the formidable defences of the many sea creatures that have been battling each other for millions of years, which is why touching these animals is to be avoided. While it is believed that all octopus, squid and cuttlefish are venomous (a thought for consideration at your next calamari and chips meal), a small number are on the ‘super-dangerous’ list! One bite from any of the four species of blue-ringed octopuses found around the Indo-Pacific will result in a highly distressed call for medical support. The surprising thing about these killers is their size: they are all small, so at 10–20 centimetres the empty shells lying in tidal pools and on reefs are attractive hiding places. Furthermore, unless they are flashing their blue rings as a warning signal or when excited, their camouflage renders them practically invisible. Their venom contains one of the most potent natural toxins known: tetrodotoxin (TTX). Fascinatingly, the manufacture of TTX is outsourced to the symbiotic bacteria living in the octopus’s salivary glands. This exceptional neurotoxin disrupts the transmission of signals from nerves to muscles by blocking the movement of sodium across neural membranes. Just 1 milligram of TTX is all that it takes to end a human life, and there is currently no antidote available. Once again, paralysis is swift, and victims often succumb to respiratory failure. Ironically, it is TTX’s paralysing effect that researchers are studying as a meaningful analgesic, especially for those suffering extreme cancer-related pain. It has even been shown to assist recovering heroin addicts by dampening cue-induced drug cravings and associated anxiety.

This may come as a no-brainer to many, but if a sea snake is encountered on your holiday, by all means enjoy the wonderful sighting, but you should definitely resist the urge to touch it. Despite this being an obvious rule, the number of people that break it is an embarrassment (artisanal and commercial fishermen aside). While most species have reputations for being very docile and small-fanged, and even if bitten the likelihood of envenomation is indeed very low, these snakes possess some of the deadliest venom of any on the planet. It really is a case of ‘which way would you rather be wrong?’ Receiving medical support and an antivenom can take hours, especially from remote tropical islands. Once again, a potent neurotoxin serves these predators by immediately subduing panicking fish, eels and crustacean prey that could otherwise easily escape.

- Fire Urchins – Fire urchins’ spines, though venomous, are enchantingly beautiful. © G.Fasanelli

- Flower Urchin – Don’t be fooled by this delicate posy of petals. The highly venomous flower urchin Toxopneustes pileolus can cause potentially lethal anaphylaxis.© Giovanna Fasanelli

- Clownfish – The famous clownfishes are immune to the stinging tentacles of their host anemone, the trick appears to be in the fish’s mucus which fails to detonate the anemone’s nematocysts.© Giovanna Fasanelli

Grab those thick-soled water shoes if you plan on fishing or frolicking in the warm shallow waters of reefs, tidal pools, estuaries or river mouths anywhere in the balmy Indian and Pacific oceans, for there are creatures whose primary defence against attack is spines, some of which you do not want close to your soft, spongy skin! All five members of the supremely camouflaged stonefish genus Synanceia are highly weaponized, with a pair of venom sacs positioned just below each of their 13 dorsal spines. Venom is discharged along ducts in the spines when the thick protective sheath covering them is punctured by applied pressure – the kind a clodhopping human hand or foot would cause. There will be no mistaking the situation as the list of ensuing symptoms is bewilderingly comprehensive: unbearable pain, swelling and necrosis at the wound site, secondary infection, prolonged kidney pain – and in more serious cases without swift medical assistance, convulsions, shock, respiratory and cardiovascular failure, paralysis and, potentially, eventually death … So watch your step!

- Left: Decorator crabs enjoy protection from predators by glueing stinging hydroid polyps to their carapace. © Giovanna Fasanelli

- Blue-ringed Octopus. © Giovanna Fasanelli

- Cuttlefish The saliva of most, if not all cuttlefish, octopus and squid is believed to carry venomous toxins. © G.Fasanelli

Video link: Milking a stonefish with Australian toxicologist Dr Jamie Seymour, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I8yJkIuvPvM

Often when a creature appears strikingly beautiful, there is a hidden message: stay away or be punished! The spines of the ineffably beautiful fire urchin will deliver a painful, though not deadly, sting. However, it is the infamous flower urchins of the genus Toxopneustes that one needs to keep a wary eye open for. The potent potion delivered by the petal-like pedicellariae can not only cause debilitating pain but can increase the risk of drowning due to muscular paralysis, disorientation and breathing difficulties, which may set in while underwater. Notwithstanding, they are popular among aquarists and are still considered a delicious delicacy worth the risk!

- Blue-ringed Octopus The saliva of the blue-ringed octopus contains a powerful neurotoxin tetrodotoxin which can lead to paralysis and respiratory failure. © G.Fasanelli

- Coleman Shrimp These gorgeous Coleman shrimp live symbiotically amongst the deadly spines of their fire urchin host Asthenosoma sp. © G.Fasanelli

- This diminutive beauty can spell disaster if its venom enters your bloodstream Blue-ringed octopus. © Giovanna Fasanelli

Rule No 3:

Swim, snorkel and dive in the sea wearing a full body skin suit (and avoid swimming altogether during the ‘stinger season’)

When it comes to standout venomous sea creatures, the incredibly dangerous box jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri, and its diminutive cousins, the Irukandji jellies, win all the awards. These animals hail from the phylum Cnidaria, which also includes corals, anemones and hydroids. The unifying feature of all group members is the presence of countless microscopic, venom-laden stinging cells known as ‘cnidocytes’ or ‘nematocysts’ that deliver their lethal serum into a victim’s skin via a spring-loaded harpoon. The venom’s toxicity to humans ranges from undetectable to ‘call an ambulance NOW’ and ‘who knows CPR?!’ The issue with Chironex fleckeri in particular is its enormous size and the number and length of its tentacles. The bell of these silent hunters can grow to the size of a basketball and from each of its four corners trail up to fifteen 3-metre-long tentacles that harbour over half a million nematocysts per square centimetre. The chances of surviving a comprehensive envenomation are slim as the venom is one of the most lethal and fast-acting currently known, resulting in excruciating pain and swift respiratory and cardiac arrest. Although an antivenom has existed (this time using hyperimmunised sheep) since the 1970s, there is a lot of controversy surrounding its efficacy, and much of the way the venom works in the human body is yet to be understood. Just think about the challenges researchers face in ‘milking’ a box jelly!

Video link: Watch the firing of nematocysts with Australian toxicologist Dr Jamie Seymour,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7WJCnC5ebf4

TTX is both a venom and a poison

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is produced by marine bacteria of the Vibrionaceae family and its presence can be observed in the tissues and organs of a number of metazoan animals. These animals are known among their would-be predators for being poisonous due to the presence of this potent toxin in their bodies. This is seen in some newts and amphibians and in a smattering of other marine invertebrates, but most famously in the pufferfish and certain of its tetraodontiform family allies. To this end, as TTX accumulates up the food chain that begins with these bacteria, it has been shown that, over time, pufferfish can lose their toxicity by being fed TTX-free diets. The blue-ringed octopus, however, has decided to use it as a powerful venom to be injected through a bite. But blue-ringed octopus mothers have been shown to pass on levels of this toxin to their developing eggs, which then renders them poisonous to predators!

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is produced by marine bacteria of the Vibrionaceae family and its presence can be observed in the tissues and organs of a number of metazoan animals. These animals are known among their would-be predators for being poisonous due to the presence of this potent toxin in their bodies. This is seen in some newts and amphibians and in a smattering of other marine invertebrates, but most famously in the pufferfish and certain of its tetraodontiform family allies. To this end, as TTX accumulates up the food chain that begins with these bacteria, it has been shown that, over time, pufferfish can lose their toxicity by being fed TTX-free diets. The blue-ringed octopus, however, has decided to use it as a powerful venom to be injected through a bite. But blue-ringed octopus mothers have been shown to pass on levels of this toxin to their developing eggs, which then renders them poisonous to predators!

Stung by a stone and rescued by a horse!

Stonefishes display some of the most striking camouflage of any fish in the world, and even when pulled in on a fishing net, people still make the error of assuming the algae-covered blob is an innocent rock, which is then mistakenly picked up and thrown back into the water. The toxin responsible in a stonefish sting is the protein-based verrucotoxin (VTX); fortunately, it can be denatured using heat, which is the most immediate first-aid response. While waiting for medical support, submerge the limb in hot (but not scalding) water – ideally around 44°C – for up to 90 minutes. In severe cases, a stonefish antivenom will be required. In Australia, this serum is the second-most administered antivenom after that issued for redback spider bites. It is made by immunising horses against the toxin, after which the blood-derived antibodies are collected and purified.

UK Jellyfish

Lions Mane Jellyfish Cyanea capillata.

Jellyfish species to avoid while enjoying coastal waters around the UK are the gargantuan lion’s mane, the compass and the mauve stinger jellyfish. The stings of these animals may be extremely painful and result in hospitalisation. Tempestuous weather has been known to dump flotillas of another unfriendly beast upon local beaches: the bluebottle or Portuguese man o’ war (Physalia physalis). The trick here is to know that these odd-looking creatures are not jellyfish but rather siphonophores – a composite colony of polyps known as ‘zooids’, which live together as a whole, each fulfilling separate life functions. Men o’ war are part of the cnidarian complex, which means their 10-metre-long tentacles house countless venom-bearing nematocysts that can unleash their fiery fury even after death.

https://www.thesun.co.uk/tech/12343614/most-dangerous-jellyfish-species-uk/

Conclusion

Venom is fascinating stuff – it can take a life but it can potentially save one too. The many complex chemical cocktails that venom represents have independently arisen across multiple lineages of animal life as an effective dual solution to two common challenges faced by wild animals: catching a meal and avoiding becoming one. But medical research is revealing the great potential these complex chemical recipes may have in the treatment of a range of human afflictions, including autoimmune diseases, cancer, diabetes, thrombosis, arthritis, psoriasis and chronic pain. There is even scope for putting spider toxins to work in the development of eco-friendly insecticides. This area of scientific research is thrilling, but none of this excitement may be enough to encourage you into the water after reading all this. However, I am here to tell you that after thousands of hours spent underwater in the tropics, and following countless encounters with many of these same venomous creatures (dangerous jellyfish aside), I have never needed to dial 911. I do, however, always stick to these simple common-sense rules. And if you are still really worried about being envenomated by, well, anything at all, follow Rule number 4: Don’t holiday in Australia!