- … the key is practice, so get out there in low wind conditions and go in and out of plenty of berths.

- When setting up to approach a pontoon, first assess the wind and tide, and then check you have depth and be aware of other craft.

- Whenever there’s any wind, understanding how your boat will react is key.

Paul Glatzel offers some extremely helpful tips on the potentially tricky aspect, at the end of a successful day, of ‘coming alongside’ …

You’ve had a long enjoyable day afloat, and all that awaits is getting back alongside the pontoon/your berth in the marina – how difficult can it be? As we all know, too often ‘coming alongside’ can be the most stressful part of the day, with the approach not going as smoothly as you wanted and maybe crosswords between those on board spoiling a great day.

In this article, we’ll have a look at some tricks and tips for making your ‘coming alongsides’ smoother and potentially safer. Before we look at the specifics of moving a boat alongside a pontoon, though, it’s important to be happy with some of the key aspects of how the boat handles.

Whenever there’s any wind, understanding how your boat will react is key. Any powerboat is only ‘happy’ when it is lying side on (‘beam on’) to the wind. Point the bow, or the stern, into the wind and wait a little bit and the boat will rotate to lie beam on to the wind. With boats such as four-berth family cruisers or longer speedboats like long RIBs, the speed at which the boat comes round to lie beam on can be a matter of seconds due to their light bows and relatively heavy sterns. Understanding how quickly your own boat will react in a variety of wind strengths is key if you are to be able to predict what it will do in close-quarter situations and thus react accordingly and be able to fully control its movement.

To manage the movement of the bow, you’ll need to be able to read the conditions and then control the boat using a technique instructors refer to as ‘steer then gear’. Basically, what we mean by this is that if you want to turn the bow to starboard (to the right), we steer first towards where we want the bow to go, then engage gear. By having the steering turned before engaging gear, the reaction of the bow will be immediate. Contrast this with a situation where you want to go right but the steering is to the left when you engage gear. The bow will immediately go left as you then rapidly turn right – the turn will take longer and eat up more space. There are times when ‘gear then steer’ may be good too, so understanding and practicing each is time well spent.

To manoeuvre a boat in a marina, you’ll need to be able to turn the boat effectively. The key to doing this well is to embrace the ‘steer then gear’ concept as already outlined.

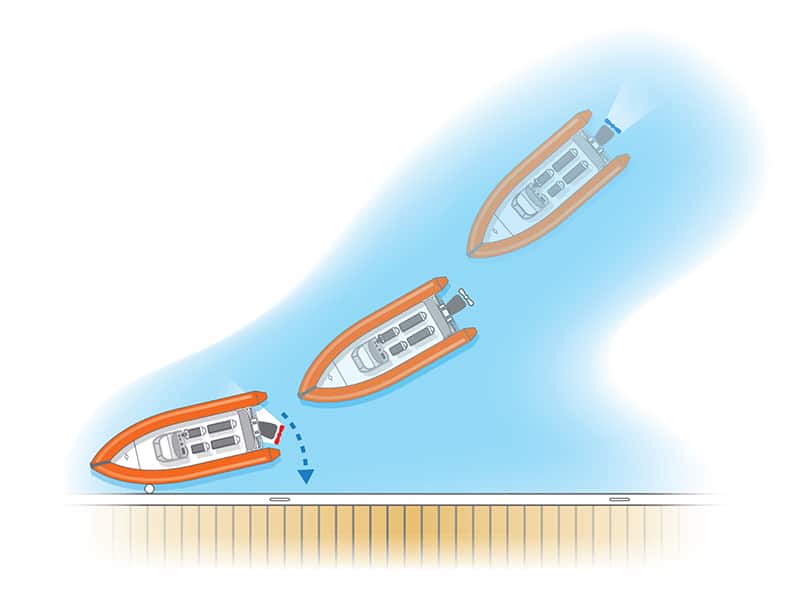

To come pretty much to a stop (no. 1), ideally turn into the wind (as getting the wind to help the bow round can make it easier), go into gear and then into neutral. Make sure that you only stay in gear for a second or so. If need be, do it again until you have turned through about 90°. By only spending a second or so in gear rather than much longer, you keep the turn tighter space-wise, otherwise you risk building too much momentum and thus eating up space. In neutral, turn the other way, then into and out of reverse gear (no. 2), then in neutral turn again and into forward once more to complete the turn (no. 3). It’s well worth practicing this move a lot, as once you have it mastered it’s the key to being really competent in close-quarter situations.

When setting up to approach a pontoon, first assess the wind and tide, and then check you have depth and be aware of other craft. Ideally plan an approach to head into the elements; however, in a marina you’ll often just have to deal with what you face.

Start a good distance off the pontoon, then approach, ideally at an angle of roughly 30°, and moderate your forward speed using into/out of gear. Have in mind where you want to come alongside the pontoon and target a point 1m off it. Be positive towards that point, and at the target point turn towards the pontoon quickly, then into/out of reverse gear. Do it a couple of times and the forward momentum is arrested and you should slide sideways gently onto the berth. Again, like any aspect of manoeuvring, it’s a question of practice, practice and more practice. Do it 20‒30 times and you will move from having to think about it to doing it from ‘muscle memory’.

So what about finger berths in a marina? Let’s take this marina as an example and look at how we deal with the various berths.

Berth A: You are turning up into the wind and momentum is onto the berth. Here a slow steady approach will work.

Berth B: Approaching from the left, the berth is a ‘closed’-face berth. Generally going past, turning, then approaching with momentum onto the berth will be the best move – by going past and turning the berth has become ‘open faced’.

Berth C: This is much like Berth B but the approach is to reverse in. Powerboats generally handle stern to wind very well, so once in position, a slow steady approach will work well.

Berth D: Again, getting past the berth and turning to give momentum onto the berth makes sense. However, the challenge with this berth is the risk of going in too fast with the wind pushing you in. Get lined up and the wind should do the rest.

Berth E: This can be the most challenging berth as the wind will try to push the bow off to the left or right. Position the stern of the craft near the finger and aim to reverse, making sure the bow stays pointing into the wind. Be prepared to abort if it’s going wrong. The sign of a good skipper will sometimes be deciding to approach the berth a different way – perhaps bow first – in challenging conditions.

Tip: We all want a coming alongside to be mm perfect, but be realistic. If you get alongside safely and it wasn’t the best one ever, no problem – as one client who had a little plane commented when they had come alongside safely but not prettily: ‘In our little plane every landing we survive is a good landing!’ How true!

As we’ve already said, the key is practice, so get out there in low wind conditions and go in and out of plenty of berths. Then do it again with a bit more wind. Practice enough and you’ll become the marina pro and really enjoy the challenge close-quarter handling presents.

Have fun!

| The RYA Powerboat Handbook is available for £16.99 from the RYA shop. It is also available as an e-book using the RYA app. |

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and examiner and is based in Poole in Dorset. He runs Powerboat Training UK and is the author of the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook.