Whatever your engine set-up, pushing the throttle forward and accelerating over glassy seas always feels great. Paul Glatzel reports on the additional challenges and responsibility for the skipper that come with ‘going fast’.

In this article we’ll look at the factors to consider when driving at higher speeds and what to do to make sure that you, your family and others afloat are safe.

Driving at any speed can lead to a driver falling or being ejected from the vessel, so it is imperative that the person driving wears the kill cord. This should be worn around the thigh. Stretched, frayed or UV-damaged kill cords should always be replaced, and manufacturers’ own products are recommended as replacements as they are guaranteed to fit properly and so always work when needed. Carrying a spare kill cord that is easily available to other crew on board makes real sense too.

Before going faster there is a need to ensure that the boat is set up for operating at higher speeds. Make sure that items in lockers and seat pods are secured, as even hitting smaller waves at higher speeds can throw things around. This is particularly so at the bow, where the vertical movement is greater. Anchors in bow lockers need to be tied down or else they risk, over time, punching through the hull. Padding the locker with foam or rubber matting can also protect the hull from longer-term damage.

The other items that you need to protect from damage are, of course, people!

Trimming

The impacts that can be transmitted through the hull to those on board can be considerable, but there is much that can be done to mitigate these effects. Firstly, make sure that the people that travel with you are aware that there can be significant impacts, and that expectant mums and those with joint, knee or back issues think again before committing to coming afloat. Where you place people in the boat is key too, and the bow area should be considered out of bounds at higher speeds as there is a real risk of serious impact on those seated there, or even of someone being ejected from the vessel in some craft. Rear bench seats will be far less susceptible to vertical movement; however, there needs to be good lateral support or else the sideways forces may lead to a person being thrown out of the side of the boat.

Jockey seats in RIBs can work well, as a standing position with ankles, knees and hips bent acts as a natural shock absorber. Be careful, though, to ensure that feet are planted firmly and equally on level decks so that the shocks are taken equally, as much as is possible, through each leg. Think too about what you have on your feet, as footwear with some give (running shoes, hiking shoes/boots) may diminish the effect of impacts and reduce fatigue.

As skipper, ensure that you, or whoever is helming, drives with consideration for the person in the worst or least safe seating position. Remember that those driving have a throttle and steering wheel to hold onto and are better placed to predict approaching wave impacts, and are probably more experienced at being afloat too.

When driving faster, injuries often occur when a craft changes direction suddenly, so ensure that your progress is generally straight and try to eliminate rapid changes in direction.

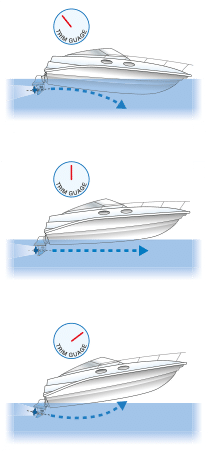

The other decision a skipper will need to make relates to trim. A craft can be trimmed ‘fore-aft’ (the bow can be raised or lowered) and ‘laterally’ (side to side). In smaller craft, invariably the fore-aft trim will be adjusted by altering the angle of the outboard(s) or outdrive legs. By default, these will usually be trimmed in (or ‘down’), but as the craft gets up onto the plane, if the conditions are right, then the bow can be trimmed up slightly. This allows the ‘wetted area’ to reduce and so improves efficiency and speed at the same rev level. All boats are slightly different, though, and a trim setting that works for one craft may not work for others, so always adjust trim and feel what works best.

Going into a turn at higher speeds requires real care as there is a danger that the rear of the craft may skid on a tighter turn and then catch, with a dramatic change in the position of the craft – a ‘hook’. Such a dramatic movement can eject people from the craft and lead to serious injuries. Turns should generally be wide and slow with the bow trimmed down, although craft with a ‘stepped hull’ may need to remain slightly trimmed up on a turn to prevent the ‘step’ engaging and hooking the craft. Consult the manufacturer for vessel-specific handling advice.

As your speed increases, items in the water such as lobster pot markers, lumps of wood, waves or wash from another vessel come towards you far more quickly. The skipper helming needs to mix looking well into the distance with watching for issues far closer to the boat. If it becomes difficult to pick out things at speed, then slow down, as you need to be able to see and react to what is ahead of you.

Going fast is, of course, great fun, but you need to match your speed to the sea conditions that you come across. Flat calm seas may allow you to open the throttles up almost fully, but as conditions get rougher or there are more waves around from other craft, you will need to consider a speed that best matches the conditions.

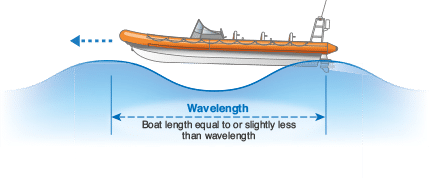

Wavelength

The manner and speed that you drive at will be influenced by your direction of travel relative to the wind too. Heading upwind/‘up-sea’ will tend to mean driving into the steeper face of approaching waves. If these waves are small, increasing speed may allow you to drive from wave crest to wave crest, but as wave height increases, so the distance between waves increases, and at speed there is a risk of impacting hard into approaching waves.

With wind behind (a following sea/‘down-sea’), good progress can be made, but there is a real risk of driving the bow over a wave crest and into a ‘hole’ in front of the wave, and ‘stuffing’ the boat into the back of the next wave, with massive deceleration and a high chance of injury. This is called ‘stuffing’.

A beam sea (with wind on the side of the boat) may allow really good progress, and the passage may be smooth as you progress along wave troughs and gently over crests, but again real care will need to be taken to ensure that waves approaching from the upwind side don’t catch you out.

Handling a craft in more challenging and rougher conditions is an entire subject in itself, and it will almost always be the case that as it gets rougher you will need to reduce speed considerably. A vessel hitting waves at speed with the prop leaving the water looks great in photos and on video, but it is not usually the best way to make good progress, and the risk of significant injury to the people on board, not to mention damage to the craft, is far higher.

There is no doubt that driving faster is great fun, and almost all of us enjoy doing it. And if you appreciate and manage the risks, you will reduce the possible effects of an issue and keep people safe. Have fun afloat!

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK in Poole and Lymington (www.powerboattraininguk.co.uk) and is an advisor for the RNLI.

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK in Poole and Lymington (www.powerboattraininguk.co.uk) and is an advisor for the RNLI.