Thunder Child II: Inside the world of extreme endurance powerboating

An exclusive interview with Nick Ogden, Team Principal of 54 Knots Endurance Team.

Home / Features / Adventures

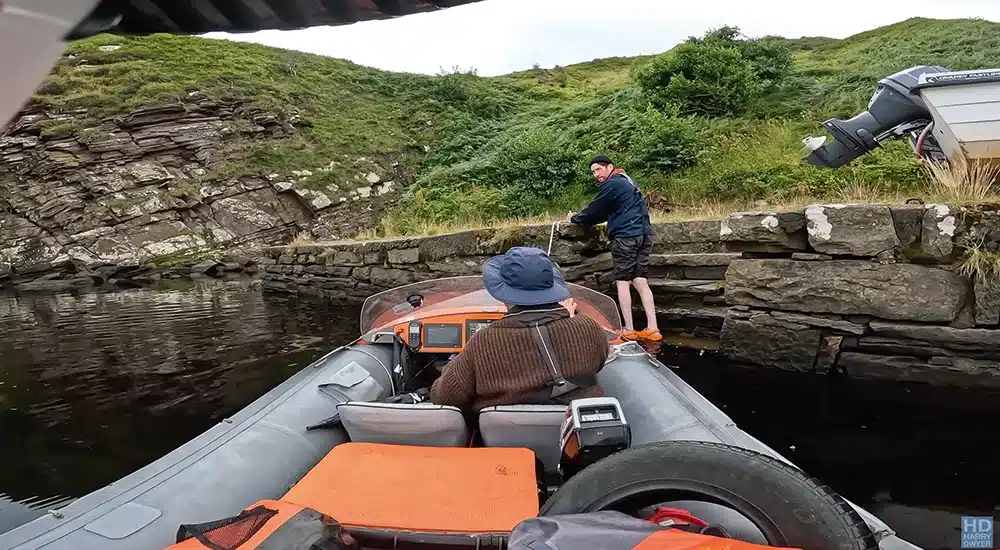

In this exclusive interview with HMS, videographer Harry Dwyer relates the extraordinary highlights of circumnavigating Britain over a five-year period aboard his trusty, second-hand, vintage 4m Avon Searider RIB, Goodwin.

I was in London at my small workshop on the Thames and was given my old Avon Searider for ‘free’ in exchange for my help to carve out expanding foam during work to my friend’s liveaboard lightship. The old RIB needed a lot of work, but eventually I had a solid running boat.

I didn’t know anything about boating really, but after a few trips up and down the Thames, I decided it was time to take her on a longer adventure. I’d been filming the fixing and fit-out of the boat for YouTube and I may have mentioned that we could take the boat, now called Goodwin, around the coastline of the UK when all the work was complete. That said, I don’t think I really ever intended on going all the way round! But after experiencing the muddy Thames, I just wanted to get into some clearer, silt-free water and perhaps land on the odd pirate cove in the process. In addition, the idea of camping along the way just seemed too much of a fun opportunity to miss out on.

I think I also have a keen interest in seeing what’s around the next corner. So when travelling along the coast, that’s often a big factor, something that drives me along. I’m intrigued to see – to discover – what’s around the next headland.

My ‘next-door neighbour’ at my workshop runs the London Powerboat School. He had originally spotted the old Searider being put up for sale by the PLA [Port of London Authority], who’d used it as their work boat down at Gravesend. He really knows about boats, does Bill, and he understood the little craft’s impeccable seakeeping qualities. My friend with the lightship was looking for a tender to use on the back of his riveted iron-hulled vessel, and so Bill from the powerboat school suggested it would be a perfect boat for hoisting onto its deck, which is where it lived – until I inherited it.

The old side-by-side seating set-up is unusual these days, as folk appreciate that jockey seats are a lot more comfortable when riding the waves. But then again, in my view, there’s still nothing like ‘side-by-side’ for that magical ‘road trip adventure’ feel.

The boat had a critical engine fault, which I had to fix first. Then I decided to go through the whole boat and give it an overhaul. When I started, I didn’t want to spend any money on the boat, so I bought the cheapest components and did all the work myself. I have since learned the importance of 316 stainless steel and buying high-quality stuff rather than the cheapest ‘waterproof’ switches from eBay.

When I began this whole adventure, I truly had no idea that the size of a boat affected its sea-kindly nature and played such a big part in terms of overall comfort underway. I assumed a small boat would mean less room but never realised that it’s directly proportional to the way the boat rides over the chop. The drawbacks of the length of the boat, the height of the bow and the low seating position quickly made themselves apparent. That said, there are sea conditions where having a small boat makes life a lot easier. In addition, a shallow draught means we don’t run aground so easily, and it’s easy to get onto the trailer and store. It’s also easier to tow, of course. Another big advantage is that it doesn’t use much fuel either. We normally average 2 miles per litre of petrol.

Launching on the Thames is a tricky affair as you’re at the mercy of the tide sweeping you away when the engine dies. So we started with short trips to the pub upriver and slowly, bit by bit, made longer expeditions. Having said that, Goodwin was, and still is, a ‘work in progress’, so it was never really ready for the trip. I pretty much fix, upgrade or replace something after every trip, as and when improvements are required. I’ve learned that to a certain degree, a boat is probably never completely ready for a trip like this, so at some point it’s better just to set off and fix it later! Often I worry about stuff that isn’t really an issue once you’re underway and out to sea. The ‘prepper’ mentality in me makes me want to get everything perfect, but in reality, I just need the engine to run and a working GPS. Oh, and some good snacks! As you know, we did the trip in bite-size legs, so it was relatively easy to test en route and worry about fixing something later upon reaching our destination. I’ve just rewelded the A-frame again, this time with gussets. It broke on the last trip and I could hear the clanking and grinding of metal as we bounced from crest to crest. Luckily, it was only one upright that sheared off. I had welded the other side previously, which made the repaired section all the stronger.

The other big factor in preparing for each trip is working out who is coming with me. I’ve been very fortunate to have some long-suffering friends who have put up with the slamming through the waves without too much complaint. Sharing the journey with an old friend makes for a really fun adventure, and I don’t think I’d ever want to go it alone. I’m not a solo sailor.

I get a lot of comments about the low frequency of my YouTube videos and I’m forever wishing I was out on the water, particularly when the conditions are perfect for my tiny Searider. Sometimes I’ve only managed to get a few trips on the water in a year (partly because I spent too much time in boatyards getting carried away with upgrades!). I even found myself not enjoying calm, sunny days at home because I knew that it would be great boating weather. But now, after the therapy and medication, I’m coping a little bit better!

Making these videos has been a satisfying personal project and a good departure from my normal freelance video work, but as the videos have become longer, the editing process has started taking up too much of my time. I’ve been concentrating on completing the circumnavigation this year and work has taken a bit of a back seat, much to the alarm of my partner. But I plan to get back in the work zone – if for no other reason than to stop myself going bust.

I also spent a lot of time scouring Google Maps, planning the possible routes for each leg. Getting familiar with the upcoming coastline and possible stop-offs is essential and serves as good mental preparation. Every available idle moment would also be an opportunity to check windy.com to see if the weather was either improving or deteriorating. Generally speaking, I certainly worry more about the logistics of an upcoming trip than it would appear in my videos. But once I’m out on the boat, all the worry evaporates, and I’m there once more, back ‘in the moment’.

The Scilly Isles were somewhere I had never been until I voyaged there in the boat. They are an absolutely incredible part of the British Isles and it’s hard to believe, particularly on a glorious summer’s day, that they’re actually part of our native shores. There are hundreds of wild islands and turquoise waters – the Scillies are like the Caribbean. And hardly any roads either, which is so nice. It’s representative of a past era. I can’t understand why I’ve never been to Scilly before! The Western Highlands and islands of Scotland are great RIB territory, of course – definitely somewhere that I’d like to spend more time exploring. Plus, there are many hidden gems we’ve found in seemingly less exotic pockets of the coastline, including Piel Island in Barrow-in-Furness, Port Quin in Cornwall, the River Stour … I could probably bore you for hours!

Prior to setting off, the wonderful friendliness and hospitality of locals was not something I’d really considered would ultimately play such a major and welcome part of the entire experience. Local knowledge and an occasional lift to the petrol station ended up being essential to help us on our way, and it’s been great to feature some brilliant local people in the videos I’ve made. The process of staring at charts and wondering when to depart based on the previous experiences of others via a blog represents a poor second to simply chatting to someone who knows the area well and who often just gives you the confidence to go for it! We have met lovely people all around the British Isles who have gone far out of their way to help and be supportive. I think having a ridiculously small boat makes people feel a bit sorry for you and they perhaps go the extra mile.

The matter of weather has been critical throughout, and the more remote legs of the journey, not surprisingly, made getting the planning right all the more critical. It’s hard to tell if the weather will be right for a passage 10 days in advance, and sometimes we had no choice but to go in less-than-ideal conditions. I have spent a great deal of my time looking at windy.com and other weather websites and often found myself willing for things to improve in the hope that we get a run of good weather. Sometimes, of course, the weather proves stubborn and then all the willing in the world is insufficient to cause the weather to shift in the right direction.

Filming too, when it’s rainy, is a challenge, and it’s hard to capture the experience properly when the conditions are grey and the light is drab. A certain amount of precipitation is good, but there is a limit! In true English style, we carry a brolly, but the drone doesn’t really work in the rain. Nevertheless, the drone proved without question to be a vital tool in our being able to capture the landscape in its true glory. I’ve flown drones for years in connection with my work and knew from the get-go just how much this versatile technology would be perfect to record our antics at sea. But flying over water doesn’t come without its risks. We have so far destroyed no fewer than three drones. To lose a drone hurts, of course, but to lose the footage is even more frustrating. It’s the imagery that got away – like the shoot we did at dusk with Goodwin beached on the shore of a tiny, castled island in a Scottish loch, our underwater lights shining like comet tails through the cold waters … Potential award-winning cinematography, though lost to the depths, nonetheless remains etched into my mind forever.

We joke about PTSD thanks to the arduous nature of some of the legs endured, but the true terror of those big seas around Cape Wrath will perhaps leave their mark on my co-driver Charlie and me for as long as we live and breathe. On another occasion, I remember taking a few weeks to recover after I broke my toe on a rock after making a beach landing amidst a squall that we were trying to gain shelter from. The plan didn’t work as hoped as Goodwin was pitching wildly at anchor off the beach, so we ended up aborting and swimming out to her in order to get going before she ended up on the rocks! There’s something scary, entirely sobering, about being at the mercy of the sea. When the weather changes, the clear blue sea becomes dark, intimidating, threatening. Sitting inches from its restless surface aboard the likes of Goodwin, it’s easy for one’s morale to wither as gallons of freezing water hit you repeatedly in the face and you’re slammed into the waves, one after the other. That said, doing the trip in stages over an extended time period has given us the recovery time and opportunity to renew our enthusiasm for the next leg on the chart.

But other than crippling wind and sunburn, there haven’t really been any significant physical impacts on our bodies to speak of. Although more often than not we were having to pound through miles of chop, I’ve personally never had to contend with the discomfort of back pain. If anything, I feel all the fitter for the experience. Fortunately, I don’t get seasick, which is a great blessing, of course. In fact, erecting the tent and dragging all the gear in and out of the boat was probably more tiring, more wearisome, than most things encountered on the voyage. Getting an early night in the tent, though, was as essential to combatting fatigue as was trying to limit one’s wine intake! There’s always the next day, the next early morning to think about on a mission such as this. Late nights and wine toasting don’t make for a good recipe when it comes to facing the elements and a long haul.

Levelling with you, I’m not sure I would do it again. I started it and I wanted to finish it, but if I’d have known what was involved, in truth, I never would have undertaken it. But I’m very glad that I did, all the same. They say ‘ignorance is bliss’, and I guess, to some extent, I tricked myself into doing it through nothing more than a lack of knowledge!

If I was going to do it again, however, I’d probably want to do it in something somewhat larger than a 4m Avon, something that would make the chop less hard-going, and perhaps a boat with a cabin and a couple of berths too, so you could just drop anchor and get your head down. Mind you, though that would be the easy option, it might not be half as entertaining! (Originally, I was thinking about fitting a couple of makeshift beds in Goodwin, but you won’t be surprised to learn that there wasn’t the space! As a result, the videos made feature lots of footage of us making camp ashore.)

It’s going to take longer than you expect, so make plenty of time in your schedule. Besides, in reality, you want to take your time. With this in mind, try not to pick the quickest or most direct route by cutting off those big bays and simply going from point to point. Instead, forget about how many miles there are still to go, stop off, explore and get to experience as much as you can along the way. I still regret the places that we didn’t call in at. But then again, trying to visit everywhere is virtually impossible, of course, and would take forever. All the same, especially when the going is favourable, resist being tempted to cover as much ground as possible. Rather, savour as much of the coast as you can.

We completed our circumnavigation in legs, in stages. This also assisted in the making of the videos and our being able to manage all the camera gear we needed to operate along the way. But once you’re in the swing of it and you get into a rhythm, things naturally become easier. Some of the best legs were the longer ones, where waking up in the tent and paddling out to the boat to make some miles before breakfast seemed like the normal daily routine. That said, if you get fed up, there’s no harm in stopping and coming back to it. It all becomes a bit of a waste to mindlessly flog on, powering your way through no matter what, once you’ve become numb to the beauty of what’s around you.

There’s nothing like that feeling you get upon having completed a trip successfully. After all the planning that goes into the route, deciding where to camp, the logistics, the handling of the drone, the capturing of the footage, it rarely goes completely to plan, but getting the boat back safely on the trailer again at the end of a voyage certainly makes for a very peaceful night’s sleep.

Nonetheless, rounding Cape Wrath, I have to say, really made us question what we were doing. We were both terrified and honestly thought we might die. ‘Why the hell are we doing this?’ we asked ourselves. Charlie is never normally scared, although I tend to be quite a lot of the time. We’d met a viewer further south who said: ‘You’ve not come this far to go through the canal, you’re going around the top, right?’ That stuck with me, so we did it, with Cape Wrath becoming our personal Cape Horn. In hindsight we were OK, but we’d never been in seas like it. Plus, I had put a bigger, faster prop on, which was the wrong choice, because we then struggled to get the traction we needed up the face of those huge, steep seas. As I’ve likely conveyed sufficiently already, it was nightmarish stuff, and the boat took a real pasting in the process, suffering damage as a result of becoming airborne too many times as she crested the swells.

Since our experience of rounding Cape Wrath, we’ve been around Peterhead, and upon approaching some large standing waves in the overfalls off the headland, my co-pilot Eddie enquired casually: ‘Is this doable?’ By then I knew it was and felt confident enough to slowly plough on through and over the waves, throttling back on the crests momentarily to prevent the prop from cavitating and the boat’s nose from flying. A lot of rough-water navigation is about real-life experience. It’s hard to explain because so much of it is about ‘feel’, and anyway, there’s only a certain amount you can learn from books or YouTube.

There’s something very tactile about a RIB’s tubes. You can jump on them, climb on them, sit on them, lie on them and, if you’re energetic, they’re good for climbing over when getting out of the water after a swim! They are also good for bumping into docks, pontoons and other boats. They turn a GRP hull into a very forgiving beast that everyone loves to have around. They pop back up again if swamped by a big sea, and as long as you have nice big scuppers, the water just floods straight out the back of them once underway. Small RIBs are nippy and fun, simple to launch and recover, straightforward to drive, and they can reach coves and hidden parts of the coastline that often remain inaccessible to many other craft.

I’d like to try some expeditions further afield – Venice could be nice, though we might have to dismantle or, better still, hinge the stern mast housing the thermal camera and radar dome in order to get under the city’s low bridges. Around a Greek island or two might be nice. Learning to scuba dive or waterski from Goodwin would be fun too. Perhaps crossing the English Channel – but then again, there’s still so much to explore closer to home. Around Ireland, maybe, or out to St Kilda. There are certainly plenty of options on the table – but first, Goodwin and I might just have a bit of a rest. Besides, at this present time, we don’t yet have hydraulic or fly-by-wire steering fitted to the boat, no autopilot system either, so I feel some non-essential upgrades are in order before seriously setting off again!

I was talking to someone at Honda PR and I had a 50hp on loan but they didn’t really get behind it properly and I needed more support and a manufacturer I could work with more closely. Suzuki stepped in with the current 50hp long shaft engine and enthusiasm for the project, along with servicing down with the guys at Ash Marine and they even paid for 250 scotch eggs at the finish line! I still have the original fire damaged 30hp engine but the trips with the Suzuki have been quieter, faster and it’s one less thing to worry about going wrong.

Follow Harry Dwyer’s Adventure on his YouTube channel

See the article in our Digital Edition

An exclusive interview with Nick Ogden, Team Principal of 54 Knots Endurance Team.

Trailer boating combines freedom, affordability and adventure, offering a flexible way to explore new waters while avoiding the costs and…

Jo Moon reports on New Wave Club's innovative membership model that's making boating accessible to all. From premium Sea-Doo jet…

Discover the latest motorboats, innovations, equipment, and refit expertise at boot 2026, the world’s leading boating showcase returning to Düsseldorf…