Paul Glatzel provides some essential guidance for those among us who sometimes find berthing more than a little tricky …

There cannot be any doubt that exploring along a deserted coastline, anchoring in a secluded bay, rafting up with friends or opening up the throttles across glassy seas is what we all love doing in boats. Equally, there can’t really be any doubt that if there is an area of stress for most boaters it’s ensuring that the return to the berth is a success and is achieved without clouting the boat alongside while retaining a semblance of dignity and good relations with those that you have gone boating with.

As you start out boating you will probably restrict your activity to pretty friendly conditions and possibly tend to leave from and return to the same location. However, as your experience and confidence grow, so too does the desire to explore further afield, and potentially more challenging conditions may arise. You therefore need to be able to enter/leave any berth and be capable of doing so when it’s blowing pretty strongly. Being able to do this safely and successfully comes from a mixture of understanding some of the key principles of boat handling and plenty of practice.

Before we look at some example situations, let’s remind ourselves of some key principles.

The wind quite obviously has a major impact on us in our powerboats. However, the impact is generally predictable, so by understanding what the wind wants to do to your boat we can harness these characteristics to our own benefit.

With these characteristics in mind, before we consider any manoeuvre in a marina we should consider this acronym:

APE – Assess, Plan, Execute

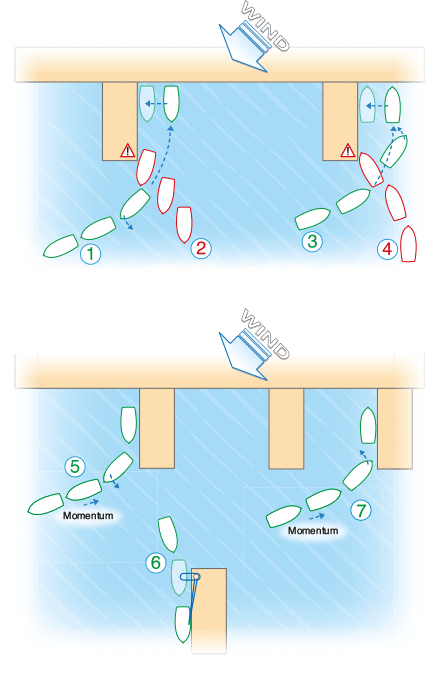

Looking at what the wind and stream are doing near the berth we are aiming for, the amount of space around the berth and any depth issues will allow us to start to predict how our craft will react to the elements present. We can then plan our approach.

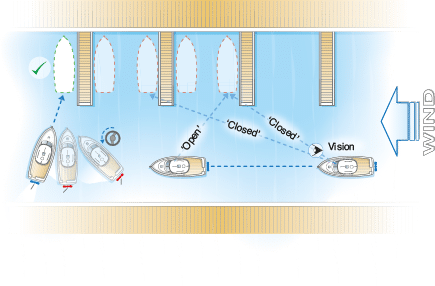

In our marina image we see the wind blowing from the north-east, but in a position where the craft are going to be pushed onto the berth. The challenge this creates can be seen with ‘Boat 2’, which is trying to reverse into the berth from a slightly upwind position. There’s a constant challenge for the skipper to harness the wind and ensure that it doesn’t start to take control of the craft; and for ‘Boat 2’ with a strong wind, unless the helmsman gets the craft into the berth, clearing the corner, there is a real danger of engaging with the pontoon. ‘Boat 1’ is reversing initially into the wind (a very stable position) and then turns the helm to starboard (to the right) to get into the berth. This creates upwind movement of the bow, which balances the wind force, creating (for a short while) a stable position, and allowing the helmsman to reverse into the berth.

‘Boat 4’ is faced with a slightly different issue, which is the boat’s desire to lie side on to the wind coupled to the desire of the wind to push the boat downwind. By arriving from a different start position to ‘Boat 3’, the helmsman is in full control before turning into the berth positively before the wind has time to start affecting the bow.

On many craft the ‘midships’ cleat is the most valuable cleat on the craft, yet it is often underused.

Here are some alternative examples:

In all of these examples we have ‘wind off’ the berth. By reversing towards the berth from a downwind position, ‘Boat 5’ retains good control before a well-timed turn flicks the bow upwind to allow the vessel to come alongside parallel to the berth for long enough to get lines on.

On many craft the ‘midships’ cleat is the most valuable cleat on the craft, yet it is often underused. ‘Boat 6’ is approaching the berth and risks being blown off due to strong winds. Getting a line on quickly is key, but to deploy the bowline requires both the vessel to be fully into the berth and a person at the bow (which may be risky). Likewise a stern line can only be deployed once the craft is fully into the berth, whereas rigging a line from the midships cleat to drape over the first cleat on the end of the finger berth allows the craft to continue to drive into the berth before the line arrests forward movement and brings the vessel alongside the berth. The craft can be held in gear to keep the vessel alongside while other lines are deployed. Great care must be taken to ensure that this line is secured to the craft’s cleat before load comes onto it as no one on board should hold a line to arrest the boat’s movement – it is too dangerous.

‘Boat 7’ again drives into the berth approaching into the wind. By timing the turn right, the momentum again carries the vessel onto the berth, compensating for the effect of the wind pushing the craft off.

When approaching a berth, also consider whether it is ‘closed’ or ‘open’ to you. Approaching from the ‘open’ side means that the craft’s momentum is onto the berth. As helmsman, decide whether going past the berth and turning to approach from the open side makes things easier – it’s not always necessary or possible but is always worth considering.

Before entering a berth, always rig fenders to the correct height both for the side the berth is on, and also along the side that may engage with another craft. These should be higher and there should be three or four. Sometimes there is no choice when coming into a berth but to settle alongside another craft. This is fine so long as the fenders are deployed, your vessel engages parallel to the other craft and it is slow. A roving fender in the hands of a crewmember where deck access is safe always makes sense.

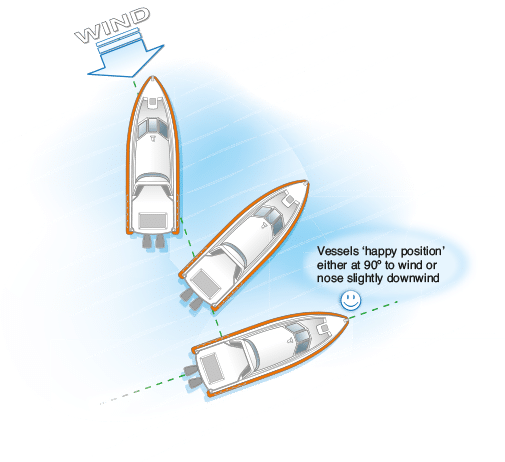

The heavy stern of a vessel and relatively light bow means that wind on the bow will quickly ‘grab’ the bow and push it downwind to lie roughly beam on to the wind.

This occurs to all powerboats, but how quickly the boat reaches this position will vary according to the craft and the wind strength.

Of course, at the same time as the craft is blown to lie side on, it will also start to travel downwind as it gets pushed across the surface of the water.

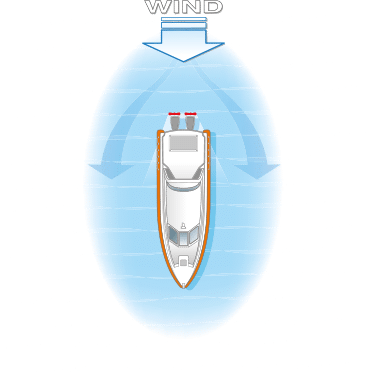

All powerboats can be held very comfortably stern to wind. Left sitting stern to wind the craft will eventually move to lie beam on, but this will take much longer when the starting position is stern into wind than bow into wind.

All powerboats can be held very comfortably stern to wind. Left sitting stern to wind the craft will eventually move to lie beam on, but this will take much longer when the starting position is stern into wind than bow into wind.

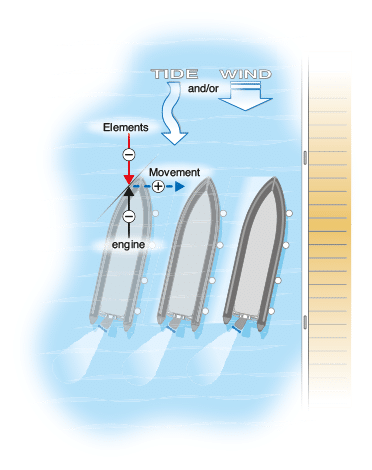

Tide or stream, of course, may also have a big effect on your manoeuvre. The general impact of any form of stream is simply to move you around in a marina. If you are lucky, the stream will run through the berth, acting directly against you as you enter the berth to give you good control as water is flowing past the hull.

As you may recollect, this stream can be harnessed to great effect to create an effect called ‘ferry gliding

This article is partially reproduced from the ‘Boat Handling’ chapter in the new RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook.

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK and Marine Education in Poole and Lymington (www.powerboattraininguk.co.uk / www.marine-education.co.uk).

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK and Marine Education in Poole and Lymington (www.powerboattraininguk.co.uk / www.marine-education.co.uk).