HMS gets the opportunity to undertake the very first test here in the UK of the much-anticipated Cox diesel outboard technology. The twin 300hp installation, rigged to an Axopar 37 XC, certainly reveals some striking data, but what’s the true thinking behind the engine’s 160-million-pound research and development programme?

We find out …

With a sleek elegant design these outboards look as classy as any petrol alternative. Above. Twin 300hp Diesel setup on the Axopar 37 Cross Cabin (XC) test boat.

Here in the UK, HM Government have stated that their policy is to ban the use of petrol and diesel cars by the year 2030. The deadline, therefore, is just nine years from now. How will this affect the use of fossil fuels in the marine world? Well, as yet, we can’t tell for sure, but the strong likelihood is that the ban will include fossil fuel combustion engine technology in the marine sector too, and legislation, as reported in Issue 168 of PBR, is in fact already at work under the 2021 IMO Tier 3 Emissions Charter. This legislation’s purpose is to ban the commercial use of diesel-powered craft throughout a great swathe of European waters, including the North Sea and Baltic regions as well as most of the US.

Being invited to test the newly launched and much-anticipated 300hp Cox diesel outboard, therefore, might seem a proposition at odds with the fast-moving scheme of things. Indeed, the question could be posed: ‘Are we not testing a product here that is, from a viability standpoint, already history – one, in effect, already out of date?’

Investment and return

I had the opportunity to put the question of diesel viability, the IMO Tier 3 and gnarly issues involving the 2030 emissions deadline to Cox’s EMEA Sales Coordinator, Pedro Almeida, on the day of our outboard test. I specifically wanted to know how those entities responsible for injecting the astonishing figure of 160 million pounds sterling into the research and development of the Cox engine felt about the capital investment they’d made – bearing in mind these investors and bank rollers potentially had just nine years not only to see their investments repaid, but also, no doubt, for their intention of a profit to be realised. In response to my question, Almeida, looking somewhat circumspect and squinting his eyes, replied: ‘I don’t think they’re nervous …’

Almeida went on to state that he thought the Cox technology would remain viable ‘until electric battery power takes over’. We both agreed that the latter had a very long way to go before it could even begin to be considered a viable option for seagoing, planing, offshore-orientated vessels. And while battery power in the automotive world may be making significant strides, when you’re talking marine, it’s a whole different ball game. Boats, by their nature, are far less efficient objects, and as a result, compared to their road-going counterparts, it requires a whole lot more power/energy to propel them.

Alternative issues

While nine years may seem, on the one hand, to be a long way off, there are a multitude of questions still to be resolved regarding e-power before it can be truly considered a viable option. Let’s face it, it’s not so much the motors themselves that represent the stumbling block here, but rather the marine battery systems that power them. At this present time, battery technology is a long way from achieving the necessary performance demanded by most seagoing planing hulls. Conundrums surrounding weight, energy burn, cruising range, true marinisation, and the critical matter of recycling and sustainability are real issues that remain unresolved.

In light of the huge advancements yet to be made, it could be the case that marine battery technology simply isn’t achievable within the next nine years. This will mean that the likes of Cox and their competitor, Oxe, may just be extended legislative leniency. No doubt those who have invested so heavily in outboard diesel power would welcome that, but as Almeida indicated, such an outcome can’t be guaranteed.

The ‘what if?’

The ‘what if?’

In terms of the long-term viability of Cox, and in light of the challenges ahead, I also wanted to understand whether the Cox engine technology could be adapted to run on substances other than standard diesel oil. Almeida responded positively, and this time with confidence in his expression. ‘As you may know,’ he explained, ‘Cox’s development originally began life as a 2-stroke piston engine. However, we then changed direction and, as you see today, we eventually settled on the benefits that the conventional 4-stroke has to offer. This technology means that with some further development and modifications – the recalibrating of the ECU, for instance – it would be quite feasible for the Cox motor to run on synthetic diesel, plant-based fuels and potentially even hydrogen. Cox have a strong automotive heritage, so as a company we have the expertise already.’

This response now sounded more forward-thinking, and if such is the case, even in the worst outcome, an engine technology with the ability to utilise/run on alternative fuels could potentially provide Cox and their investors with the long-term solution they may well come to seek. That said, in order to convincingly develop these hybrid resolves, it’s not unreasonable to assume that even more cash will be required to adjust and modify the Cox system to enable it to run on these types of ‘alternative’ fuels.

Buy with the eye

But what of the Cox 300’s performance and, importantly too, its aesthetics and ‘eye appeal’? Starting with the latter, I can state, without any reservation, that the appearance of these motors is superb. They rival any of the big 4-strokes in terms of their styling and design. It’s clear that the Cox design team have given great thought to this matter, and in my view they look exciting, modern and purposeful. I would go as far as to say that if their work had been lacking in this area, it could have placed the commercial viability of the Cox in jeopardy. It is noteworthy too – and this is something that becomes apparent when driving the likes of the Axopar 37 test craft – that their COG is commendably low. They neither look too tall or top-heavy on the transom, nor drive as if they are. These 300hp engines individually weigh 390 kilos, and for the purposes of our test boat featured 25-inch legs.

At the helm of the 37 XC

Performance and handling

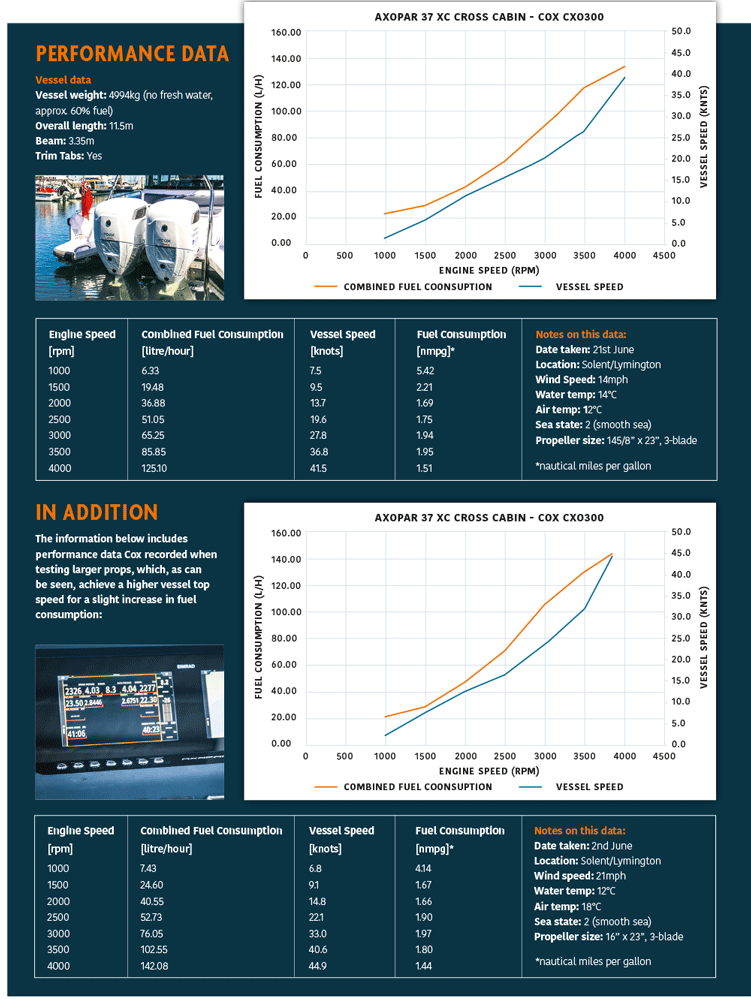

Now of course, the engine performance figures, and related data highlighted in the article’s information sections, speak for themselves. No doubt you’ll spot right away the critical fuel consumption test data. But let me add that in terms of the user experience at least, the differences between a Cox and an equivalent 4-stroke outboard are minimal – in fact, barely noticeable. Whether it be engine noise, vibration, power delivery and acceleration or top-end speed, the Cox throws up no unwelcome surprises and only seeks to please. (The test boat for some reason had had its fuel pumps housed within the actual cabin. This made the functioning of the engines a little noisier than normal, and on future installations this, I’m assured, will be addressed).

Bearing in mind that the Axopar represents a fair old lump of GRP and the fact that we were housed within a full cabin, which to a large extent diffuses true ‘ground effect’ performance, it remained very evident that these twin Cox outboards had no difficulty ensuring the boat picked up her skirts and delivered a sprightly turn of speed. In addition, low-end torque and essential ‘grunt’ were neither lacking nor any less impressive than one would expect from a diesel-engineered motor. But when you consider the fact that, even at absolute full throttle, these 300hp engines are burning in the region of two-thirds the amount of fuel that their 4-stroke petrol outboard contemporaries would be burning, well, you just can’t fail to be impressed.

Markets and benefits

Do I have any criticism to make concerning either the Cox 300’s design or its performance? No, I don’t. But it has to be said that any new technology can only be truly substantiated over time, and as for the degree to which the leisure market takes up this new alternative, we will just have to see … But the obvious benefits to those seeking to venture and cruise ‘off grid’, so to speak, to locations where dockside petrol is hard or impossible to come by, are strikingly obvious!

It’s also clear, when discussing such matters with Pedro Almeida, that Cox, though a British concern, have a global strategy, and the leisure market, the military, the performance-orientated commercial arena and the superyacht industry (where the latter, as in the case of the military and customs, favours a petrol-free scenario) are all markets where Cox intend to aim their blows. You might even be surprised to learn too that Cox have already started to attract interest from the North American bass fishing fraternity. These folks see the Cox’s ability to achieve greatly extended operational range, without the need for bigger tanks/increased fuel payload, as one that may well give them the winning edge over their Mercury 400hp and 600hp petrol-powered peers and competitors.

A word of caution being aired by Cox UK distributor Berthon, however, is the fact that boat builders and purchasers of this engine will need to ensure their transoms are validated to be rigged with his 393kg 479 lb.ft torque monster. Not all boats will qualify without modifications and possible new CE/UKCA ratifications being made.

Are there any other horsepower models in the Cox pipeline at this juncture? The answer is no. But there’s a whisper that at some point, besides this twin-rig configuration, PBR will be given the opportunity to test a single Cox 300hp on the back of an Axopar 28. If so, that will be an equally interesting prospect in my book. So, as and when the opportunity arises, we’ll bring you the results of such a test for sure. And with Cox promising a mere 12-week delivery time on the supply of all new engines, that opportunity may not be too long in the making!

300hp Mercury Verado 4-stroke comparative data

Comparative figures derived using an Axopar 37 Sun-Top model, which features an identical hull to the 37 XC but is approximately 300 kilos lighter than the XC model. The figures below were recorded by PBR, with the 37 Sun-Top test craft being rigged with twin 300hp Mercury Verado 4-stroke petrol engines. It’s clear that the further up the RPM spectrum one goes, the more the diesel outboard comes into its own, until the point where at wide open throttle, the Cox diesel is delivering a 33% efficiency saving over its Mercury petrol counterpart.

CXO300 Powertrain Specification

- Prop shaft power, kW (hp): 224 (300)

- Engine propping speed, rpm: 3700-4000

- Displacement, L (cu.in): 4.4 (266)

- Weight, kg (lb) : 393 (866)

- No of cylinders: 8

- Bore/stroke, mm (in): 84 (3.3)/98.5 (3.9)

- Compression ratio: 16:1

- Ratio 1 (prop speed): 1.23:1 (3259)

- Ratio 2 (prop speed): 1.46:1 (2739)

- Peak torque, Nm (lb.ft): 650 (479)

- Aspiration: Twin-turbo

- Shaft length, inch: 25” 30” 35”

- Emission compliance: EPA 3, IMO II, RCD II

- Start assist: Glow plugs

- Rating: Light duty commercial

- Trim range: -4• to +16•

- Tilt range: 71•

- Gear oil spec: SAE 80W90, API GL-5

- Powerhead oil spec: Fully synthetic API CI-4/

- SAE 10W40 or 5W40

- Propellor spine spec: 1.25” shaft / 19 tooth

- Colour options: Black/white

Contact

TEST VESSEL Axopar 37 Cross Cabin (XC)

This new 37 Crossover craft (37 XC) from Axopar is designed with all-weather boating in mind. That’s a very attractive proposition for UK boaters, who understand only too well the vagaries of the British climate. The all-weather solution that Axopar have created here reflects the fact that the Finns are true experts when it comes to engaging with the elements.

As can be witnessed at first glance, the 37 Crossover is designed and built with functionality in mind. Created very much with a view to adventure boating, the vessel’s semi-spartan, clean-cut, non-fussy modern styling is typically Scandinavian. But again, it’s clear, if we take the analogy of the automotive world, to what degree the UK and other UK consumers have taken to this design approach.

The 37, despite its fully enclosed cabin configuration, still provides ease of movement and a sense of spaciousness to both its outdoor and indoor social areas. Axopar themselves speak in terms of this craft having the versatility of an outboard, walk-around centre console. Likewise, and quite correctly in my view, they consider the 37 XC to be a true Gran Turismo of the seas. In fact, as is made plain in Axopar’s marketing literature, this model has been designed with the intention of opening a world of possibilities for safe, extended voyages in comfort, even in unpredictable weather. But despite such laudable aims, this would only be possible if the hull design genuinely delivered. It may come as no surprise to you that it genuinely does, and by all accounts it is a sea-kindly hull. Furthermore, despite its narrow, semi-wave-piercing-styled bow profile, the 37 XC’s hull has plenty of lift and forward buoyancy, which in our first-hand experience, and as was confirmed in the inclement conditions on the day of the test, means she recovers well in a following sea.

The innovative gullwing door concept adopted by Axopar cleverly and imaginatively opens up the front cabin in a very special way. Plus, the boat’s sociable foredeck, with its seating/table/sun deck flexibility, coupled to the versatility of its aft deck, ensures that the 37 XC never feels ‘overprotective’ or detached from the world outside the cabin glass. Indeed, on a fine day you can slide back the canvas roof and the two large sliding doors and let the sunshine fill the cabin interior.

The craft we tested featured a spacious forward cabin with a master double berth and huge degrees of storage with additional convertible berths within the main cabin. This particular boat featured neither a galley nor a heads/shower cubicle, which I found to be at odds with the 37 XC’s cruising and exploration ethos. But that said, it has been spec’d purely as a test craft for Cox, and Offshore Powerboats, the chief supplier of these craft on the south coast of England, assured me that such options/facilities are available and can be accommodated at the request of the client. The option on this model of an aft cabin with additional berthing can be chosen too.

The test day was downright murky, with constant driving rain. Even so, we remained warm and dry and fully able to enjoy our time on the water aboard a craft that was a pleasure to helm. From a driver’s perspective, the flight deck’s ergonomics are commendable, and as for the Simrad Glass Screen technology, it simply makes the helming and navigating of this craft an inspirational joy. With virtually 360 visibility at the wheel, a safe eye on one’s surroundings can be maintained without difficulty, and for crew or passengers, this attribute ensures that the sights along the way are never lost. On the day of the test, we also had the heater blowers aiming air directly at the forward-raked cabin windows. This ensured that no misting occurred, which I confess was a joy.

If I had one criticism to make, it would be the table set directly behind the helm seat. It was too large to stand behind comfortably as the space between it and the passenger seating astern of it meant that standing room, etc. was cramped.

But all in all, as could be expected from one of the world’s most successful exponents of offshore leisure boating, Axopar have a very fine model in their 37 XC – one that undoubtedly has the ability to appeal to a wide audience often with distinctly different aims and pursuits in mind.

Axopar 37 (XC) Cross Cabin specification

- Overall length (excl. engine): 11.50m (37ft 9in)

- Beam: 3.35m (11ft)

- Weight (excl. engine): 3770kg (8311lb)

- Passengers: B:10 / C:12

- Berths: 2 persons (with optional aft cabin 2+2)

- Fuel capacity: 730L (193 gal)

- Construction: GRP

- Hull: Twin-stepped 20-degree V sharp-entry hull

- Classification: B – Offshore, C – Coastal

- Max. speed range: 38–48 knots

Price

- 37 XC model without engines: £160,000 (inc. VAT)

- Single Cox 300hp engine: The 25” version starts at £38,950 (inc. VAT) and has a choice of rigging kit from £4,240.37 (+ VAT)

Other shaft length versions are available as well as single/twin/triple rigging kits c/w hydraulic steering, etc.