Mark Featherstone discusses the complex but fascinating subject of tides and their effect on even high-powered craft. By means of salty tales and some choice facts, Mark demonstrates that tides, like a lot of things in life it would appear, are all about timing.

‘Nae man can tether time or tide.’ So wrote Robbie Burns in his poem of 1790. With these words ringing in my ears while recently walking through a deserted airport terminal, I decided to walk on the travelator contrary to the direction it was seeking to take me in. Not surprisingly I went nowhere fast, and in case I needed to be reminded, my ‘tomfoolery’ emphasised just how much harder I had to walk in order to make headway against the travelator’s ever-moving black ‘tide’. Of course, on turning about, I fairly sped along, covering the ground swiftly with little or no effort required.

This simple experiment illustrated to me perfectly the tidal effects found throughout the oceans of the world, because for all intents and purposes, even though it may not always be observable, oceanic tidal movements are very much like that airport travelator, and can both help and hinder the mariner in equal measure. Sailing craft are particularly subject to this force, but even with a powerful motor vessel, the tide will have a direct bearing on (a) your speed over the ground, (b) your comfort and safety, and (c) your vessel’s fuel consumption. By perhaps just waiting a mere hour or two for the tide to change in your favour, you could score highly on all three points. On the face of it, it would appear to be a ‘no brainer’!

Use the tide to your advantage

Broadly speaking, there are two tides a day, 365 days a year, and every tide is slightly different, because each tidal movement is influenced by a multitude of unique factors. These include the position of the sun and the moon, barometric pressure, wind force and its direction, and all these are related to the topography of the coastline and the sea floor itself. When participating in the Round Britain RB4 RIB challenge of 2001 with HMS, our esteemed editor, we were covering over 200 nautical miles a day. Some of the passages represented 18-hour days, and hence we really got to experience the full measure of the ebbing and flooding tides. Every day it worked both against us and for us. We could rarely alter our passage to account for the tides, but understanding them meant we could more accurately calculate the ETA at each day’s final destination and what we could expect along the way.

The pictures above and below of Charlestown Harbour at low tide and high tide show how unrecognisable the same harbour can be depending on the state of the tide.

Beautiful sunny summers day at Charlestown Harbour near St Austell Cornwall England UK Europe

Tidal flow

Planning your passage around tidal streams is good seamanship, and using them to your advantage makes the difference between an efficient, easier-going voyage and a relentless slog that everyone aboard has to endure through gritted teeth. Admiralty Tidal Stream Atlases and Almanacs show the tidal streams hour by hour and display ‘the set’ or direction of the streams along with their ‘rate’ or speed. While I carry paper copies on board my boat, there are some very useful downloadable and inexpensive apps available (see boxout and Paul Glatzel’s special app feature in Issue 178 of PBR), in addition to the electronic cartography produced by the likes of C-MAP and Navionics.

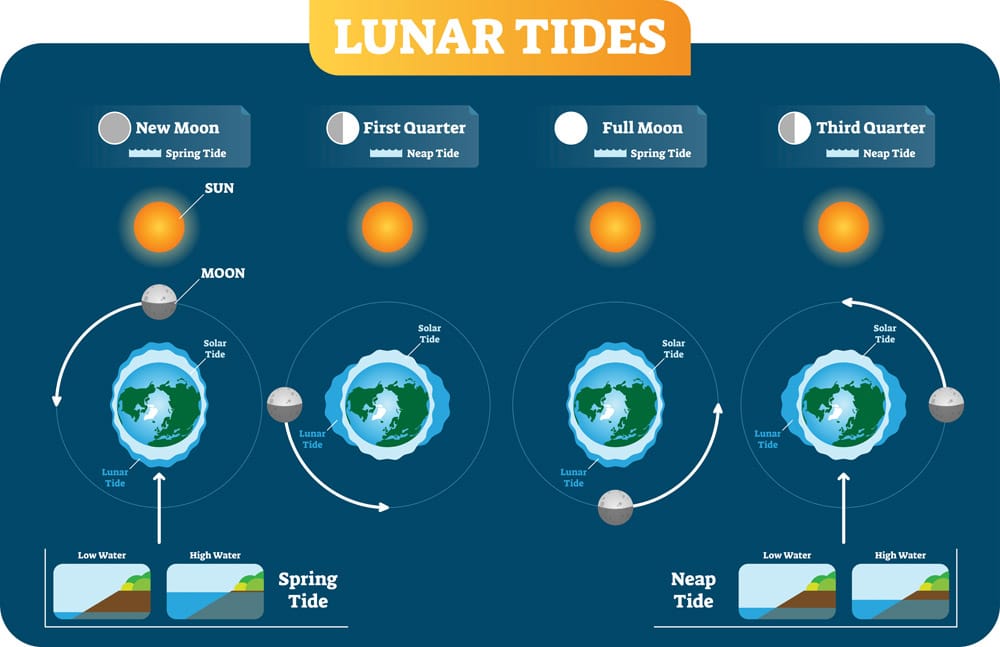

Many people are unaware that at different points within a tide’s cycle, the rate of flow changes quite dramatically. For example, during the first hour of the tide, the flow rate is negligible, but during the third and fourth hours, the rate can be a great deal stronger. Remember too that a spring tide will produce a stronger flow and a neap tide a weaker one.

When I completed my Yachtmaster exam, one of my fellow mariners was a great guy from Australia who had over a million sea miles under his belt. I learnt so much from his professional experience and his practical application of knowledge. But amazingly, he actually failed the exam because he just couldn’t get his head around the technicalities of the tides. This was largely due to the fact that he’d mostly sailed in the waters off South-West Australia, where the tides, being less than a metre in their range, have minimal influence.

The Corryvreckan Whirlpool is reputedly the third largest in the world

Wind over tide

Not only does tidal flow make a significant difference to your speed ‘over the ground’ (seabed), but if you factor in wind against tide, this really does affect the comfort of the trip. Getting it wrong can even cause significant damage to your boat, as we found to our cost once on a return passage from the Scilly Isles. The weather forecast predicted around 20 knots of wind, nothing too out of the ordinary for this sea area, but what we hadn’t factored in was its direction in relation to the tide. As a consequence, we found ourselves traversing a huge sea with breaking crests, which at times demanded some bold and very careful negotiation. The smallest of the two RIBs I was travelling with became overwhelmed at one point by a wave that washed the helmsman clean out of his seat! A ‘plan B’ needed to be hastily devised, so we transferred the somewhat shaken crew into one of the larger RIBs, whereupon I took charge of the swamped boat, got it up onto the plane and altered course for Falmouth. Upon gaining the harbour, we made the boats fast and, you’ve guessed it, waited for the tide to change! After a rest and a well-earned cup of tea, our little flotilla then continued on its way to Fowey with the wind and tide now in its favour.

Top tips for planning your passage

- Know the times of high and low water

- Is it springs or neaps?

- Check out the tidal flow

- Check the direction of the wind

- Check the sea state (the inshore forecast will help)

- Plan your passage around headlands with the tide in mind

The west of Scotland enjoys a great many regions of special maritime hazard

Headlands and channels

Tidal flows are at their strongest mid-cycle, at pinch points such as narrow channels and headlands. In Ramsey Sound off the Pembrokeshire coast, for example, a submerged reef juts out from Ramsey Island and stretches halfway across the channel. The channel, known as ‘The Bitches’, runs at a steady 47-metre depth either side of the reef. However, the seabed shallows to just 6 metres in and around the reef, which essentially creates a dam effect. Just imagine the huge mass of water rushing in from the Atlantic, surging around this foot of Wales, seeking with unstoppable force to find a way up into the Irish Sea. The tide can reach up to 12 knots through ‘The Bitches’ on a spring tide. Furthermore, the water surging through here results in an upward flow of up to 10° as the sheer volume of water is pushed up from the seabed below. It’s a phenomenal sight – just have a look at this great YouTube video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wZZ7Uc3qcM. This footage demonstrates the effect the reef has on the water traversing over it. But if your vessel is making a good 24 knots against this strength of tide, your speed will be halved. Aside from reduced speed, my concern as a lifeboatman of over 30 years would be engine failure and how quickly a vessel could be carried down tide. ‘The Bitches’ is an extreme example, but it’s by no means unique. Furthermore, it goes without saying that a strong wind-against-tide situation in a sea area of this type could be life-threatening, and such a scenario should be avoided at all cost.

The Bitches tidal race Ramsey Sound Pembrokeshire Wales.

Watch for the meeting of conflicting wave crests!

Navigating a harbour mouth can likewise present challenges. On the surface, one sees an even body of water, but of course, beneath your hull the seabed reflects the land and its geological make-up. A harbour mouth invariably represents a shallowing point, and this reduction in depth means that if the tide is on the flood, the ocean pushing up into this narrowing and ever-shallowing confine equals a huge amount of energy and water volume. To illustrate the latter, think of a cubic metre of water: 1 metre x 1 metre x 1 metre. If you put that on a scale, this represents 1 metric tonne. Imagine, then, the hundreds of millions of metric tonnes flowing into a harbour or estuary each day. In the process, the water will start to surge as theseabed shallows and the route in progressively narrows. The flow is therefore accelerated, and if subjected to a contrary wind, its intensified energy becomes even more agitated. In seeking a means of release, invariably it will be dissipated upward and manifest itself in the form of waves, often breaking. This effect can often become even more severe and evident when the tide is exiting an estuary, when the huge body of water rushing out may be subject to a contrary wind. In such conditions, over the likes of a sand bar, you may find surf forming and what appear to be standing waves. In the case of Strangford Lough on the County Down coast, the narrow neck that forms the lough’s inlet is an extreme pinch point. Particularly when the tide is on the ebb, Strangford’s narrow inlet intensifies the flow of water to the degree that it can reach a staggering 4 metres per second! As in the case of ‘The Bitches’, navigating through such an intense area of water is an experience that stays with you for a lifetime.

Thunder Child II leaving Cork in storm Brendan

A race against time

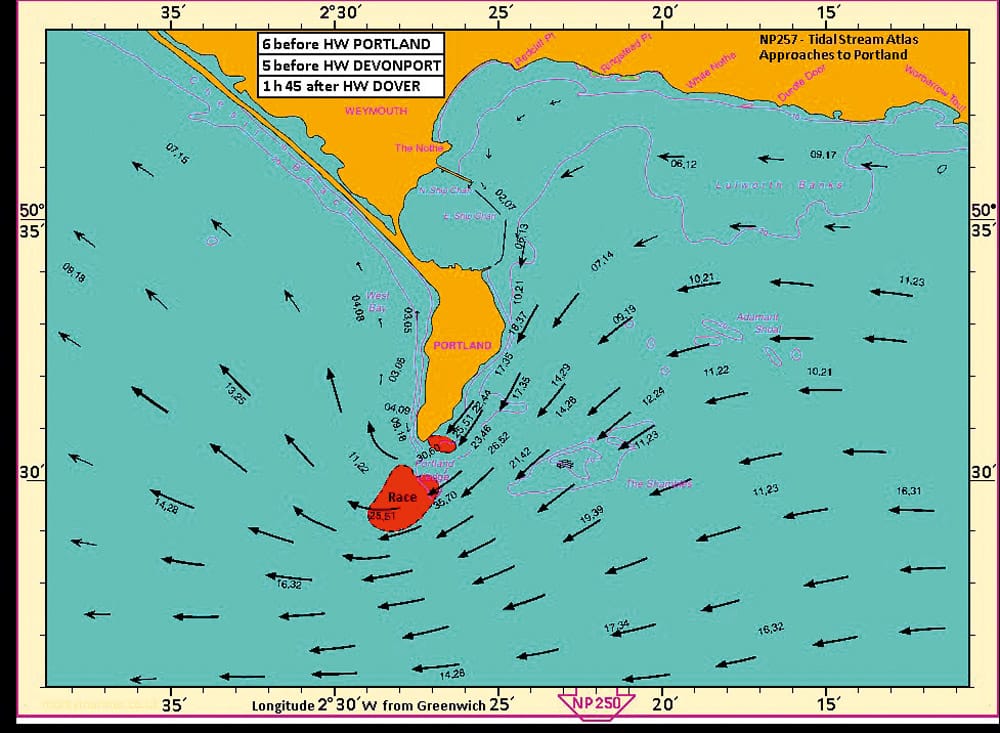

I was recently chatting to an old friend who served on the auxiliary crew of the Weymouth lifeboat. He recalled a shout that involved a superyacht tender that suffered difficulties in the Portland Race. It was a fair summer’s day and the 12m superyacht RIB tender with two professional crewmen aboard was enjoying good progress across Lyme Bay, en route to rendezvous with its mother ship in the Solent. As the crew motored along at a steady 25 knots, the last of the flood tide made for a benign sea, which did little to disturb the pleasant, if not uneventful, eastbound passage. Unfortunately for them, however, things were about to take a dramatic turn for the worse, for their timing was about to coincide with a severe change of the tide. On their approach to Portland Bill, the tidal stream around the promontory nudged the vessel ever more into the tidal race, as the spring tide began to rush back down the channel, westbound. Exaggerated by an underwater ridge that juts 1.5 miles out from the hook of the Bill, the sea lost no time in becoming angry and confused. The crew quickly found themselves amid short-distance waves, vastly different to the calm conditions they had experienced a few miles back. Accordingly they reduced their speed, but the vessel began to take on water as the seas crashed relentlessly over its sponsons. Due to design failings, the inboard diesel’s engine compartment began to be compromised, resulting in it becoming swamped, which then led to the engine and the boat’s electrics being knocked out. The lifeboat launched and thankfully brought both boat and crew safely to the tranquillity of Weymouth Harbour.

Use an anchored object to check on the tidal flow

Aside from the issues relating to the engine housing’s vulnerability, the lesson to be learnt was one of timing and an underestimating of the tide in relation to this notorious sea area. A better course navigated would have been wise (either standing off 5 miles or passing directly beneath the Bill’s cliff face), but certainly an appreciation of the effects of a wind against tide, particularly in this critical part of the passage, would have proved most beneficial. After all, tides are all about timing.

Tidal accumulator

This chart shows where the topography of the land captures the tide. Because the water has nowhere else to go, it builds up, resulting in high tides. For example, in Saint-Malo, the highest astronomical tide reaches 11 metres.

Portland Race Tidal Chart showing the flow into the Race up to 6 knots at Spring tide

In conclusion

Tides are a fascinating example of the forces at play within nature. They are inescapable, and as we have seen, especially when subject to wind, tides have a huge bearing on sea state. Of course, there is so much more that we could discuss, but hopefully this anecdotal overview may serve to prompt you to consider the effect tides have, even when navigating high-powered craft. Undoubtedly, for all of us, it’s worth taking the time to research, learn and understand tides in order to work with them. If you do, you’ll benefit from more comfortable passage making, greater safety and increased fuel economy. And the next time you navigate an airport travelator, remember, go with the flow!

The Seaward is a purposeful looking boat. As the old saying goes, if it looks right, it is right.

Tidal range

Tidal range is the difference between the heights of high and low water. The velocity of the ebb and flow is increased on a spring tide and decreased on an ebb tide.

Springs

- The high tides are high.

- The low tides are low.

Neaps

- The high tides are low.

- The low tides are high.

My top 4 apps

Navionics: £34.99

Basically a chartplotter on your phone, this app is invaluable for passage planning and has real-time weather data, forecasts, wind, tides and currents.

- Pros: I particularly like the slider that shows the tidal flow around headlands in great detail minute by minute.

- Cons: You may think this pricey, but it covers the UK, Ireland and Holland, and quite honestly, if you think you won’t use the app and get your money’s worth because you don’t use your boat too often, think again! If you aren’t a seasoned boater, then you do need as much information as possible.

Boatie: £4.99 standard / £6.49 7-day tidal curves

This is a great all-round app with clear and easy-to-use tidal charts and at-a-glance information on the tide, wind and weather.

- Pros: It gives you the inshore and offshore forecasts and has interactive tidal curves.

- Cons: The tidal flow atlas is more basic, with the weight of the arrows denoting tidal flow rather than showing actual knots of tide, but it’s great for at-a-glance knowledge.

Tide Pro: £1.79

An app that simply tells you the tide times and allows you to put in your favourite locations.

- Pros: It works really well with my Apple watch, so I can see the tide times and state of the tide at a glance.

- Cons: Really basic information, but by checking the heights of the tide you at least know if there’s going to be beach or not when you arrive!

Windy: Free

There is a pro version, but as a free app you can’t beat this one for detailed information on the wind direction and force.

- Pros: You can set the information you need, such as wind, and the app will ‘play’ the information on the map for the coming days, so it’s really easy to see if wind is something you’re going to need to factor in. It also shows wave swell, weather and temperature.

- Cons: None, it’s free!

How do tides work?

Half-daily pattern

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels, and on North Atlantic coasts there are two tides a day (a semi-diurnal pattern). During a full or new moon, the difference between the high and low tides is at its greatest and occurs when the earth, sun and moon are in a line creating a strong gravitational pull. Just as the earth pulls water downwards (in waterfalls, for example), the weaker gravitational pull of the sun and moon pulls water sideways across the earth.

Half-monthly pattern – springs and neaps

Roughly once a fortnight, the sun’s tides coincide with those of the moon to produce strong spring tides. Rather than a reference to a season, the term is derived from the concept of the tide ‘springing forth’. Neaps are low tides, or lower than average, and happen between two spring tides when the first and last quarter of the moon appear. The moon faces the earth at a right angle to the sun, so the gravitational forces of the moon and sun work against each other. The term ‘neaps’ is derived from an old English word ‘nep’, meaning ‘to become lower’.

Effects on the tide

Astronomical factors that control the tide can be predicted years ahead, but bear in mind other factors that have a distinct effect on tide:

- High barometric pressure can lower the sea level; unusually low pressure can raise it.

- Onshore wind, or wind that is being funnelled up an estuary, tends to push water with it, producing high waters that are slightly earlier and higher, and low waters that are slightly later than expected.

- Wind, pressure and geography can combine to produce surges that can raise or lower the sea level.