As Giovanna Fasanelli, PBR’s environmental expert, reports, the truth about sargassum seaweed may be both complex and elusive, but either way, it’s certainly of interest to us all.

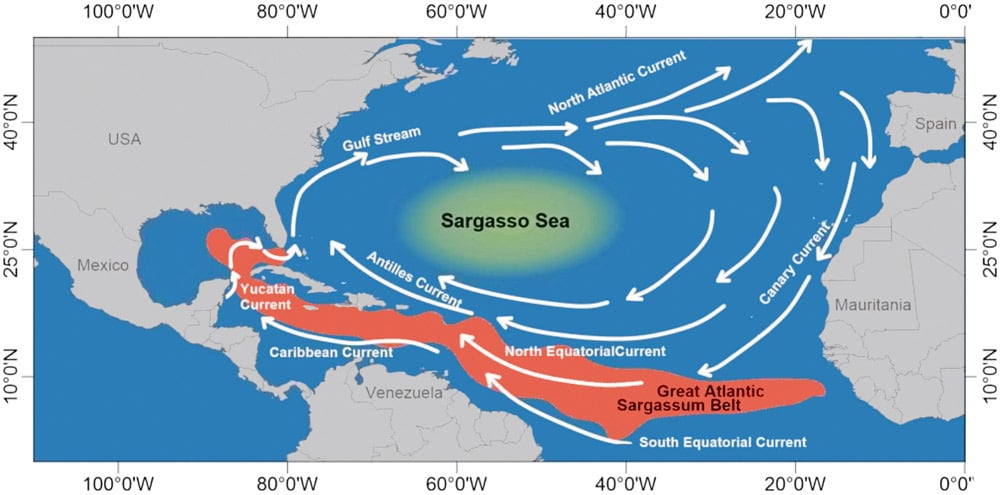

Let’s be clear: the colossal floating gardens of sargassum seaweed that Columbus reported in the late 15th century were, and still are, a naturally occurring phenomenon that defines the Sargasso Sea – a roughly 5 million-square-kilometre expanse of open water east of Bermuda, the only sea bounded purely by rotating ocean currents that form the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. The sargassum contained within this gyre is not the reason the US Virgin Islands’ Governor declared a state of emergency last year – with shorelines inundated and crucial water desalination systems impacted by the brown macroalgae. Rather, a new sargassum system has arisen further to the south that comes to life in the tropical Atlantic every spring and summer season, routinely growing to span an area that connects West Africa to the Gulf of Mexico and one that now even has an official name: the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt (GASB). Since the first unusually large summer bloom was observed in satellite imagery in 2011, the belt has increased, reaching alarming peaks in 2015 and 2018 when it extended for more than 8,850 kilometres and carried a wet biomass of more than 20 million metric tonnes in June 2018. In January 2023, another vast bloom of similar size was reported to be heading for Florida’s beaches, but as luck would have it, a whopping 75% of the behemoth mass died off just before reaching land, according to scientists from the University of South Florida’s Optical Oceanography Lab, narrowly avoiding mass havoc during the zenith of the tourism season. A close call… But what will happen next year, and is there an emerging ‘new normal’ to this creeping nightmare?

Floating barrier collecting seaweed – © iStock-Flavio Vallenari

So, what’s the deal with this stuff? Is it good, bad or just ugly for tourism’s piggy banks?

Firstly, what is it and what does it do? Sargassum is a genus of large brown algae (seaweed) belonging to the Sargassaceae family currently comprising over 300 species; however, only two – Sargassum fluitans and Sargassum natans – are holopelagic (never attaching to the seafloor) and these dominate the now two large-scale floating domains of the Atlantic, namely the Sargasso Sea and the GASB. Berry-like, gas-filled bladders keep the sargassum afloat while its totipotent cells allow the marine plant to reproduce asexually, growing anew from mere fragments of itself. These clever adaptations allow vast, free-floating mats to form at the sea’s surface, transforming an otherwise featureless realm of nutrient-stressed open water into vibrant habitats that support a treasure trove of marine life. For this reason, the Sargasso Sea has long been recognised as a biodiversity and productivity hot spot – a wondrous and magical realm that provides food, shelter and breeding habitats for countless creatures that have evolved alongside it. In this region of the North Atlantic, the sargassum is a critical and celebrated feature of the broader marine ecosystem, but outside of the Sargasso Sea’s current-driven forcefield, the seaweed’s reputation is one of dire destruction.

Beach full of sargassum algae

A kelpfish hiding in Sargassum uses these algae to blend in and hide from predators – © iStock-Joe Belanger.

Start-ups or escapees?

It is still unclear as to how the GASB began. Some scientists indicate that the sargassum from the Sargasso Sea began to escape eastwards as a result of shifts in usual wind and current patterns – specifically during the 2009–2010 extreme North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) anomaly, which allowed the seaweed to reach Gibraltar and subsequently be carried southwards by the Canary Current. From West Africa it purportedly drifted westwards into the tropical Atlantic, allowing a new regime to become established, now delivering swathes of unwelcome seaweed every spring and summer season to the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Other studies suggest that the GASB is a self-starting system dominated by a previously rare and genetically distinct form of S. natans, now encouraged to proliferate due to high-nutrient influxes out of the Amazon and Orinoco rivers following a significant uptake in cattle and soybean farming. Additional potential factors include dust storms and biomass burning originating in Africa that feed into Saharan dust clouds containing the fertilising nutrients iron, nitrogen and phosphorus, which are in turn blown by trade winds thousands of miles westwards. Nitrogen values present within the tissues of sargassum are indeed now reading 35% higher than samples taken three decades before. Add to this some strong upwelling currents off West Africa, optimal water surface temperatures and lower pH values due to ocean acidification (this counterintuitively encourages tissue growth in macroalgae) and there exist some fairly suspicious agents of change acting to unleash ecosystem chaos.

Boat surrounded by Sargassum seaweed at Tulum Beach, Mexico – © iStock-Marc Bruxelle

iStock-shakzu

Smothered by seaweed

Rather than moving as one gargantuan floating blanket of seaweed, the GASB presents as many separate island-like masses that can stretch for miles, inundating some shorelines, while skipping others. Once in shallow coastal waters, the dense seaweed carpets can smother coral reefs and prevent sunlight from reaching critical seagrass habitats – all bad news for biodiversity and fragile food chains, while also clogging harbours and waterways, ensnaring fishing boats and gear, and blocking pumping station intakes. Washed up on shorelines – up to 6 feet deep in places – the dying sargassum releases noxious ‘rotten-egg’ hydrogen sulphide vapours, which are a real killjoy for beachgoers and local economies alike. Turtles are also hard hit by the invasion as the seaweed’s arrival coincides with their nesting season, the heavy beasts being forced to labour through mountains of tangled, rotting matter to find clear beach sand in which to lay eggs, not to mention the difficulties hatchlings face when trying to return to the sea. In clearing the mountains of mess from beaches, heavy equipment can crush turtle nests while costing millions to operate at the scale required to remove such quantities. Furthermore, the mats of seaweed themselves have become hazardous quagmires accumulating plastic debris, pollutants and harmful bacteria, making handling and decomposing the endless mess highly complex. From tourism and fishing industries to human health, the impacts of these unprecedented blooms are far-reaching. Unlike in the Sargasso Sea, where the gyre sustains and restrains the seaweed, the sweeping sargassum of the GASB wreaks total havoc on all.

Copyright López Miranda JL, Celis LB, Estévez M, Chávez V, van Tussenbroek BI, Uribe-Martínez A, Cuevas E, Rosillo Pantoja I, Masia L, Cauich-Kantun C and Silva R, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What to do with all that junk

When one million tonnes of seaweed washed up onto Mexico’s 2019 summer season beaches it called for some solution-space action. In fact, the recent episodic blooms have driven many private and government-funded operations in affected regions to transform the pestilential plague into commercial profit. Economic uses that have made it to the R&D cutting table include: extracting sodium alginate for use in the pharmaceutical and beauty industry – it is used as a thickening agent, the market for which is projected to be worth $1 billion in 2025; as a biofertiliser in crop production; as a component in livestock feed; and as a corrosion inhibitor for oil and gas pipelines. One innovative team from the US-based National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) is exploring ways of utilising both the enormous wood waste left behind among Caribbean Island landfills post hurricane season and the swathes of sargassum now choking their beaches. Their research team is proposing using these raw materials to create both a sustainable aviation fuel and, with the leftover material from that fermentation process, graphite – to be used in electric car batteries! Many of these ideas are in the exploratory phase, but some researchers are cautioning: those proposals with designs for the food and livestock industry must strongly consider the high concentrations of heavy metals – arsenic, mercury and germanium – present in many of the sargassum samples studied. Limiting uses of sargassum to non-consumable options would be wise, certainly until this potential health risk is better understood and purification processes can be built to filter out such contaminants.

© iStock-eugenesergeev

Workers are removing Sargassum seaweed from the beach at Playa Paraiso with a Barber Surf Rake Beach Cleaner – © iStock-Marc Bruxelle

Message in a bottle

Though sargassum seems to be loving life in the central Atlantic, it doesn’t appear to like it too hot. Could warming waters be the reason we see mass die-offs? If so, relying on climate change to mitigate these unwanted blooms is a poor bet, as larger-scale shifts in ocean currents will likely continue to serve up unpredictable impacts over time, such as the bringing up of more cold, nutrient-dense waters from the deep, as seen off West Africa. It does appear that the world will just have to take it as it comes, when it comes.

On one side of the coin, sargassum forms an ecosystem of ineffable importance to the global marine environment; on the other, it is a creeping shroud of destruction, one that may continue to grow more potent as our climate systems destabilise and pollution continues to threaten all. The message remains clear and ever louder: cease treating our oceans and airways as dumping grounds for our waste; respect the sensitivity of natural systems by greatly curtailing impacts from industrial activities; and be prepared for the many days of reckoning should we not heed such warnings. The sargassum explosion of the GASB is not an enemy, it is an alarm bell. The real question is: how much louder do they need to get?

The continued presence of sargassum seaweed on the beaches of Mexico continues is of concern to many travelers as it blankets the shoreline. – © iStock-Samantha Haebich

The sensational and sensitive Sargasso Sea

As their expeditions ventured across the North Atlantic, Columbus and his crew were haunted by the sargassum, encountering perpetual rafts of cursed seaweed while also suffering the effects of hot, windless climes in the gyre’s centre. Desperate sailors, on the edge of mutiny and madness, imagined the seaweed’s roots extending down to the many wrecks surely lying on the seafloor below. In his acclaimed novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Jules Verne pens: ‘Such was the region the Nautilus was now visiting, a perfect meadow, a close carpet of seaweed, fucus, and tropical berries, so thick and so compact that the stern of a vessel could hardly tear its way through it.’ Today, the same phenomenon has been coined the ‘golden floating rainforest of the ocean’ by international marine explorer and conservationist Dr Sylvia Earle, who understands, as many now do, the profoundly important role it plays within the broader marine ecosystem.

The Sargasso Sea, whose depths range from the surface coral reefs of Bermuda to abyssal plains at 4,500 metres, is characterised by clear, oligotrophic waters atop of which floats this otherworldly sea forest. The sargassum mats create infrastructure in a featureless open-ocean environment – not only serving as shelter, but as critical feeding, spawning and nursery grounds for a gamut of species, many of which are threatened and endangered. It also functions as a welcoming corridor for migrating sharks, rays and up to 30 cetacean species and is the only breeding location for the highly threatened American and European eels. Flying fish are an important component of the marine food web and rely heavily upon the safety and structure of the mats in which to lay their bubble nests. Larger predatory pelagics such as tuna, wahoo, billfish and dolphinfish all hunt under the floating mats while young turtles survive their ‘lost years’ before returning to nesting beaches to breed. Seabird densities above the mats are over 40% greater than in areas without sargassum. The floating sargassum ecosystem has been around long enough for 10 specialised, endemic species to have arisen that are highly adapted to a camouflaged life among the fronds, the sargassum fish (Histrio histrio) being the classic example. The economic value of this biodiversity hot spot and the expanded impacts it has on economies all around the North Atlantic are vast, with commercial fishery revenues alone estimated at $100 million per year, notwithstanding local fishery and tourism industry estimates. And like the actual rainforests of the world, this sea forest plays a disproportionately large role in global ocean carbon sequestration, and, as we know, this is critical in the fight against climate change.

Located in one of the busiest oceans, the Sargasso Sea, which holds an estimated 10 million tonnes of seaweed (70% carbon by dry weight), is under serious threat from every angle perceivable: ships churning up the mats and destabilising microhabitats; ever-increasing concentrations of plastic and chemical pollution from vessels and land-based sources; boat strikes; rampant overfishing; entanglement of wildlife in plastic debris trapped within the mats; seabed mining; and harvesting of the sargassum itself for use across industries from fertilisers and biofuels to food, beauty and construction. Located beyond the jurisdiction of any one government, the Sargasso Sea is highly vulnerable and benefits from little protection, which thankfully prompted the government of Bermuda and its allies to form the Sargasso Sea Alliance in 2010 aimed at stimulating protective management protocols.

https://www.sargassoseacommission.org/storage/documents/SargassoBrochure.FIN.pdf

A potential pathogen storm in the sargassum plastisphere!

A new web of the seaweed’s unintended sorcery has recently been unveiled by a microscope-wielding team at Florida Atlantic University that focused upon the microbial community dwelling within the sargassum’s web of matter – a mixture of sea life and entangled plastic pollution (this plastic debris is so omnipresent in the marine environment it now forms its own ecosystem known as the ‘plastisphere’). Bacteria within the genus Vibrio are ubiquitous in aquatic environments, some famous species being responsible for serious human health threats such as cholera and flesh-eating disease, but there now appears to be a subset of such life forms that are strongly attracted to plastic waste in particular, evolving ways to adhere to its slippery surfaces. Among the genes retained and selected by these plastic-loving strains are those that cause leaky-gut syndrome, revealing the story’s truly terrible twist: sea life inadvertently consuming the microplastics upon which these bacteria are living could ostensibly suffer diarrhoea, releasing added nitrogen and phosphate into the water to act as fertiliser for the sargassum and other organisms. These tangled mats of seaweed and plastic waste could well represent novel breeding grounds for fast-evolving, disease-causing microbes that indirectly enhance the growth of the whole ecosystem!

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20230622-what-is-causing-the-atlantics-seaweed-blobs

Further Links

https://www.sargassoseacommission.org/publications-a-news/atlantic-sargassum-belt

https://www.sargassoseacommission.org/sargasso-sea/economic-value