In this special PBR feature, HMS looks at the matter of ‘man overboard’ from a different perspective and gain the expert contribution of one of the RNLI’s senior trainers.

Taking emergency action and undertaking a successful search for a person who has fallen overboard is not a random process. On the contrary, it largely works to a formula of tried-and-trusted methods and protocols. Why so? Because the sea is neither a benign nor a static environment; it embodies forces that are constantly on the move. It also has the ability to summon a plethora of evils that often conspire to literally hide, or at least obscure, a casualty from even the keenest observer. And if that wasn’t enough, if you are unfortunate enough to become its victim, the sea’s temperature alone is sufficient to kill you. If you doubt this bleak appraisal of our fickle friend and how challenging it may be to locate an MOB casualty, then consider the following. One day you might need to call upon this knowledge.

Hide and seek

First off, let’s take the matter of light refraction. This phenomenon can mask the observer’s view of the water’s surface. The lower the object or subject is within the water, and the lower to the water’s surface the observer’s line of sight is, the greater the effect light refraction will have, especially when looking into the sun. Shimmering light on the water’s surface can be ‘blinding’, although this effect can be lessened hugely, or almost entirely filtered out, by the wearing of Polaroid sunglasses.

Fewer than a handful of men have ever been recorded as having actually walked on water. The apostle Peter tried it, of course, and for various reasons ended up getting very wet! But when a casualty enters the water, even when wearing a life jacket, they emerge with just their head showing and/or perhaps just a slither of their body on view above the water’s surface. By its nature, the sea obscures or hides approximately 90% of any body mass entering it.

Crew onboard the Hoylake Shannon class lifeboat Edmund Hawthorn Micklewood 13-06 during a man overboard (MOB) training exercise at sea. Throwline being thrown to person in water.

Besides failing light, weather conditions such as haze, fog and precipitation reduce the likelihood of a successful sighting hugely. Weather conditions can, of course, change at sea almost without warning too. Visibility issues caused by the natural elements likely represent the greatest set of challenges to anyone involved in a search-and-rescue scenario.

If the foregoing wasn’t bad enough, unlike the static nature of the land’s surface, the sea is complicated by waves! These do not have to be very large before they exceed the height of a casualty in the water. But if they are substantial in size, it could even reach the point where the casualty is being obscured completely for many seconds at a time. Add in the additional issue of flying spray in conditions typically exceeding force 7 in strength and you can well imagine how difficult a man overboard search truly becomes. In many instances, but only if the conditions allow for it, only a helicopter or a drone may have any realistic likelihood of sighting a casualty in the water. Whenever the circumstances allow, it stands to reason that the higher the vantage point, the less such things as light refraction and waves have the ability to obscure a person in the water. It makes good sense to carry a pair of binoculars on board your boat, not merely for nature watching, etc. but also to call upon in the event of requiring aid for the sighting of an MOB casualty. As not all MOBs take place in daylight, some form of powerful searchlight, even if this equates to a good-quality hand torch, should also be carried as part of your essential offshore kit.

Crew onboard the Llandudno Shannon class lifeboat William F Yates 13-18 during a man overboard (MOB) training exercise at sea. Crew member Phil Howell reaching down towards the camera, shot from waterline.

What we haven’t mentioned, of course, is the not inconsequential matter of tides. We covered this subject in some detail within Issue 180, but in no small measure, the ability for the sea to move the casualty away from his/her original entry/MOB point is, in every sense, an example of the sea playing to its own set of rules. If the tide is running at 1.5 knots, for instance, that clearly means a casualty will be carried away by the tide to a distance of almost 2 miles in just 60 minutes. In other words, there is no time to lose in an MOB rescue scenario. Quite literally, every minute counts. That said, because the tide’s direction and rate is something that can usually be determined and calculated quite accurately, it can also be an ally in determining a casualty’s position. But this ‘advantage’ requires accurate tidal prediction and an expert ability to process and use this information to the rescuer’s advantage. Besides which, tides are a complex phenomenon, and when their movement is affected by the variances of the coastline and its geological features, exactly where a tidal current might take a casualty will likely boil down to the application of intimate local knowledge. The lifeboatmen of old were absolute experts in this respect.

Crew onboard the Swanage Shannon class lifeboat George Thomas Lacy 13-13. Simulated rescue of a fisherman from the sea, shot for LEgacy DRTV advert 2022.

Prevention better than cure

The very best MOB scenario is to avoid it altogether! But accidents happen, and by its nature, the sea is an environment that heightens the risk of accidents occurring. So, what precautions can you take? Here’s a brief list of some of the things we all need to keep in mind.

1. Whenever aboard a vessel, particularly one that’s fast-moving, think before you move. Use grab holds and keep your CoG low, especially on a wet deck, by keeping your knees a little bent.

2. If you’re out in rough conditions, watch out for any item that may inadvertently strike you in the face, e.g. a seat back, the edge of the cabin roof, a bulkhead face, etc.

3. As a skipper, ALWAYS wear your kill cord when underway.

4. Be mindful too, as skipper, of those passengers positioned not directly in your line of sight. We are not suggesting that your private vessel should be fitted out this way, but commercial ‘Sea Safari’-styled operators tend to have their passenger seats located ahead of the helm station. This is to enable them to observe any potential issues instantaneously.

5. Wear the correct life jacket. This means an auto-inflate on all open craft and a manual inflate when on passage aboard a cabin craft in adverse weather. You can imagine, too, how valuable a light on your life jacket would be to those trying to find you in failing light or in the dark. Offshore yachtsmen’s jackets will often have this additional feature fitted as standard, and it doesn’t take much imagination to appreciate why.

6. PLBs have proved their life-saving capabilities time and again in recent years. These personal electronic devices are kept on one’s person and, as in the case of Ocean Safety’s latest product, are even designed to be attached to a life jacket. Just think how grateful, how relieved you would be if, upon unexpectedly becoming an MOB casualty, you could call upon the assistance of such a device. The few hundred pounds you’d expended on purchasing a GPS-enabled PLB would instantly feel like the best investment you’d ever made!

7. If you enjoy offshore adventuring, particularly aboard an open craft such as a RIB, then consider your attire in line with both the prevailing conditions and how far offshore you’ll be at any given time. If you want to be kept safe in all situations, regardless of weather and sea state, there really is only one option: a full drysuit. I speak from experience. It doesn’t matter how technically advanced any expensive foul-weather garment may be, no clothing of this type will save your life if you go into the water. If you boat offshore in an open craft or regularly undertake extended coastal voyages, there is no alternative to a good-quality, fully immersion-proof drysuit. It’s an item of clothing that will potentially buy you hours of life if you find yourself in an MOB situation.

8. Personal mini-flare packs tended to be carried by offshore adventurers, particularly before PLBs came to the fore. They may not be so readily carried these days in the pocket of a drysuit or sailing jacket, but they still have their place and have proved their worth countless times, both in the professional and offshore arenas. Their advantage is that they are inexpensive, but unlike a PLB or EPRIB, remember, flares of any description will only be effective in conditions where they can be seen.

9. A waterproof/water-resistant hand-held VHF, such as those produced by the radio manufacturer Icom, is immensely compact and rugged and is designed to attach to one’s person, usually the life jacket. Being able to call for assistance and then direct your rescuers to you gives you, without doubt, the most incredible advantage. If you haven’t already done so, why not think of investing in such an item with a view to keeping it attached to your life jacket?

Expert witness: search-and-rescue techniques

Adrian Bannister, one of the RNLI’s chief lifeboat crew trainers

But now onto the matter of our expert witness, and to help us in this respect, we’ve invited Adrian Bannister, one of the RNLI’s chief lifeboat crew trainers, to enlighten us as to the professional’s approach to MOB search and rescue. This reveals the techniques and methods employed by the RNLI, one of the most experienced and highly recognised life-saving operations in the world. Here, then, are Adrian’s top life-saving search-and-rescue recommendations.

1. The initial actions and the ability to keep calm under pressure play a big part in a successful outcome during an emergency. Aim to stabilise the situation; communicate using mini-briefs and closed-loop communication with the crew, repeating all verbal commands and actions throughout the task. In the event of a person overboard, advise crew and reduce speed. Point at, while keeping your eyes on, the position, and immediately mark it using a GPS waypoint, alongside a time.

2. If you have a person overboard, raise the alarm straight away by using any available means. If you recover the person from the water, the lifeboats can always be stood down, but they would prefer to be en route. Use your VHF DSC radio, if fitted, to send out a distress alert. It only takes five or six seconds and could save a life. Follow up your distress alert with a Mayday call on Channel 16. If there is one transmission you want your crew to be confident sending it’s the Mayday call.

3. If the person overboard is out of sight, after noting the position and time and sending your distress alert and Mayday call, it’s time to search. Prepare the boat and brief the crew. In darkness or restricted visibility and a flat sea, if safe to do so, I may turn the engine off and listen for shouting. Use torches and assign crewmembers a side to watch, be it port or starboard, looking out to the sides.

4. My initial intention is to run on a reciprocal course back down my track at a reduced speed. You could return back along your boat’s wash having looked at the ship’s compass for a reciprocal heading. In restricted visibility, you may need to use the breadcrumb trail/track on a chartplotter. If minimal time has elapsed, even when travelling at planing speed, the MOB is unlikely to be far along your track.

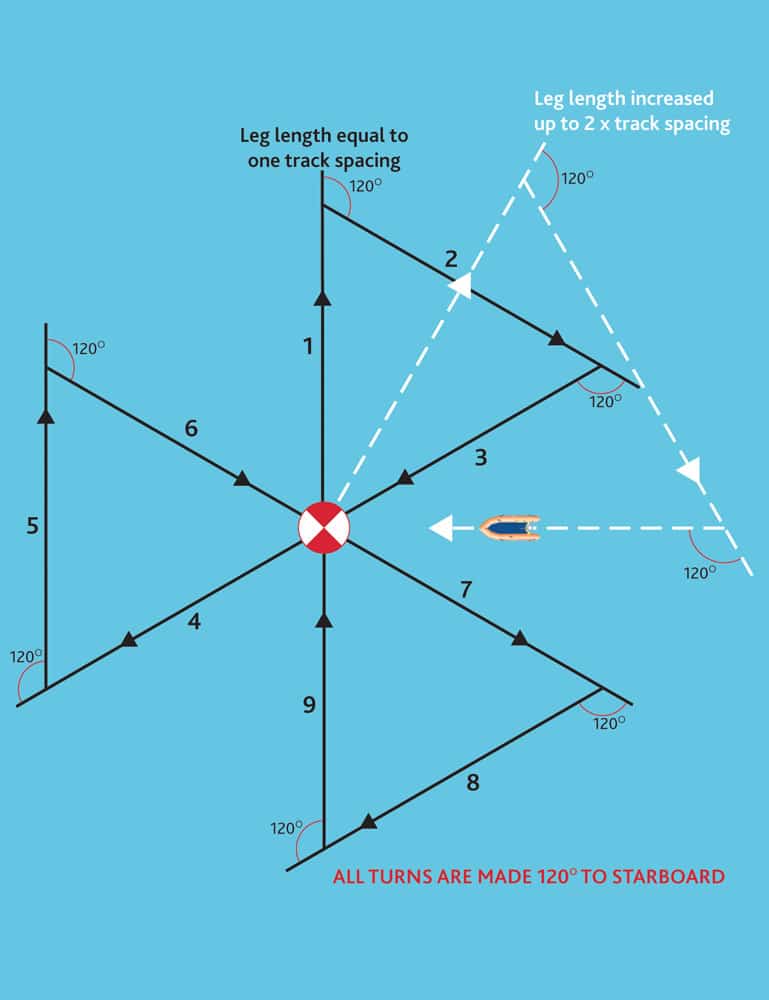

5. When arriving at the scene shortly after the incident, an RNLI helm or coxswain will opt to execute a datum/water-based search such as a sector search. They will deploy a hi-vis floating datum with a light at night and a coiled line or bucket attached to prevent it being blown away and use this as a reference point to return to each time. A sector search consists of 18 legs, with all course changes to starboard at 120 degrees. (See Sector Search graphic below)

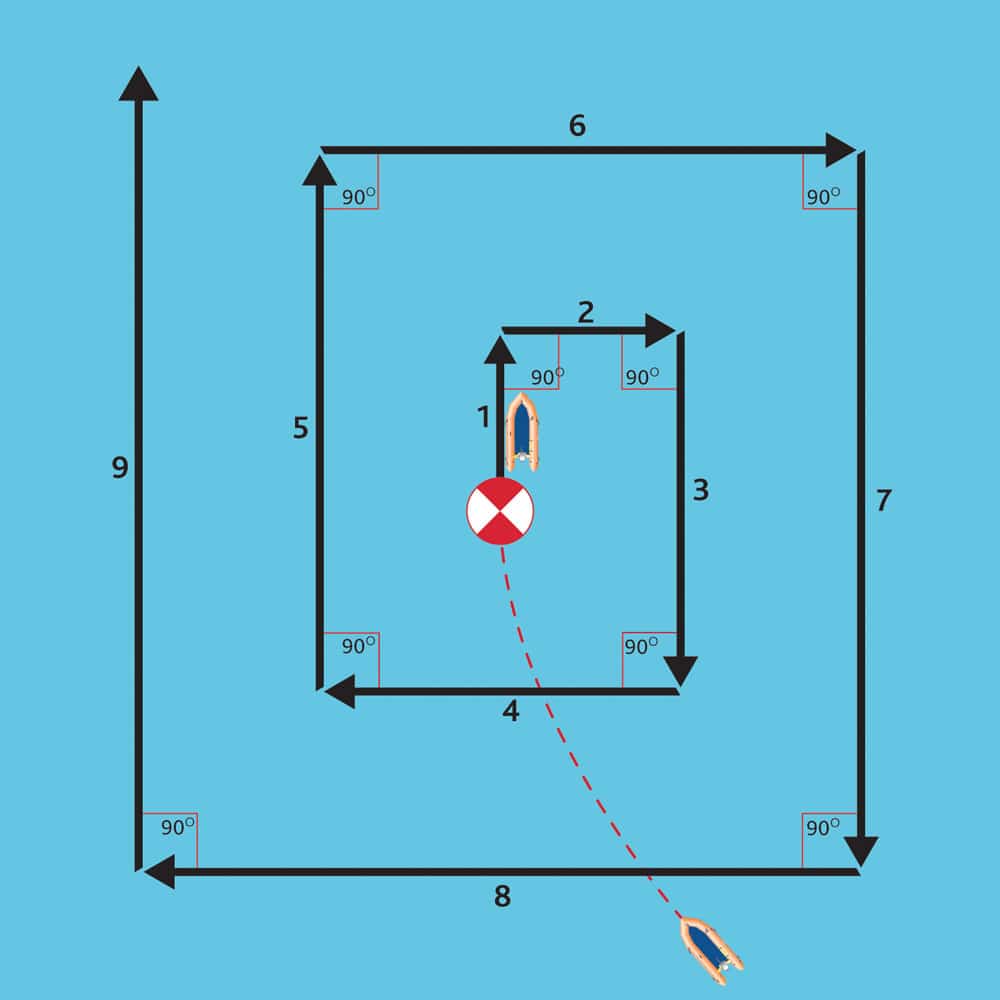

6. I would suggest you keep things simple by prepping an expanding square search for those not familiar with a sector search: select a comfortable, safe speed for the conditions (not so fast that you might miss seeing the person). All speeds are to be through the water using a Log or engine RPM. Once the speed is set, the throttles should not be adjusted at all, even for the turns, unless for the safety of the boat. Use a magnetic ship’s compass and the cardinal points N, E, S and W for your course; this will allow you to drift with the tide at the same rate as your person in the water. The legs will increase every other leg.

Expanding Square example

Leg 1: North 30 seconds

Leg 2: East 30 seconds

Leg 3: South 60 seconds

Leg 4: West 60 seconds

Leg 5: North 1 min 30 seconds

Leg 6: East 1 min 30 seconds

Leg 7: South 2 mins

Once the lifeboat is on scene, they will contact you via VHF and commence a search. At night, if the helicopter is not in the area, the lifeboat may position upwind and deploy white parachute rockets in order to illuminate a large area. Avoid looking at the rockets to maintain night vision; focus on the illuminated water. If you are able to assist the lifeboats in the search, they will then pass on further information.

Adrian Bannister – Lifeboat Crew Trainer

Crew onboard the Llandudno Shannon class lifeboat William F Yates 13-18 during a man overboard (MOB) training exercise at sea. Throwline being thrown to person in water.

Having grown up around water, sailing, canoeing, kayaking and powerboating in the Sea Cadets and Scouts, Adrian focused his efforts on making a career out of training. Before working at the RNLI, he taught a large number of RYA courses for all levels up to Instructor and Yachtmaster level. He’s now spent the last six years training RNLI lifeboat crews on both the Institute’s inshore and all-weather lifeboats.