Boating Tuition – In the seventh of this series of Back to Basics articles, Paul Glatzel underlines the importance of expecting the unexpected …

Staying safe at sea

Previously in this series of articles we’ve looked at the skills needed to get afloat and have fun, to explore new locations and to be able to handle your boat in a marina setting. We all hope that everything always goes well, but sometimes things do go wrong and in this article we’ll look at how to react to these situations and keep you, your family and friends safe.

Use a kill cord and use it correctly

Let’s start with some of the subjects that are covered on every powerboat course you could do – wearing the kill cord and keeping one hand on the throttle and one on the wheel at all times. So why do instructors bang on about these things?

The kill cord we all tend to see is the curly red cord that attaches to a switch near the throttle position. The idea is that the kill cord should be attached to the person driving, meaning that, in the event they leave the helm position, the engine is cut – whether this is through some violent manoeuvre or simply walking away from this position. It seems simple, doesn’t it? But many people don’t wear the kill cord and argue that they haven’t ever fallen from a boat and therefore this isn’t a real or likely risk. And yet, we buy insurance policies to insure against things that almost certainly will never happen. Wearing a kill cord is simply another insurance policy – you wear it, just in case, to protect those on board and other boaters from an out-of-control boat, even though, in all probability, nothing will ever happen. Wearing the kill cord may save a life or prevent injury and costs nothing.

The Cowes harbour master has issued a notice to all boaters to wear a kill cord following serious injury to another boater at another port.

Where should you keep your hands?

In a similar way, operating with one hand on the wheel and one on the throttle at all times is a form of insurance policy. This policy insures against the risk of gear failure or the need to take sudden avoiding action at slower or higher speeds. Again, this may seem an unlikely possibility, but as someone who has experienced gear failure at over 60 knots that led to a dramatic change in heading, I can promise that having my hand on the throttle, allowing instant speed reduction, made all the difference.

Skipper’s duty of care

As a skipper, you have a real duty to keep all on board your boat, and those on the water around you, safe. You need to make sure that those on board understand what they need to do when afloat, and this starts with a really decent safety brief. Doing such a briefing sometimes feels a bit awkward in a social situation, but all you are doing is showing how to use the kit you have on board and where you stow things – for example, how to wear and deploy the life jackets, where the flares are kept and how to set them off, how to send a DSC distress alert and when to make a Mayday call, where the fire extinguishers and first-aid kit are kept and so on. It’s well worth writing down the safety brief and keeping it saved on a tablet, smartphone or just printed on board. Doing so means you won’t miss any key points.

Man Overboard

The Mayday message sent after pressing and holding the Red DSC distress alert button: Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. This is RIB Evolution, call sign MTG6Y, MMSI 235899991 Mayday Evolution, call sign MTG6Y, MMSI 235899991. Position one mile south of Bournemouth Pier, man overboard. 2 persons on board, immediate assistance required. Over.

If it does go wrong, you and your crew should have allocated tasks. For example, if you have a person in the water unexpectedly (‘man overboard’ is the accepted terminology irrespective of their sex), you should divide up the tasks. Get one person pointing without stopping until there are hands on the casualty – even in calm conditions it’s easy to lose sight of the individual, especially if they are low in, or slightly under, the water. Get someone else to make a distress call (see below), while whoever is helming gets the boat into position ready to bring the casualty back on board.

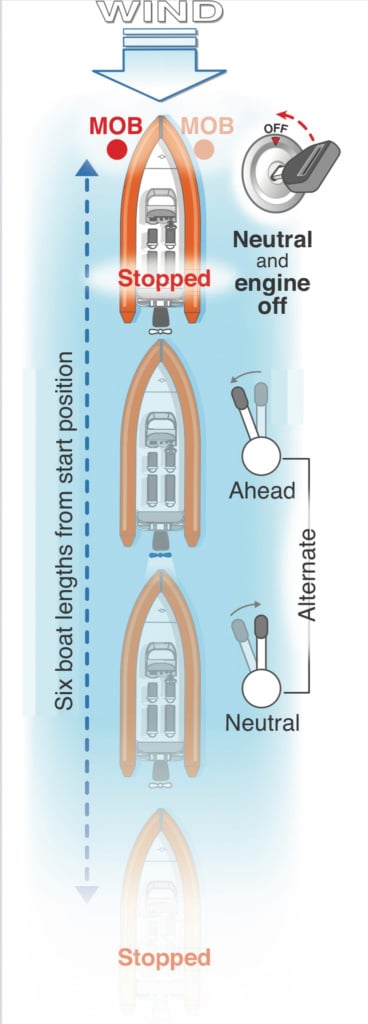

MOBv1: Position boat six boat lengths directly downwind from the casualty. Go into/out of gear at minimum speed towards the person. Kill engine immediately when alongside.

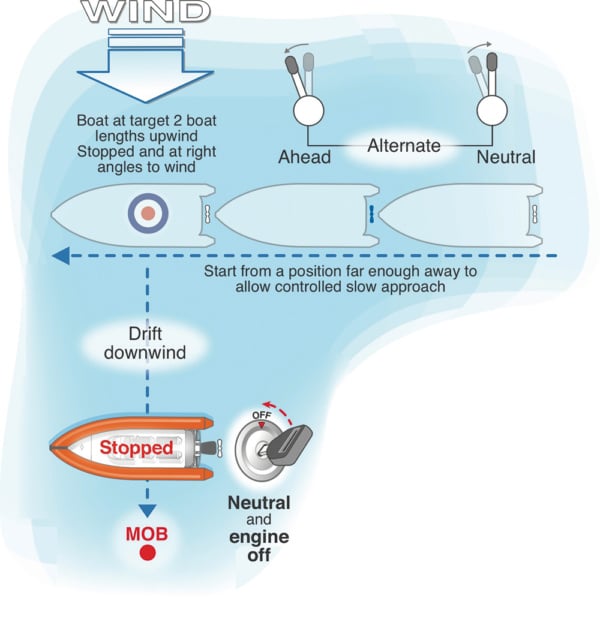

MOBv2: Position boat two boat lengths directly upwind from the casualty. Drift down towards person, adjust position to stay side on to the wind. Kill engine immediately when alongside.

Getting back to the person in the water is best achieved by approaching in one of two ways:

Being effective at recovering a person from the water takes practice. Make sure that every few times you head out, you do a fun session with the rest of the family or your friends practising approaching and recovering a casualty. Use a weighted fender (a line coiled and tied to the fender works really well) and never a real person. Make sure too that you do a first-aid course. I have never heard anyone at the end of a one-day course say anything other than it was a really beneficial day, so get yourself, and even perhaps the kids, booked on one. Likewise, if you haven’t done the VHF Radio course, do that too.

Keeping safe afloat is very much about your approach to boating. Take things slowly, communicate well, brief others and practise the skills you need to – ‘just in case’. All these things are just another of those insurance policies – one hopefully you will never need.

Keep safe and have a great time afloat!

Illustrations in this article are by Pete Galvin and are taken from the RYA Powerboat Handbook/RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook, available in print or e-book from the RYA shop: rya.org.uk/shop.

Read the full Back to Basics Series:

Back to Basics – Part 1: The ‘COLREGs’

Back to Basics Part 2: Interpreting your Charts and Chartplotter

Back to Basics Part 4: Buoys and Pilotage

Back to Basics Part 5: Boat Handling

Back to Basics Part 6: Marina Handling

Back to Basics Part 7: Dealing With Emergencies

Learn more in our Tuition Section