Paul Glatzel discusses some of the strategies that can/should be employed in difficult weather conditions …

Knowing how to deal with rougher conditions is a key part of becoming a more experienced ‘advanced-level skipper’. In this article we’ll look at some of the key things to think about to stay safe when it kicks up a bit so we can be ready for the next article on the boat-driving aspects of being out in rough water.

Unless you only ever go out when there is no wind, at some stage you’ll face conditions beyond what you reckoned you were going to experience. Being an effective, safe and successful skipper starts with being able to say no. Whether you are a relatively new skipper, a commercial skipper running RIB trips, the captain of a large ferry or a lifeboat helm, you will face a time where the best decision is to stay alongside and not go out. But this is often easier said than done, so what can you do to make this easier and also ensure you make that right initial decision?

I tend to look at things in the sense of pluses and minuses – I think through all the issues and see how the equation balances. A couple of minuses may be fine (depending on what they are), but when the negatives outweigh the positives, it’s certainly time to walk away. As a place to start, I have always worked on the basis that if something doesn’t feel quite right, then it probably isn’t – a gut negative feeling will be a big cross in the minus column.

As a skipper, though, you have to consider many angles. Let’s start with weather: what’s the weather like now, and what will it be like during your planned passage and also in the few hours after you should be back ashore? These last few hours are easy to overlook, but if you run into issues that delay you, you risk being whacked by a storm that was predicted and you could have avoided. ‘Shoe-horning’ your trip into a tight window can give you no escape room, so obviously the weather window and the weather itself can be a tick or a cross.

The people on board are a big factor – both the crew/passengers and you. As skipper, do you have the skills and knowledge you need, and are you backed up by people with the right experience? A trip across glassy seas one day could be fine with a group of inexperienced younger and/or older people on board, but as it gets rougher you will want a higher degree of capability there in the boat with you. Who is going to look after the boat if you are incapacitated? Who will operate the radio if there is a medical issue and you need to seek backup? Remember too that with very few exceptions, when people are on a boat they are there to have fun, and being pushed beyond their comfort zone is not everyone’s idea of a fun day afloat.

The boat is obviously a big factor too. A nice 7m open-bow sports boat shines when it’s operating on a sunny calm day as these are great dayboats. When it kicks up, you may find the hull is less capable than you imagined, and what was a great seating area up front has turned into the biggest water scoop known to man/woman. Learn about your boat and its capabilities slowly, and don’t necessarily believe the brochure when it says it’s the best rough-water boat ever – ease it into these conditions over time and form a view yourself. Tied into the boat is the kit you carry and wear. Life jackets and suitable wet-weather gear will be key, as is a boat that is well set up for rougher conditions. Items in lockers (especially at the bow) can take a hammering, so are they secured? Are they up to the job? And do you have enough/the right means of issuing a distress signal or solving problems on board?

Finally, where you plan to go out is key, as is whether you go alone or not. A 5-mile passage as a single vessel along the west coast of Ireland fully exposed to what the Atlantic can throw at you with no escape routes is very full-on. In contrast, a 5-mile trip through Poole Harbour in a force 6–7 with another boat alongside you whose skipper has some good experience will be wet and lumpy but very different.

Remember, you as the skipper need to make the decisions; no one else can do so and it’s you that will be judged in the event that it goes wrong. If you feel uneasy, don’t go, or try to convert one of the negatives across into the positive column – perhaps by amending the plan or who is coming with you.

So let’s look in a little more detail at how we can predict what conditions we are going to face. Anywhere we go boating we should be able to understand the wind and tidal conditions we’ll face and how these elements will interact with each other and the land masses where you are boating.

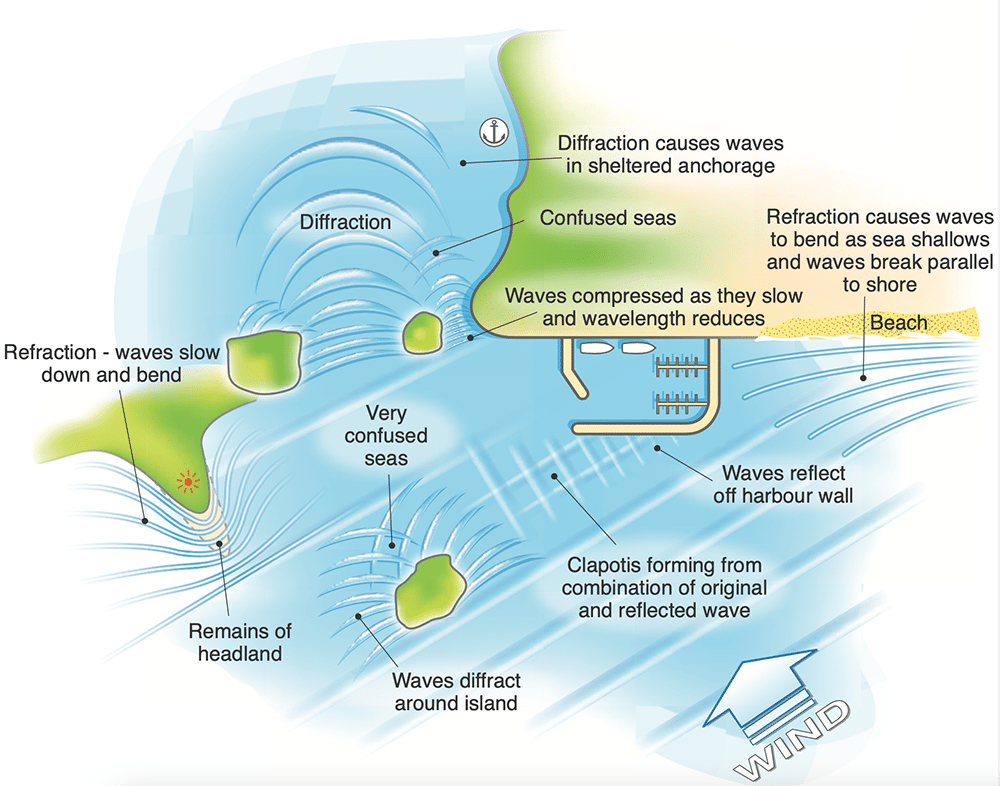

Image from RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook

This image from the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook shows how waves can interact with the various features we experience afloat and how these may impact the conditions you face.

Diffraction, refraction and reflection are predictable reactions, so we can look at a chart for the area where we intend boating and try to predict the conditions we will face.

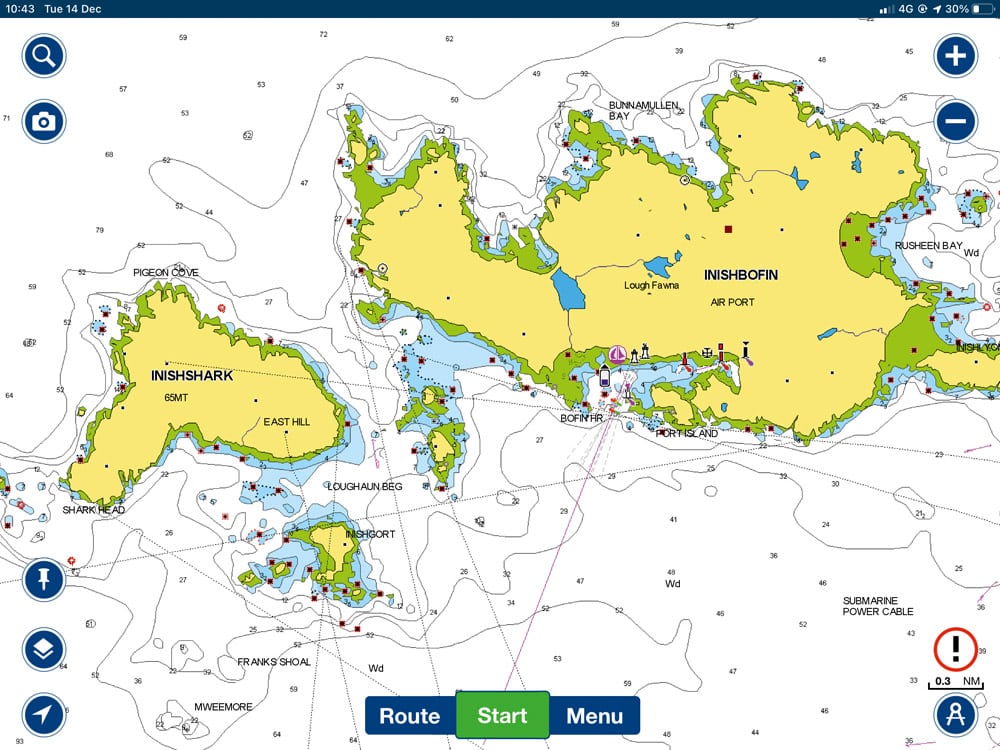

Here we see a screenshot of the Navionics app showing the area around the Inishbofin and Inishshark islands off the west coast of Ireland. As you can see, there are many islands and areas of shallower water. Let’s imagine that we have no tide but we have winds of force 5–6 from the south-west, thus hitting the islands from the bottom left-hand corner of the image.

Below Inishshark we have the small island of Inishgort. What will we experience in the area of water between these two islands? Given what we have seen in the previous RYA image, we can apply these same principles to this location.

My first thought is that the wind is going to funnel up into this gap and, depending on the height of the land, potentially race through the area between the islands, so we may see a wind speed there greater than predicted. We could also get waves reflected off the coast on the southern side of the large island – especially if its vertical cliffs reflect well, unlike a shelving beach that may dissipate some of the wave energy. There are a few shallower areas too, and this will give rise to rougher conditions in those particular locations as water moves from the deeper water (the white areas) to the far shallower areas (blue areas). That could be helpful, though, in removing some of the energy from the waves, leaving calmer waters behind these shallow areas. Around the northern side of Inishgort we may get refraction and/or diffraction, and, depending on tidal height, this may be worse if waves are funnelling through gaps in the islands.

So would we want to go through this gap? Well, it depends on all of the factors we have listed, and we haven’t even started to look at the waves and how our boat handles in a following sea yet. Equally we have assumed there is no tide, and whether this is running against or with the wind will have a massive bearing. In this case we may well not have to take on the gap, as there is an easier route by heading south of Inishgort and then turning north, but hopefully what we have provoked here is a bit of thought in that by using a chart, knowing the wind and tide and having some knowledge of wave theory we can second-guess to a large extent what conditions we may face. Of course, there are some big dollops of educated guesswork in there, but that’s far better than no thought at all!

In the next article we’ll look at handling waves and creating a strategy for driving in rougher conditions. In the meantime, why not have a look at an area on a chart and see how you interpret how wind and tide will react around land areas.

Have fun afloat!

Tune into PBRTV YouTube channel and watch our tutorials with Powerboat Training UK

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK in Poole and Lymington (

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK in Poole and Lymington (