Frank Kowalski, designer and skipper of Safehaven Marine’s Thunder Child II, recounts this vessel’s North Atlantic record run and Arctic Circle voyage – an adventure that encountered towering icebergs, vast ocean vistas, fog banks and mighty dwellers of the deep.

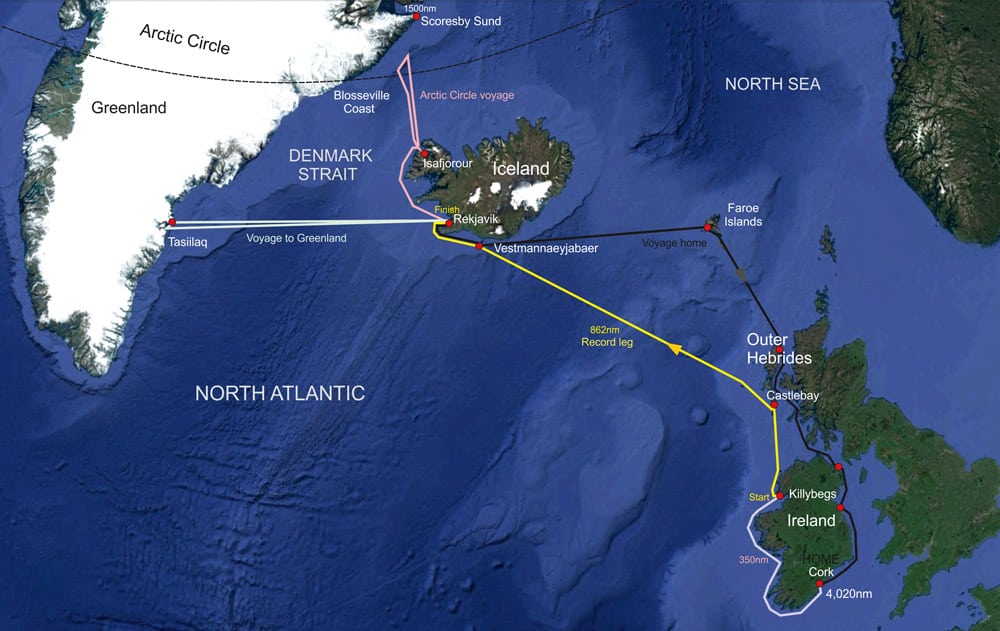

Regrettably, COVID-19 had put paid to our plans to undertake our transatlantic record attempt last year, and the continuing restrictions on travel also resulted in making the transatlantic run logistically too difficult to tackle this year as well. However, with Thunder Child II’s crew of five – skipper Frank Kowalski, navigator Ciaran Monks, drone pilot Carl Randalls, logistics expert Mary Power and engineer Robert Guzik – all vaccinated, we decided to undertake a shortened but still pretty extreme and challenging record run this summer. The new record attempt would be from Ireland to Iceland, taking in the first and longest leg of the original UIM record route: Killybegs, Ireland to Reykjavik, Iceland. Living on the boat, we then planned to continue voyaging to northern Iceland, before heading north-west, crossing the Arctic Circle line and on to the Greenland coast. We would then have achieved one of our long-standing ambitions, namely voyaging beyond the Arctic Circle to see an iceberg in Thunder Child II.

Casting off

Thunder Child II’s overall route

We sailed Thunder Child II from Cork to Killybegs a week ahead of when we expected a likely-looking weather window might appear after studying the long-range forecast. This would save us a full day’s travel during said window, a day of which would still be necessary to bring the boat the 350nm up the exposed Irish west coast. The weather window did indeed materialise, and on 7th July we drove up from Cork to board Thunder Child II that evening.

After taking on food provisions locally – mostly consisting of microwavable meals, sandwiches and a fair selection of enough junk food to last three days – we prepared the boat for departure at 3am on the morning of the 8th. The departure time was set by the need to arrive at Castle Bay in the Outer Hebrides after the daily ferry had docked and departed, as the easiest berth for our refuelling was at the ferry’s dock. We had a great deal of logistic support and help from Ruaridh MacLean, who arranged our fuel tanker and guided us in. Indeed, the support we received locally at the ports of call throughout our voyage proved invaluable, especially as a fast turnaround at the two refuelling stops was going to be essential in setting a good record time. The forecast had predicted winds dying down during the night of our departure, and indeed this proved to be the case. However, the residual 1.5m swell was on the nose leaving Killybegs, and this made for tough going at over 30 knots, especially during the night-time passage. This leg was a distance of some 170nm, and once we had cleared Malin Head, the north-westernmost tip of Ireland, and turned more north-east, conditions eased, and having gained shelter from the Outer Hebrides islands, and with a lightening fuel load, we were able to achieve over 40 knots for the final run to the island of Barra. Almost uniquely, Thunder Child II is more fuel-efficient the faster you go, so being able to keep the speed above 30 knots was critical in achieving the greatest range. If forced to slow down because of weather, our range was going to reduce, and this was going to produce a dilemma for us.

In our stride

We arrived at Castle Bay at around 8.45am. Thankfully the fuel tanker was waiting for us at the pier and we had a very efficient refuelling stop, with a good few of the local population of the island turning out to watch Thunder Child II arrive and depart. The island was fairly shrouded in mist while we were there, but we could still admire the rugged landscape, and of course the picturesque castle atop a small island in the bay, from which the town gains its name. The aforementioned dilemma we faced was the amount of fuel to take on board for the 562nm open ocean crossing across the North Atlantic to the coast of Iceland. Theoretically we should only have needed 5,500 litres, and my original plan was to take on 7,000 litres, which I felt gave a safe margin. Nevertheless, looking at the forecast, and considering the general sea state we encountered voyaging to Castle Bay, which was going to be pretty representative of the sea conditions we would face for at least the first 200nm of the crossing, i.e. light winds but with a residual head sea swell of 1.5m, we reflected on the fact that this did have a somewhat detrimental effect on our speed and range during the first leg. The most uncertain element, however, was the likely sea state we would face for the final 200nm, where freshening winds were forecast. Running out of fuel would obviously have been disastrous, so to be absolutely safe, I put 8,500 litres of fuel in her, even though at this weight she would likely struggle with speed initially. It turned out to be the right decision. As we departed Castle Bay, running through the calm waters around the islands we were able to run at 30 knots with the engine load at just over 80%, which was pretty impressive. However, once we had cleared the bay’s shelter and pushed out into the North Atlantic, we started running into the head sea swell. Punching into the swell and keeping the speed up over 30 knots meant the engine loads were reaching 90%, so I made the decision to reduce speed down to 20 knots, at which speed the load was just 70%, and run for a couple of hours at this reduced speed just to cover distance and burn off fuel, lightening our load to the point where we could get back up on the foil again without overstressing the engines, as they were going to have to look after us for a few thousand miles as we journeyed to our final destination. After a couple of hours, the seas calmed down a bit and our load lightened, and we were once again able to run at over 30 knots.

- Passing The Bull Rock on the West Coast of Ireland voyaging from Cork to Killybegs

- The first refuelling stop for Thunder Child II at Castle Bay in the Outer Hebrides

- Heading out 560nm across the North Atlantic to the coast of Iceland.

On the nose

Thunder Child II stopped by St Kilda, an archipelago in the North Atlantic, the last landfall before Iceland.

Our path took us very close to the islands of St Kilda. This is a place I had always wanted to visit, as over the years Safehaven Marine have built a few passenger craft that run from the Outer Hebrides islands to St Kilda. It was only a short detour adding a few miles from the most direct path, so it was worth losing a little bit of time to pass close by, where we stopped briefly to check the engine rooms and at the same time fly our drone, capturing some lovely footage of Thunder Child as she passed by the archipelago, which was pretty wild and foreboding in the mist that was present on the day we passed.

We continued onwards and conditions improved to near perfect, with a mirror-like sea – surely a rare occurrence in the North Atlantic, but it made for a very enjoyable and comfortable few hours as we travelled north. Around 200nm from Iceland, almost exactly as predicted by the Windy forecasting app, which proved incredibly accurate throughout the voyage, the wind got up, shifting to the south-west and freshening. As we moved into the night, the wind and seas increased and it became quite dirty – by no means rough, but when you’re running at over 30 knots, a 1.5–2 m head sea is tiring for such a long duration, no matter what boat you’re in, and we got beaten up a bit. Thankfully, at this latitude it never became truly dark, pretty much remaining like dusk, which when travelling at over 30 knots makes for a less stressful passage. Even though out in the middle of the North Atlantic there’s not much to hit, it’s still better to be able to see ahead, rather than be relying solely on our radars and FLIR camera. We also started to burn more fuel than expected in keeping up the speed in these conditions. This led to an anxious few hours during the night when we became a bit concerned as to whether we would make it if we maintained this speed, as range was becoming tight by our continuing fuel burn calculations. Thankfully, as morning came, conditions moderated, and we were able to run at around 38 knots for the remaining miles to the island of Vestmannaeyjabaer, which would be our final refuelling stop before crossing the finish line in Reykjavik.

- Heimaey island and city at Vestmannaeyjar archipelago. © HomoCosmicos

- Leaving Vestmannaeyjabaer through its spectacular entrance after refuelling heading for the finish line in Reykjavik

- The largest iceberg encountered in the Denmark Strait, of a beautiful shape and colour, 30m high

Across the line!

The crew toasting with a glass of Jameson’s whiskey cooled by ice from an iceberg

We arrived at Vestmannaeyjabaer around 5.30am the next morning. This island has the most spectacular and intimidating harbour entrance I have seen. The entrance lies between steep, sheer cliffs and is very narrow, and I could only imagine how dangerous it must be for the many fishing boats that operate out of the harbour when returning to port to seek shelter during a storm. Once again, our refuelling stop was efficient, with my friend Óskar Hafnfjörð Auðunsson of Trefjar boatyard in Iceland arranging for refuelling there; it’s always a relief when you see the tanker on the pier waiting for you, and you know it’s all going to be straightforward and easy. By now, all the crew were pretty tired. Some had managed to get some sleep, but on a fast boat travelling at speed in a bit of a seaway, albeit relatively slight, sleep is difficult at best, and all you can really hope for are power naps; however, amazingly, this is all you need to keep going. I myself at this stage hadn’t really slept for two days, running on stress and adrenaline, and was pretty exhausted. While refuelling, we again had a chance to fly our drone, and Carl captured some cool video as we departed Vestmannaeyjabaer with its spectacular cliffs in the background.

The final leg of our record run was some 130nm from Vestmannaeyjabaer to Reykjavik. For the first half of this leg, as we headed west, it was again pretty tough going, as with no worries about range now we were running Thunder Child pretty hard at up to 40 knots as we rounded the southern edge of Iceland before turning east to run across Reykjavik Bay towards the finish line. Luckily, Thunder Child is fitted with military-spec shock mitigation seating by SHOXS, which certainly helps with endurance. We crossed the finish line at Reykjavik at 50 knots with Oskar there as the official timekeeper for UIM, setting a time of just under 32 hours to cover the 866nm we had travelled from Killybegs in Ireland to Iceland, with an average speed underway of just over 30 knots. Crossing the finish line was a fabulous and memorable moment for all the crew – although it had been tough at times, all that was forgotten with the sense of achievement we experienced following our endeavours. During the record run we pushed the boat pretty hard at times, but she never let us down and her Cat engines never missed a beat. One does need a special boat to do such a long-distance relatively high-speed open ocean voyage, but she was designed especially for this.

Aerial panorama of downtown Reykjavik at sunset with colorful houses and snowy mountains in the background

Reykjavik gained

Once berthed in Reykjavik Marina, we were visited by customs and immigration officers. Apparently we had broken every rule in the book and should have cleared customs in Vestmannaeyjabaer. Mistakenly we assumed that as we were not departing the boat, only refuelling, it was not necessary there and that customs clearance would be at our main destination of Reykjavik, but we were wrong. The customs officers were, however, very accommodating, allowing us to officially clear customs there. Although all the crew had been fully vaccinated, we were still a bit apprehensive about immigration, but after the immigration officer had checked our COVID vaccination certificates we were deemed free to enter Iceland and leave the boat. This was a relief as the thought of having to stay aboard during quarantine was pretty unappealing. Being able to go ashore for a meal and a beer in Reykjavik was wonderful.

Iceland had lifted all COVID restrictions just days before, so it was great to be able to go to a restaurant and not have to wear a mask, something we had not been able to do in Ireland for almost 12 months.

After a good check over of the boat that evening and a good night’s rest aboard, we departed for Isafjordur in north -western Iceland to begin the next stage of our voyage, which was to cross the Arctic Circle in Thunder Child II and see an iceberg. Before leaving, we spoke with the local whale-watching guides who operate out of Reykjavik taking sightseers out into Reykjavik Bay to see whales. Helpfully they shared with us the best spots in the bay to see them as Carl was keen to get some drone footage of a humpback whale, and we were all excited about seeing one too.

West coast whales

Weather conditions were perfect as we departed and headed out to the bay, and sure enough, we were soon treated to the sight of minke whales and later a solitary humpback whale, with Carl capturing some cool drone footage. We had a very enjoyable voyage up the west coast of Iceland with calm seas and slack winds, stopping regularly to enjoy the scenery along the coast, which was truly spectacular with mountains and black volcanic rock formations, the like of which we had not seen along any other coastline. As we voyaged along the northern part of Iceland, we ran into fog that was pretty thick. Although not bad enough to slow us down, we were slightly concerned about entering the unfamiliar fjord and port of Isafjordur in thick fog. Miraculously, as we turned into the fjord the fog began to lift, and out of the fog the tops of the mountains that ran right down to the shore began to appear. As we entered the fjord, the fog completely cleared and we were treated to spectacular scenery as we entered Isafjordur – a small town with a population of some 2,600 situated between two tall mountains to the north and south. Here again, our friend Oskar had arranged for berthing and refuelling for us with the help of his niece who lives there. After refuelling, we headed into the small town and had a nice meal there before retuning aboard to turn in early and catch a bit of sleep, as we would be waking early to head off on what for me was to be the most exciting part of our voyage. We cast off the lines at 5am the next morning, departing Isafjordur to head for the Blosseville Coast of East Greenland.

Sea of ice

The drone piloted by Carl Randalls was invaluable for recording the spectacular moments during the voyage.

This part of our voyage was undoubtedly the most challenging, as at this time of the year the sea ice had not cleared completely off the east coast of Greenland. I had been studying the sea ice charts and satellite images of the region for weeks beforehand and had observed that the ice concentration was retreating and thinning but could see that sea ice still extended off the coast. Its concentration ranged from 1 to 3 on the EGG ice concentration scale, but still even this level was likely going to be too much for Thunder Child to attempt to navigate through with her FRP hull and exposed surface drive props. However, there was a break in the sea ice between Scoresby Sund and Kap Barclay that extended right up to the Blosseville Coast. The difficulties were firstly translating the actual coordinates of the sea ice edge from the ice chart into a waypoint on our plotter, and secondly taking into consideration the fact that the most recent ice chart was three days old. To reach this break in the sea ice we would have to travel north for some 100nm and then turn west and head for the coast. This seemed a reasonable and achievable plan at the time, however things would conspire against us.

Knowing that there would be no possible chance of refuelling in Greenland as the Blosseville Coast is completely uninhabited, we took on a full fuel load, enough for us to make the Greenland coast and return, a voyage of some 450nm. We left the fjords at Isafjordur and headed out into the Denmark Strait in calm seas with a long sea swell on our beam. After a couple of hours, we ran into the first bank of sea fog, which is pretty prevalent in the Denmark Strait at this time of year, so we were expecting it. We continued on running north at our most economical speed of around 30 knots, faster than was ideal in the conditions. But with all eyes vigilantly peering ahead and a close watch on our two radars, one set at long range and the other at short range, we made good, albeit stressful progress towards the point on our plotter where the sea ice edge was predicted to be. As none of us had ever navigated in these waters, we really didn’t know what to expect regarding icebergs, and at what point out into the Denmark Strait from Iceland we would encounter them, so we all watched the radar and seas ahead with bated breath for our first encounter.

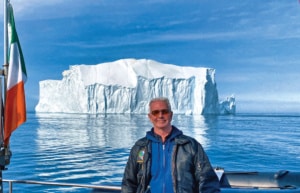

Around 70 miles from the Greenland Coast, we crossed the Arctic Circle. Suddenly the fog cleared – it had been patchy mostly, but this was the first real clearing with good visibility. The temperature also suddenly dropped – it had been around 8 degrees Celsius as we departed the Iceland coast but in a very short period of time it dropped to just 2 degrees; we guessed that this was because we had run into the Arctic Current. On the long-range radar we began to see targets appear, and from around 12 miles we got our first sight of an iceberg, to much excitement aboard. As we headed towards the target, we realised that it was a massive flat piece of what must have once been the ice pack. It was about a quarter of a mile long, much the same wide and about 3m high above the water. It was simply awesome to see and so completely alien to us. Needless to say, Carl immediately launched the drone and flew overhead as we circled the iceberg, capturing some amazing footage that showed the scale of the iceberg making Thunder Child II look insignificant in size by comparison. We later discovered that this was most likely carved from the Citronen Fjord, which is best known for producing such large square icebergs.

As we studied the radar, we could see that there was another fairly large target showing around 12 miles away that we could actually see quite clearly on the horizon. We figured that this would have to be a pretty big iceberg to be seen from such a distance, so we immediately headed in its direction. As we came closer, we could see that it was indeed a huge iceberg – we guessed about 30m high – with the classic jagged shape and wonderfully white-blue in colour. This presented us with the perfect opportunity to break out the bottle of Jameson whisky we had bought from Ireland and toast our voyage with a glass cooled by a piece of ice from an iceberg. We fished a small piece of ice from the sea that was floating around the large iceberg with our landing net and proceeded to break it up for our toast.

Fog bound

Frank Kowalski

We then continued on our route north heading for where we expected the edge of the sea ice to be. As we neared the vicinity, we hit very thick fog, pretty much pea soup with less than 50m visibility, which is in effect zero visibility. This forced us to slow right down to 10 knots as we knew that we were in close proximity to the sea ice pack edge, and one would need to be travelling slowly at this speed in order to have time to alter course for a growler that might appear suddenly ahead of us out of the fog. We always anticipated that our encounter with the sea ice would be fraught with danger, however we had not factored in combining that moment with heavy fog, which made it doubly dangerous and pretty stressful. We had figured that when we encountered the ice edge, we would be able to skirt round it to find the break in it that would allow us to reach the Blosseville Coast. This plan, of course, depended on good visibility to see far ahead and not be in zero visibility, which was the case at that moment. Sure enough, eventually we ran into the edge of the sea ice finger that was predicted by the ice chart to be extending off the coast.

It must be said that there was absolutely no way we could enter the ice pack, even though by my estimation it was only between 1 and 2 according to the density scale on the EGG chart. Without being able to see far ahead to try and pick a course through it, it was simply a non-starter, as it would not be possible to turn Thunder Child quickly enough to avoid the small pieces that could damage a prop, let alone the larger growlers, and impacts with smaller pieces of ice would be inevitable. So we decided to head north again, shadowing our past track on the plotter to clear water running at slow speed. As we continued, ahead of us, out of the fog, a large iceberg appeared; it had intermittently shown up on our radar, but nowhere near the size that it turned out to be.

This is one of the problems with relying on radar to spot icebergs, as depending on their shape, they can have a low RCS and a correspondingly small radar signature. Growlers would often not show up to any significant degree. This was a pretty spectacular iceberg – shrouded in fog, it was ghostly in appearance and the encounter was quite eerie. Such was the moment that we had to fly the drone to try and record it for posterity; however, after a short time flying, the drone malfunctioned and froze, hovering around 3m above the water. I pretty much wrote the drone off, but Carl insisted on us trying to recover it by backing the boat down, so that the aft deck was under the drone, and scooping the drone out of the air. Miraculously we were successful in this and saved the drone and, almost as importantly, the wonderful footage it had recorded. The cold and the fog may possibly have caused the malfunction.

- Large icebergs eerily shrouded in fog appears ahead of Thunder Child II.

- One can clearly see how much of the iceberg is invisible under the water.

- One of many icebergs encountered as the crew returned from attempting to reach the coast of Greenland as they travelled back across the Denmark Strait to Iceland

After this, we had to make a decision as to whether to continue trying to reach the coast or not. We had to factor in a few things: firstly, the danger from trying to continue to do so in the fog; secondly, the likelihood that the fog continued right up to the coast, and after spending what would be several hours at slow speed reaching the coast, we would not actually be able to see the coast upon arrival, which would be hugely disappointing; and lastly, we were burning up fuel in our endeavours and we had to be very mindful of our ultimate range capability to make it back to Isafjordur. In the end, we made the sensible decision to abandon the attempt to reach the Greenland Coast and head back to Iceland. On the way we were lucky enough to encounter several other fabulously shaped large icebergs on our course; the fog cleared and the sun came out and it was one of the most magical sea voyages I have ever made.

What I thought was really interesting, though, was the disorientation in terms of distance one could experience. The edge of the fog banks in the distance created what was like a false horizon, where it appeared as a white band above the sea forming a second horizon, which was most disorientating. At one point, there was a disagreement over how far away from us an iceberg was. To me, it looked like a small piece of ice maybe 300–400 m away, when it was in fact a pretty large iceberg 10 miles away from us, which only became believable to me as we motored towards it and it did not get any bigger. This iceberg was one of the most beautiful we encountered, being totally blue in colour. It was an upside-down iceberg that had capsized.

About turn

Cork, Ireland ©JoeDunckley

On the journey back to the coast of Iceland and Isafjordur we enjoyed wonderful calm seas, little fog and thankfully a midnight sun at this latitude, and at this time of year it never got dark – rather like a dull day at home – which made arriving back in Isafjordur at 2.30am an easy task in daylight compared to returning at night. So although we hadn’t quite made it to Greenland (we actually got to some 30nm from the coast), it was a fabulous experience and we captured the most amazing photos and video of Thunder Child II floating, shimmering like a block of gold against the awesome backdrop of an iceberg. What a sight that was! The voyage described here and back to Reykjavik left Thunder Child II awaiting its return voyage to Ireland some 2,000nm away. In part two of this account, I shall relate how the goal of reaching Greenland came to be considered ‘unfinished business’ – business we were determined to address …

Thunder Child II’s capabilities

Let’s briefly discuss the capabilities of Thunder Child II in respect of speed and range. Powered by four Caterpillar C8.7 650hp engines with France Helices surface drives, the unique ‘Monocat’ hull form has a Hysucraft hydrofoil between the catamaran’s hull sections. The hydrofoil lifts the hull out of the water at speed, reducing drag and allowing for very fuel-efficient high-speed cruising, the caveat being that the boat must be travelling at 30 knots to sustain this. The ability to ‘get up on the foil’ is greatly dependent on the boat’s weight, or more specifically the fuel load carried. To ensure longevity and reliability from the engines, I only run the boat at a maximum engine load of 80%, i.e. the power needed to run at 33 knots with 7,000 litres of fuel. The engine load decreases to just 65% with a more normal 3,000 litres of fuel for this size of craft. The cut-off point for being able to achieve a 30-knot cruise in calm seas is 7,500 litres, which gives a theoretical safe range of 700nm factoring in an average fuel economy of 0.1nm per litre, which is very good for a 23m boat weighing around 25 tons light, and 32 tons loaded at speeds from 34 knots right up to 50 knots. However, as with any boat, the sea state can have a significant effect on range, and adverse weather can reduce it by as much as 20%. Hence, the latter has to be factored into one’s range calculation.

The Ocean and the Circle

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world’s oceans, with an area of about 106,460,000 km2 (41,100,000 sq. mi.). It covers approximately 20% of the earth’s surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the ‘Old World’ of Europe and Asia from the ‘New World’ of the Americas in the European perception of the world.

The Atlantic Ocean occupies an elongated, S-shaped basin extending longitudinally between Europe and Africa to the east, and the Americas to the west. As one component of the interconnected World Ocean, it is connected in the north to the Arctic Ocean, as well as to the Pacific Ocean in the south-west, the Indian Ocean in the south-east and the Southern Ocean in the south (other definitions describe the Atlantic as extending southward to Antarctica). The Atlantic Ocean is divided into two parts by the Equatorial Counter Current, with the North Atlantic Ocean and the South Atlantic Ocean at about 8° N.

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of the earth. It marks the northernmost point at which the centre of the noon sun is just visible on the December solstice and the southernmost point at which the centre of the midnight sun is just visible on the June solstice. The region north of this circle is known as the Arctic, and the zone just to the south is called the Northern Temperate Zone.

As seen from the Arctic, the sun is above the horizon for 24 continuous hours at least once per year (and therefore visible at midnight), and below the horizon for 24 continuous hours at least once per year (and therefore not visible at noon). This is also true in the Antarctic region, south of the equivalent Antarctic Circle.

The position of the Arctic Circle is not fixed and currently runs 66°33’48.8” north of the equator. Its latitude depends on the earth’s axial tilt, which fluctuates within a margin of more than 2° over a 41,000-year period, owing to tidal forces resulting from the orbit of the moon. Consequently, the Arctic Circle is currently drifting northwards (shrinking) at a speed of about 15 metres (49 feet) per year.