Mark Featherstone turns an unfortunate incident into a learning opportunity as he discovers that there’s a whole lot more to rope than you might think.

[Lead image: Copyright Alexeys/iStockphoto]

The phrase ‘money for old rope’ comes from the days when old rope was picked apart, applied with pitch and used for caulking on ships to make them watertight. Today, though, old, worn or damaged rope can cause water ingress of a different kind if the rope that is tethering a vessel parts and the boat breaks free, as I found out to my cost last year.

A sobering tale

Last autumn I left my boat safely tucked up for the winter at a local marina. Storm Claudio brought strong south-westerly gales in from northern France that swept through the marina, tearing a brand-new 44ft boat from its berth, where it had been since delivery. Ricocheting down the fairway and hitting five boats along the way, it finally came to a halt having hit my boat last with huge force and doing significant damage. Not surprisingly, this upsetting episode got me thinking about just how important the right rope is, especially when you think of how much we invest in our boats, not to mention keeping our loved ones and friends safe.

Replace any lines in poor condition immediately

Standing in front of the rope display in your local chandlery, you’re met with an array of colours, choices and sizes at different prices. So what should we be looking for? I headed off to the Malvern Hills to visit the English Braids rope factory and discovered that there’s a lot more to rope than meets the eye.

Rope composition

Let’s start with the composition of rope. Usually, the rope core is made up of any one of three materials – nylon, polypropylene or polyester. Polypropylene is a cheap substitute, often referred to as ‘fisherman’s rope’, that floats and has little weight, which I really don’t recommend using for mooring lines. Nylon has more stretch but absorbs more water, so it can be heavy when wet, which can also weaken it, and the lines may squeak as the fibres rub against each other if you’re tied up on a dock, which could disturb you, your crew and your neighbours! It is also susceptible to UV damage – if you have a nylon rope that has gone yellow it means that the rope has been damaged and consequently the strength of the rope has been affected. Most rope manufacturers now recommend polyester for mooring lines, which is UV resistant, has slightly less stretch but is more abrasion resistant, and strength is retained when wet.

The strands of yarn twist around in a colourful maypole dance!

Rope is made as the flat yarn is twisted into strands. A high-quality rope manufacturer such as English Braids will make an S & Z twist, which means that there are an equal number of counter twists to make a balanced rope. On cheaper ropes you might cut the end off and it will unravel because it’s made of one twist, which will of course cause issues. The twisted strands then go off to make either a three-, eight- or 12-strand core where the strands are twisted together or plaited.

Yarn at the English Braids factory

These cores can also have covers, and this braid-on-braid or double-braid configuration is what I would recommend for mooring lines, as they make for a strong, flexible rope that offers extra protection from chafe and UV and is more comfortable to handle. We were lucky enough to see these braided ropes being made, and it brought to mind a maypole dance as the fibres don’t just wrap around the core but twist in and out around themselves before covering the core – quite a colourful spectacle! But what rope do I need?

The author at the English Braids plant.

Mooring Lines

Let’s start with what I believe is the most important rope on a motorboat, yet one that is often taken for granted. For my own 44ft vessel, I use 12mm double-braided polyester mooring lines. These flake and coil nicely and have an extremely high working load with some stretch. I think it’s important that the rope is easy to work with and soft on the hands, as most of the time the rope handling is done by our friends and family and we need cruising to be not just safe but a pleasurable experience for everyone.

Here seen on top, a nice new healthy mooring line

Mooring lines probably do more work than any other equipment on board. Let’s face it, the majority of our boats spend their lives on a pontoon or mooring and will be susceptible to a multitude of factors causing weathering as well as wear and tear. They’re working hard to keep your boat on the dock day and night in all weather conditions and are often exposed to extremes – wet and dry, hot and cold, calm conditions and wind that is constant or gusting. Not only that, but tidal range and excessive wake from passing boats all take their toll on those lines.

Notice the outer fray to the mooring line.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that your life and the life of all those on board can literally depend on that rope not failing, so regular inspection is really important. Therefore, have a good look at what you are mooring to – a rusty bollard or cleat will act like a cheese grater on rope, chafing the covers and separating the braids. Inspect the rope each time you visit your boat to make sure there is no chafe, stress or distortion on the cover and no filaments of the inner core coming out through the cover, which is a warning sign that the strength of the rope is compromised. When securing your boat to the dock, the mooring line needs a good bit of length as a short line will result in snatching. This will degrade the rope rapidly and may cause damage to your deck fittings, leading to stress cracking on the gelcoat of the deck around the cleat. Also, ensure that you have enough spring lines out to reduce the load on your mooring lines. If you’re leaving the boat for any longer than 12 hours, make sure you have two mooring lines aft and forward and at least three spring lines – or four if your boat is over 10m. When you leave your craft on that lovely sunny day, you can’t predict what conditions the lines are going to be subjected to, but out of sight should not mean out of mind. Tide, wake and wind will change, and if a howling gale of wind comes up, you are relying on those ropes to keep your boat safe, and, as in the case of my experience, you will keep other boats safe too.

Always buy high quality rope, cheap rope is likely to be of poor quality and lesser breaking strain.

In researching this subject, I spoke to Paul Honess, Leisure Marine Sales Director at Marlow Ropes, and asked him for his advice on buying mooring rope. His top tip is to use rope that has been supplied by a high-quality manufacturer and to check the price – if it looks very inexpensive, it’s likely to be of poor quality. ‘Your boat is likely the second-biggest purchase of your life after your house,’ he stated. ‘Rope is one thing you shouldn’t therefore be trying to save money on.’

Paul also warned of cheap imports such as pre-packaged mooring sets with a bow, stern and two spring lines. ‘If you open these mooring lines up, they tend to have a lower twist and be loose in construction, which will allow ingress of debris and therefore abrasion. Although they may offer a breaking strain that looks to be enough, they often don’t have the weight and the break load may not be correctly stated.’ Good advice!

At your local chandlers you are met with an array of colours, choices and sizes.

English Braids actually stretch and heat the cores to 185 degrees, which gives the rope better integrity than cheaper ropes. Buying cheaper ropes is actually a false economy because they may only last a season and a decent set of ropes will last you a lot longer and be more reliable. I recommend changing the rope every four seasons if the boat is out of the water for the winter, and every two seasons if she’s left in. However, if your boat is moored on Lake Windermere, for instance, there will be less wear and tear than if your boat is moored against a tidal sea wall, so use common sense!

Premium pre-spliced dockline

English Braids also cautioned against mixing and matching your lines, so make sure they are all the same, and they suggested using chafe covers such as the Chafe Pro, which use hook and loop fastenings to protect the rope from abrasion. I always have a 300mm eye spliced into the end of my mooring lines, and a chafe cover for the loop stops rubbing against cleats and mooring bollards. There are also covers available that you slip over the line to prevent chafe from the dock, and chafe mats that will protect the deck.

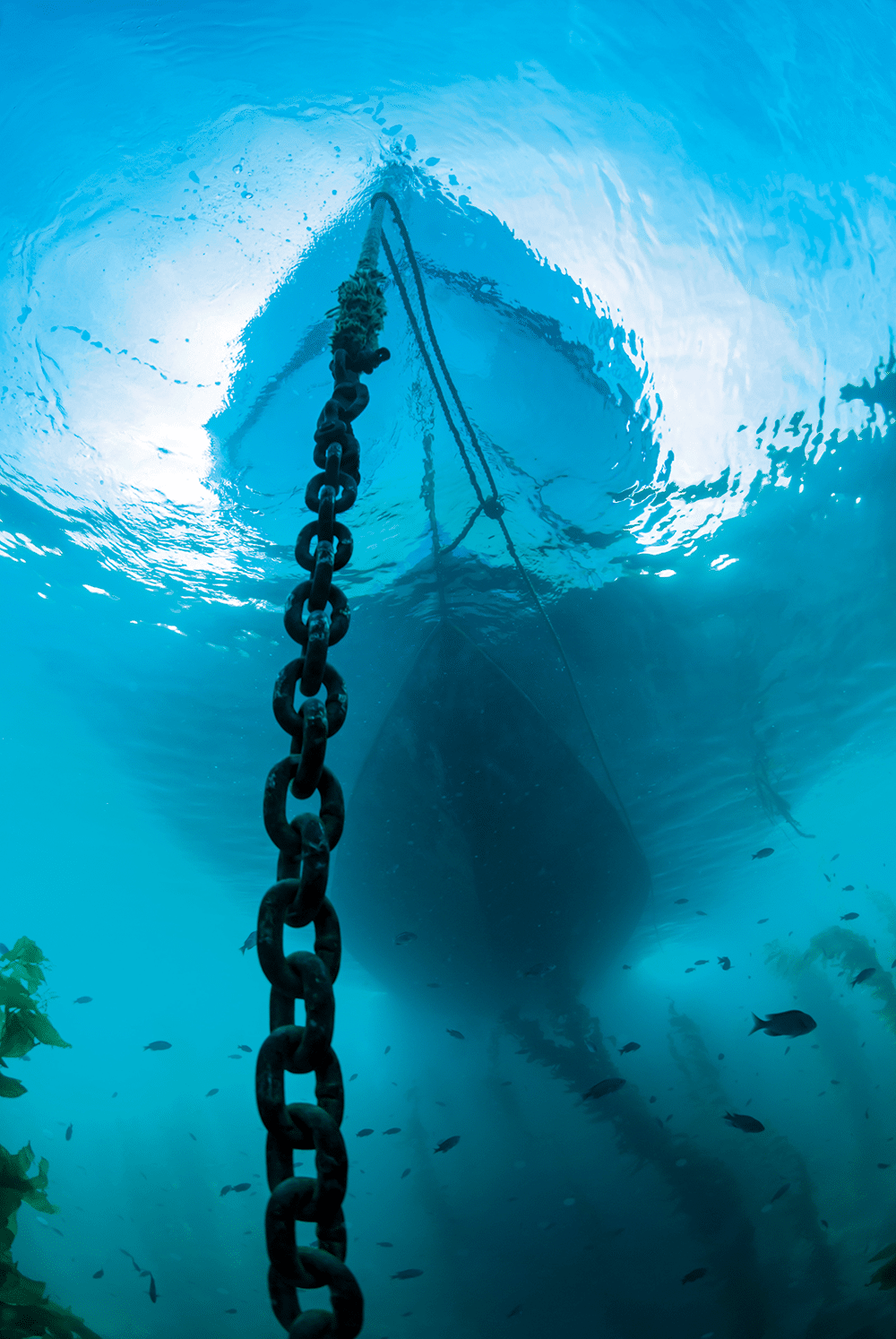

Anchoring

If your anchor configuration uses line, then getting the right anchor line is important for two reasons. Firstly, as you anchor up in that beautiful bay watching the kids jump into the sea, you don’t want to suddenly look up and see the cliffs coming towards you at speed because your anchor rope has parted! Secondly, you must think of your anchor as part of your vital emergency equipment because you may need to deploy it if you suffer engine failure and are drifting towards the shore. Eight-strand nylon line is widely recognised as the standard for anchor line as the nylon will give you stretch that will absorb shock loads.

Anchor warp made fast to a sufficiently long length of chain

When choosing the right diameter for your vessel, check the manufacturer’s data sheets and always work on their minimum working load. You should always have a length of chain between the anchor and your line as this will help the anchor to dig in, thereby reducing the effect of pitching, and it will protect the line from the seabed and abrasion from sand and rocks. Have enough line and chain on board to provide scope for at least six times the maximum depth of water expected, and more may be needed in heavy weather. When you bring your anchor back up, check your line as rocks may have chafed it and, as it lay on the seabed, sand may have got into the fibres, which will abrade the line as it stretches and relaxes. Because the anchor line doesn’t have a cover on it, remember that it’s more susceptible to UV damage, and a white line turning yellow is an indication that the rope has degraded. As soon as you can, flush your anchor locker through with fresh water.

Egyptian rope used the same S and Z twist as modern rope.

Tow lines

If you’re ever in the unfortunate circumstance where you’ve lost all power, you may need to be towed. It can so easily happen – perhaps the culprit is fishing rope wrapped around your prop, or you might have suffered an outright engine failure. The rule of thumb is that it’s best you accept a tow from the vessel coming to your assistance. Think about it: if you start throwing your tow line at another vessel, the chances are very high that it will snare in the tow boat’s propellor. The RNLI will always pass you their line, and I recommend making this a regular part of your crew briefing so that you all know exactly what to expect.

When serving on the Salcombe Tyne Class lifeboat crew, I remember one particular lifeboat shout to an old, traditional sailing boat trying to cross the bar into Salcombe under sail. She lost wind as she came under the cliff and the crew couldn’t then start the engine. When we arrived on the scene, she was yards from the rocks, and so we duly prepared to throw our line. Unbelievably, the skipper refused to take our line and insisted we take his instead, which would have put both boats at risk. For some heart-stopping minutes he refused to budge, then suddenly one of his crew members leapt up onto the bow and shouted for the lifeboat’s tow line. His quick action saved both the boat and the skipper and crew, but being prepared in advance as to any such plan prevents confusion and precious lost minutes.

In conclusion

Rope is the most used, often the most abused and frequently the most ignored item of equipment on your boat. However, when you consider the cost of the boat and the other equipment you buy, you can’t afford to stint on the quality of this item. Always buy the best rope you can afford. Look at it as an insurance policy in its own right – one that will not only protect your investment, but most importantly you, your family and anyone else aboard. Therefore, value your ropes and warps and take care of them. They’re a commodity that, until now, you may not have credited with all the value and importance they fully deserve.

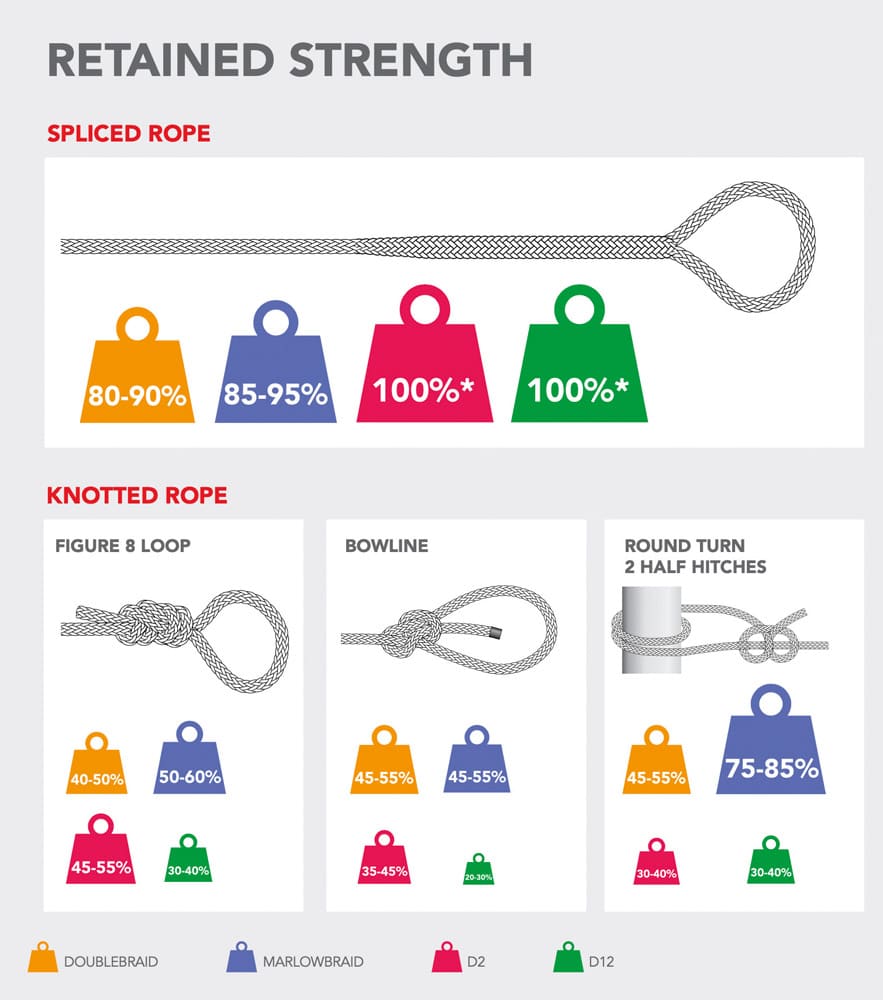

Rope strength

A new rope’s tensile strength is a measure of its breaking point tested under laboratory conditions in the manufacturer’s factory. Here, the load that the rope is expected to carry is increased until the rope breaks. Some manufacturers such as Marlow Ropes specify the minimum break load on their products. However, it is your responsibility to determine the appropriate factor of safety and the safe working load. In this regard, the main factors to consider are:

- Static load – the boat’s size and tonnage

- Dynamic load – tidal movement, prevailing winds and, for mooring, the number of lines employed

- Abrasion – the type of mooring used

- Temperatures – UV will damage the rope

- Strength reduction due to splices or knots – a spliced loop is far stronger than the tied alternative (see pic.)

- Consequences of rope failure – damage to the boat or putting the crew in danger

The effect of splices and knots on rope strength

Trying to work out a safe working load can appear to be something of a dark art, so my advice is to work on 20% of the breaking strain to determine your safe working load. For example, a rope with a 1000kg breaking strain will have a safe working load of 200kg. Use that calculation and you can’t go far wrong. Remember, splices and knots will affect the strength of the rope. I strongly recommend, therefore, using a chandlery or supplier who can both advise you on loads and splice in your loops for you. Always err on the side of caution. Your safe working load is a far smaller number than the breaking strain.

Rope care & storage

Your ropes are an investment and should be looked after accordingly. These guidelines will help you maintain your ropes in terms of their durability, performance and reliability. General good practice includes inspecting all ropes regularly to check their condition and ensuring a rope’s suitability for its intended use.

So check for:

- Chafing or seriously worn surface areas

- Kinks/twists in the rope

- Movement in splices & joins

- Broken, cut or frayed strands

- Chemical exposure and degradation

- UV degradation

Season’s end

- Never allow rope to become kinked or twisted as this will impair its life and usability; ideally store in a figure of eight.

- Ropes should be stored under a suitable cover and not left to withstand the elements at the end of the season.

- Leave them clean and dry, out of direct sunlight and away from extreme temperatures.

- Never store ropes on concrete or dirty floors as dirt and grit can work into the strands, cutting the inside fibres.

- Keep away from all chemicals.

- Sand and salt crystals are naturally abrasive and will affect the life and efficiency of ropes, so soak in fresh warm water.

- Ropes can even be washed on a gentle cycle with mild detergent.

Rope’s history, the present and its future

Evidence has been found that man has been using rope since before the invention of the wheel and that it dates back to the most ancient of times. The Egyptians were the first to create rope-making tools as rope became essential in moving materials for building pyramids and monuments. Marlow’s head office in Hailsham has a sample of Egyptian rope found on the banks of the River Nile. Remarkably, papyrus or Nile reeds were formed into a strand, and then three strands were made up and laid with opposing twists (S & Z) – exactly the same principles that are employed today.

In previous centuries, hemp rope was traditionally made in a ‘ropewalk’, which was a long, low building that could extend for a quarter of a mile! Long fibres would be laid down and twisted together to form one strong rope. The strength of the rope came from these fibres being wound together multiple times over. The Historic Dockyard in Chatham still has a working ropery and is well worth a visit.

Rope technology has come a long way since then, thanks to the use of Dyneema rope. This is a non-woven composite material used in high-strength applications and is constructed from a thin sheet of ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), laminated between two sheets of polyester. Marlow Ropes are constantly innovating and supply Dyneema to NASA for the Mars landers. There are projects such as robotics where rope is used, as it’s much lighter than wire and easier to use and terminate.

Sustainability is very much in evidence in today’s rope industry and many high-quality manufacturers offer rope made from recycled waste plastic bottles. We were amazed to learn that 100% of Marlow’s dock lines are made from recycled and sustainably sourced materials. Plastic bottles are manufactured into recycled polyester (PET) to produce a yarn that has the same specifications and technical characteristics as polyester yarn. Provided the yarn hasn’t been mixed with any other chemicals or fibres, at the end of its life, it can be recycled itself. Turning the old adage on its head – money can now be made from old rope!