That is the question. Paul Glatzel considers a classic problem all boaters face, the boating weather …

One of the most difficult decisions faced by a skipper is whether or not to cancel a trip due to the weather. In contrast to those boating in the Med over the summer, where the conditions are generally pretty consistent, a UK-based skipper has to contend with the inevitable variations in weather that the UK throws at us.

Predictably, this places the skipper in the position, ahead of a trip out, of needing to consider weather forecasts and then come to a decision – to go or not to go. Of course, often it’s a really easy choice to make. Big winds means don’t go and no winds means crack on, but more often than not, we’re faced with that bit in the middle where it’s all a bit more messy and unclear.

As an instructor, I know that I’m always learning, and it’s fair to say that one of the areas I’ve learned a lot about in the last few months concerns weather information/forecasts, where we get them and when we need to be careful about what we’re looking at.

Historically, where we got our weather information from was pretty simple, as all we had to look at was the Met Office Inshore Waters Forecast for the area in which we were boating. Around the UK, there are 19 Inshore Waters areas covering up to 12 miles offshore. These are really large areas, and within each one, the weather experienced can vary massively along the coast. Inevitably, as apps and websites appearing to offer really localised weather forecasts have proliferated, so the majority of boaters have moved to identify a favourite app or website and get into the habit of just typing in a location, e.g. ‘Poole Harbour’.

In the last few months, the question I have sought answers to is: how accurate are these app/website-based forecasts, and why do they often seem to vary noticeably between apps for the same location? The answers I’ve found are enlightening and pretty scary in equal measure and certainly explain why we experience such inconsistency between different products.

Weather models underpin the forecasts we look at. These models are based on computer programs that analyse the source data gathered and output their results. There are numerous weather models around, with some being run by governmental organisations while others are operated by commercial companies. These models appear to be based on a grid system of ‘nodes’ placed over the entire world. The models then seek to predict the weather either at these nodes or perhaps at the midpoint between them.

Image 2 – ‘The node spacing between different models can vary massively, impacting the accuracy of the forecasts.’

The distance between these nodes can vary massively – 27km in some models and perhaps only 1.5km in others. This matters hugely, as if you imagine an area like Poole Harbour, it’s quite feasible that the nodes will not land on any part of the harbour, and therefore the modelling completely ignores its existence. What you would then get as a forecast for Poole would be an average of the forecast for the four nearest nodes.

Further complicating matters, some models don’t factor in topographical features/changes, and some struggle to model the weather where land interacts with water (like the coast!), both of which could have a particularly profound impact on the areas we are interested in as boaters. Finally, another factor that impacts which models may work best for us is that some models may be aimed at the US market, and while these may also predict UK weather, they are less likely to be accurate, while others may be aimed at the UK or European market and thus be more accurate. The tough question for all of us is: which are the better ones, and how can we determine them?

A weather app I have used for a long time is XCWeather. For a couple of years, however, I found the forecasts for Poole Harbour to be wrong too often. It was this that prompted my desire to understand a bit better how these apps and websites work. If you search around the app, nothing I can see tells you which forecast model is being used. The website version, however, indicates that the model used is the GFS model. GFS is a US-based weather model with nodes spaced 27km apart. Everything that I’ve read indicates that while it is the best for the US, it’s not as good for UK weather. (See image 2)

Two (paid for) weather apps I have started to use far more are ‘PredictWind’ and ‘WindHub’. Both of these use a number of models and average all of the forecasts they use, or allow you to look at the forecasts from individual models. Both suggest that one of the best for Europe and the UK is ECMWF (which has 14km node spacing). The UK Met Office’s UKV2 model, with nodes at a spacing of 2km, is used in these too. Models also seem to vary in terms of how often they recalculate the weather, and they don’t often make clear whether the forecast being referred to was calculated, say, 3 or 12 hours ago.

So what does this all mean in practice?

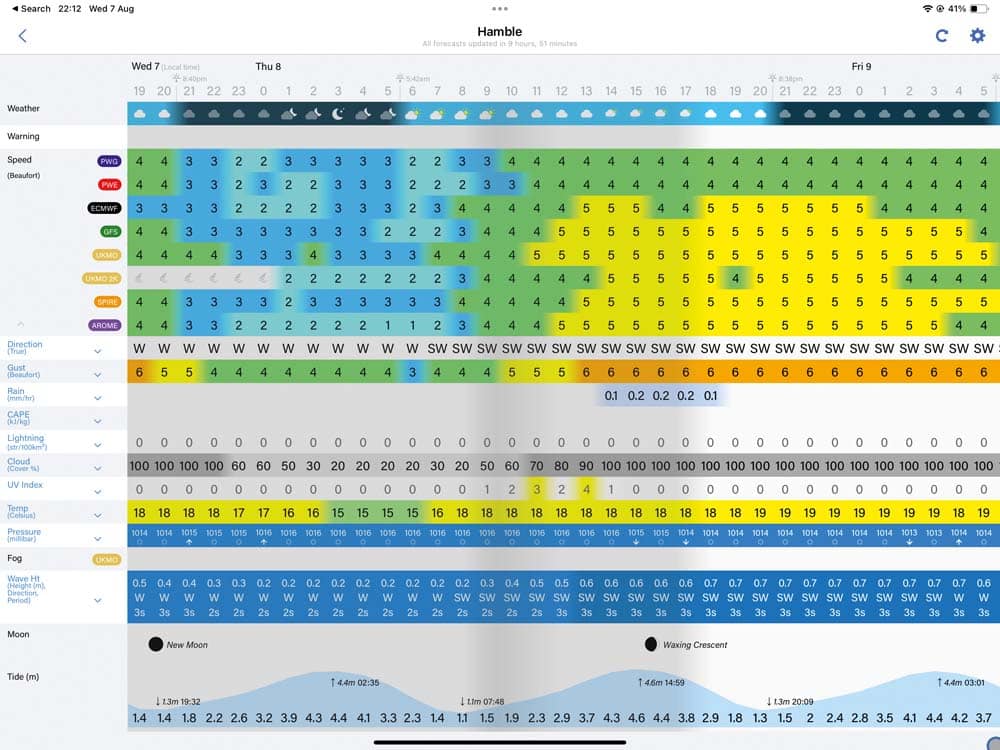

Basically, it means that we as skippers need to invest some time in working out what model best suits the areas in which we boat. We need to look at live weather data from weather stations and compare this to what the forecasts are giving us and so form a view of which model to use in which location. My approach tends to be that I’ll still use XCWeather for a quick glance at the current and upcoming conditions, but if I want to feel more confident about what is coming, I’ll look at PredictWind and WindHub and what the individual models are telling me. This gives me the opportunity to build up an understanding of what works best for me. Although I have mentioned these two apps, there are plenty out there, so do spend a bit of time digging around and getting a feel for what will work best for you. (See image 3 and 3b)

Image 3 – Screenshots of PredictWind and WindHub – weather apps

Be realistic with forecasts, though. The longer into the distance you look, the less likely the forecast is to be accurate. I tend to work on the basis that two to three days ahead, the forecast is reasonably likely to be accurate and, as time passes, will get more so. In my opinion, looking at a forecast a week in advance can give you a rough idea, but there is little point in basing any plans on this.

Image 3b – Screenshots of PredictWind and WindHub

In summary, as with so many things in life, you appear to get what you pay for. It certainly seems that if you want access to the best weather data through apps, you will need to pay a bit. Free weather apps can be absolutely spot on, but by ensuring that you have access to the most relevant weather models, you are increasing the probability that the forecast that you are presented with is consistent with the weather that turns up on the day.

Finally, don’t forget two key points: 1) what we are getting is a forecast, not a guarantee – don’t be surprised if a forecast is wrong; and 2) a good skipper knows that if they feel it’s not right to go, they don’t go. Keep safe and have a great time afloat!

Any Illustrations in this article are by Pete Galvin and are taken from the RYA Powerboat Handbook/RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook, available in print or e-book from the RYA shop: rya.org.uk/shop.

Take a look at more boating tips in our extensive tuition section.