HMS recounts an excerpt from his account, as published in the latest edition of the global best-seller Heavy Weather Sailing, of the occasion when on passage from Newport to Killybegs, he and a flotilla of RIBs faced a westerly gale and 30ft seas.

The forecast was not good for leaving Newport, County Mayo – an initially ‘on-the-nose’ north-westerly, with a wind strength of force 7, increasing later. After some consideration, we decided to set out with the intention of reaching Killybegs, some 80nm to the north, but on the understanding that we would return to port if the conditions became too hazardous.

The Severn-class lifeboat that led the RIB flotilla out of Newport and down the waterway to the entrance of Achill Sound dwarfed our little ‘ships’ as we plunged along behind. The wind was fairly whipping off the land now, and the spray from the agitated waters of the lifeboat’s wake flew horizontally across our craft. Even here, in sheltered waters, the scene about us was already menacing and did not bode well for the day ahead.

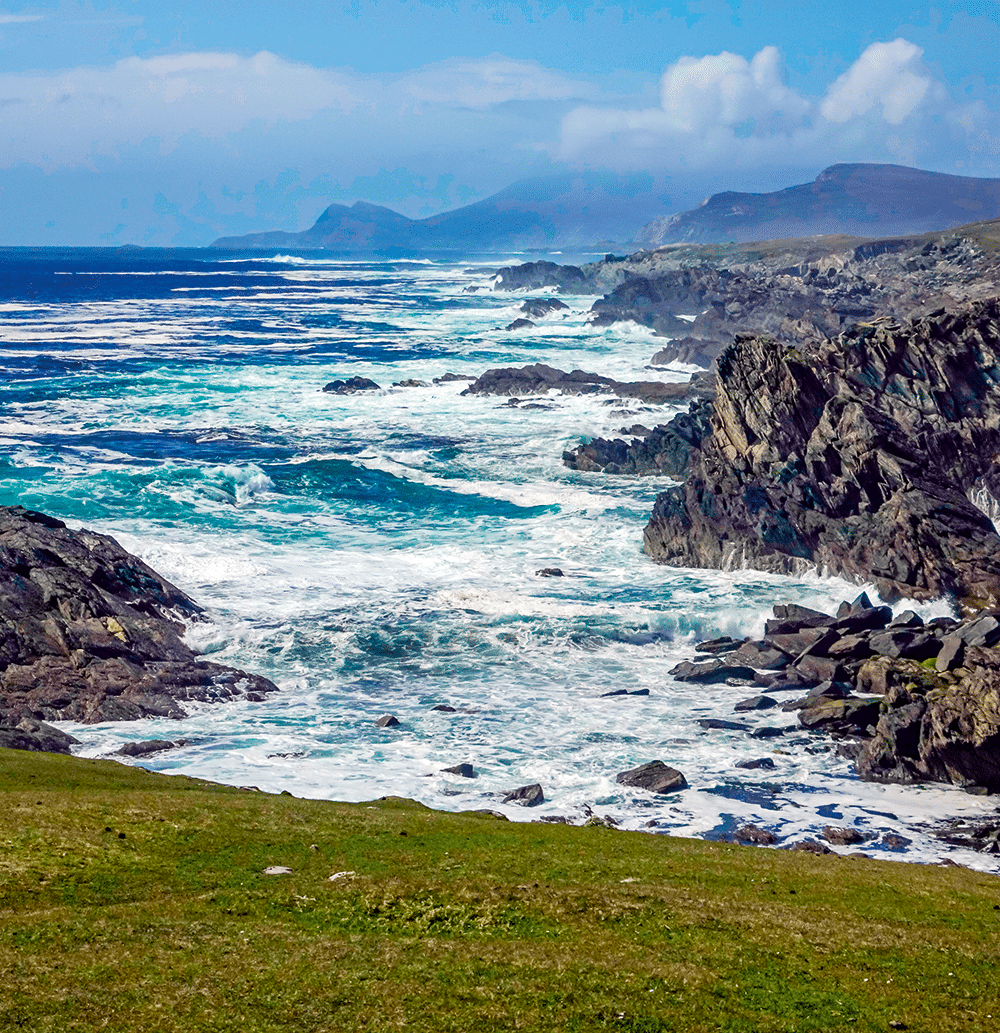

Rough ocean with waves crashing against cliffs in Co. Clare, Ireland

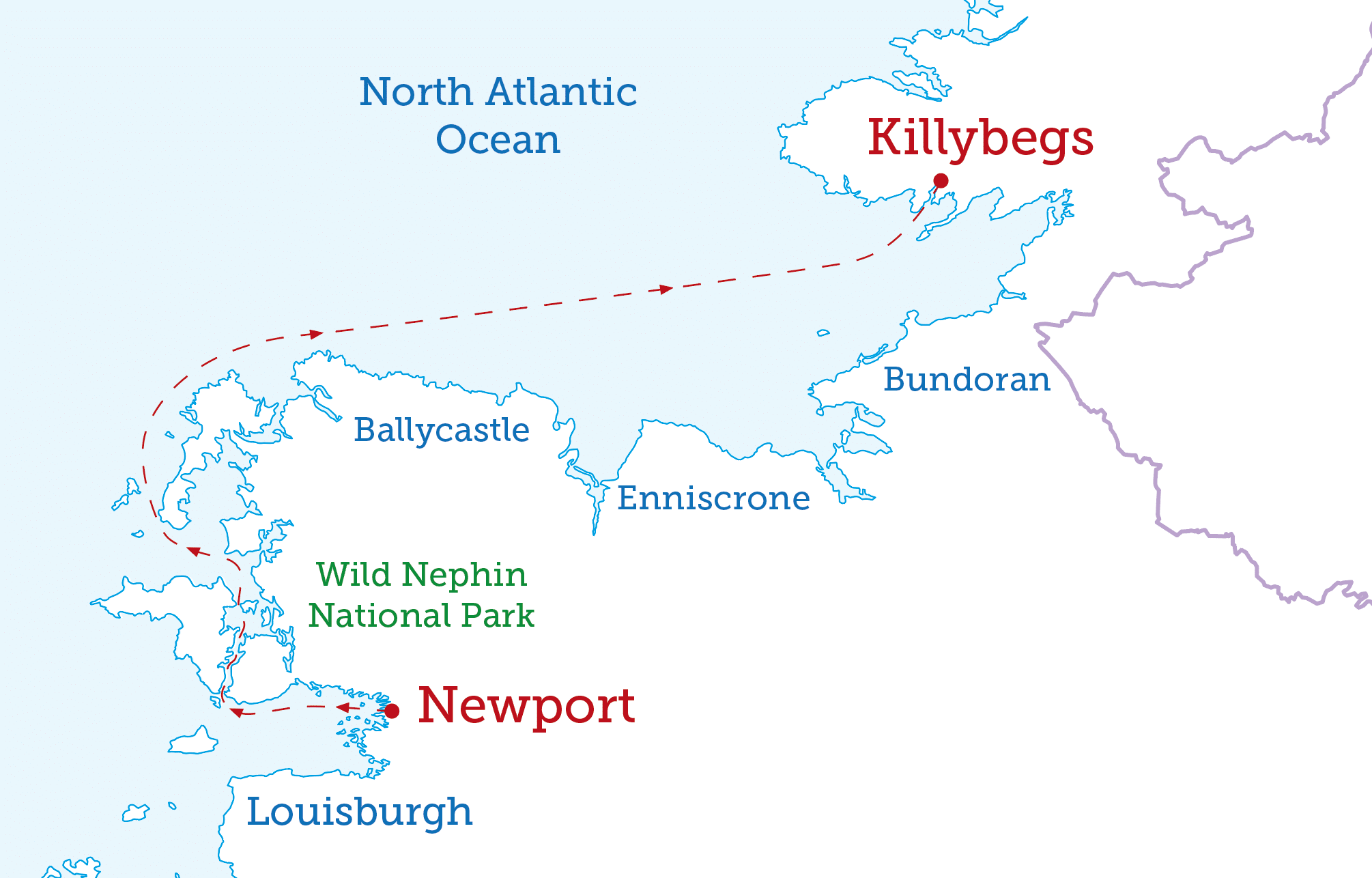

Route Map: Starting at Newport and finishing at Killybegs.

Bows to seaward

Soon the lifeboat cox radioed his goodbyes and set course for home at Clew Bay, and we were left to our own devices. We made our way along the winding sound before joining the rest of the fleet waiting with idling engines in the inshore waters of Blacksod Bay. It was touch and go as to whether the big boats would clear under the road bridge, but this tricky inshore route cut off a good 32km of potentially difficult and exposed waters around Achill Head, and we were all very grateful for the pilotage provided by our RNLI friends that had made it possible.

Now all safely mustered on the seaward side of the bridge, everyone busily set about ensuring their kit was fit, lashed down and ready for sea. It would be our last chance, for once out into the open ocean, the likelihood of being able to stop to secure gear would be remote.

White Cliffs fo Ashleam. © Bo Sheringa shutterstock.

We all tried to stay together as a group in the rough conditions that we encountered in the exposed fetch beyond the bridge, and I was amazed at just how well our little 6.5m Redbay RIB was coping. Some RIBs of this size, it has to be said, would no doubt have been throwing their heads wildly in such close-coupled steep seas, but not ours. She ran astonishingly level and, because of this, maintained a speed that justified leading the flotilla.

As we met the waters between the heads of Inishbiggle and nearby Bunacurry, we faced the true effects of the north-westerly fetch running directly in from the northern Atlantic. Adding to this was the concentration of tidal stream through the narrow passages that caused unusually high seas to pile in relentlessly at both Annagh and Inishbiggle. We powered on to meet the first of the big seas. It is always difficult to judge the height of waves in these situations, but suffice to say they were easily able to accommodate the full length of the 10m RIB running off our starboard side, as she climbed to their summits.

This Tornado outboard RIB with its crew of five shows immense stability amid the heavy seas. Note the relaxed nature of this RNLI lifeboat team taking part in the event.

Breaking crests and heaping seas

Icy spray smacked against our screen, running in torrents down the glass and momentarily obscuring any clear forward vision. Screen wipers would have helped, but we were still very glad of the cuddy cabin, as our weather side was taking a real hammering from the driving rain and spray.

Waves crash at Inisherin, Achill Island, Ireland. © Tony Conion shutterstock

To add to the difficulties of forward vision, I had to crouch over the wheel and crane my neck to get a proper view of each sea as we began to climb the face. Applying the correct amount of power was vital in order to maintain good steerage and ensure that we negotiated the crests of these waves comfortably. Of course, the bigger the wave, the bigger the trough on the other side, and the slide down into some of these chasms was sometimes nothing short of breathtaking. By now, the size of the seas frequently required the use of reverse power to slow our descent. Surfing too wildly would have resulted in the boat suffering an unwelcome ‘stuffing’, i.e. she could have smacked the bow into the wave beyond the trough so firmly that a wall of green water would have come over the bow and the boat would have stopped and lost steerage way. Such an incident would have immediately compromised our own boat’s security as well as the safety of any other members of the flotilla who might have come to provide assistance. All 16 RIBs had to keep moving.

With the Stag Rocks in the background, a big sea sweeps across the path of one of the RIBs as it crests a wave.

Into open water

We pushed on out to the open sea beyond the complicated area of tide and overfalls. Mind you, we didn’t really have a choice: turning round was not an option as it would have put all the boats at a very real risk of capsize. Running as a pack, the flotilla continued to remain tightly grouped all the way out to the land west of Belmullet. Every now and then I would glance astern, much to the annoyance of my navigator, Jan Falkowski, who quite rightly reminded me that it was my job to look ahead. ‘Never mind what’s going on behind, we’ll take care of that!’ he shouted. He was right, of course, for just a momentary lapse of concentration could have resulted in a breaking sea catching the boat unawares. As it happened, moments after he shouted at me, I failed to steer square to a very steep sea, and as we ran up its face, the crest curled and burst down from above onto the starboard side of the cabin – streaming down the canopy and on to the rear deck in a cascade of freezing water. Thankfully, due to our RIB’s extraordinary lateral stability, we suffered no harm – but it was a tense moment nonetheless. Tom, my son, who was in his teens at the time, and Jan Falkowski, former SAS reservist and navigator on this trip, remained cool amid the commotion, but I could tell by the hard-done-by look on his face that Tom really wanted to be behind the wheel! We pushed on as we had to, although, as later weather reports confirmed, the wind in our region was by now touching force 8.

Kildavnet Castle located near Achill Sound village.

© Davide Savio Shutterstock.

With the seas now on our quarter, we were able to push along at a surprisingly good 17 knots. One moment we would be climbing dark-grey ramparts of water that occasionally replaced our view of the sky ahead before surfing at even greater speed down their long sides into the deep troughs below. But as we edged further offshore to maintain our course, the seas began to lengthen to a more typical ocean-type swell. This sea state was less dangerous, and although maintaining visual contact with our buddy boats continued to be difficult, it was apparent that many of the RIBs were now getting into their stride.

The small, outboard-powered RIBs often fared better than their larger diesel-powered counterparts. This is a Ribcraft 5.85m.

Credit where credit’s due

All the boats and engine systems fared remarkably well that day, with no breakdowns. When talking to the crews and watching with interest how the RIBs performed in these sea states, one thing became obvious: the smaller boats very often had the advantage, with their high degree of manoeuvrability and quick acceleration proving very successful in the near-gale conditions. The big RIBs, especially those fitted with turbocharged diesel engines, were disadvantaged by the throttle response times and proved more difficult ‘to place’ in the difficult seas. The little RIBs were nippy, weaved a safe course and proved nimble enough to dodge the big ‘curlers’.

Most of the Round Ireland RIBs were open craft, and we were very glad of the protection the soft-top cabin to the Redbay 6.5m gave us. Without it, the amount of flying water would have been difficult to deal with, so the protection that it gave was a major safety factor, as well as reducing fatigue caused by the wind and elements.

Every one of our 17-strong RIB flotilla that day made the sanctuary of Killybegs Harbour safely. It may have been a very long and arduous passage, but the inherent abilities of these well-found craft and their engine systems, as well as their stalwart crews, were undeniable. This was a memorable passage indeed, and part of an extraordinary voyage that will be remembered no doubt by everyone who took part.

Having circumnavigated Scotland, Britain and Ireland, in my judgement, taking a small boat around Ireland constitutes the greatest adventure of them all. Though I wouldn’t recommend going in search of heavy seas or purposely seeking out a gale of wind, taking on a challenge of this type invariably involves meeting inclement weather and testing conditions. So, it’s all about having the necessary knowledge and being adequately prepared. If, in particular, you take the time to give attention to the latter, there is great reward and, without doubt, lifelong memories to be had.

Heavy Weather Sailing, 8th Edition

by Martin Thomas and Peter Bruce

Heavy Weather Sailing is the definitive book for both amateur and professional crews of any type contemplating voyages offshore anywhere in the world. This new edition includes updated thinking on a variety of aspects of heavy-weather handling, and recent heavy-weather experiences from around the world.

With this latest edition featuring a foreword written by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, for over 50 years now, Heavy Weather Sailing has been regarded as the ultimate international authority on surviving storms at sea aboard sailing and motor vessels. Former Commodore of the Ocean Cruising Club Martin Thomas also brings together a wealth of expert advice from many of the great sailors of the present, including fresh accounts of yachts overtaken by extreme weather from the likes of Ewan Southby-Tailyour, Alex Whitworth and Dag Pike through to Larry and Lin Pardey, Matt Sheahan and Andrew Claughton. For powered craft, special contributions are also made by Frank Kowalski and Hugo Montgomery-Swan.

The book’s expert advice section has been updated in line with current thinking, with major new additions tackling preventing or coping with lightning strikes, navigating in heavy weather with both paper and electronic charts, the choice and use of tenders in severe weather and special problems faced by the new generation of foiled cruising boats. For the first time, the book also covers the unique challenges presented by weather in high latitudes, with more yachts crossing the Drake Passage and attempting the Northwest Passage. These revisions ensure that Heavy Weather Sailing is as relevant, useful and instructive for today’s sailor venturing offshore as it ever was.

This edition is the definitive book for crews of any size, whether racing or cruising. It gives a clear message regarding the preparations required and the tactics to consider when conditions become highly testing or even extreme.

Joint author Martin Thomas is currently the Vice-Commodore of the Royal London Yacht Club. He was previously the Watch Officer on board the sail training schooner Sir Winston Churchill. A distinguished surgeon, he has written on the topics of emergencies at sea and medical treatment for yachtsmen. Martin Thomas’s fellow author, Peter Bruce, served in the Royal Navy for many years and continues to spend much time at sea, cruising, researching his pilot books or racing. Bruce is one of the top Corinthian skippers in the world, has twice been part of Britain’s winning Admiral’s Cup team and has taken part with distinction in most Fastnet races since his first in 1961.

Heavy Weather Sailing provides essential reading for all those seeking to undertake offshore passage making, be they sailors or powerboaters.

Published by Adlard Coles at £39.99.

For further information see www.adlardcolesnautical.wordpress.com and/or www.bloomsbury.com.