Paul Glatzel continues his examination of the processes involved in berthing …

In our last article we started to look at the challenges we all have when coming alongside marina berths. We looked at how we gather the information we need to start to get a plan together, referring to this as the ‘assessment’ phase.

As part of the last article, we considered specifically how our boat handles and developed an understanding of how the elements (wind and tide/stream) influence our craft. The final part of the assessment phase is to look at the berth we are interested in and determine how the elements impact an approach to that particular berth.

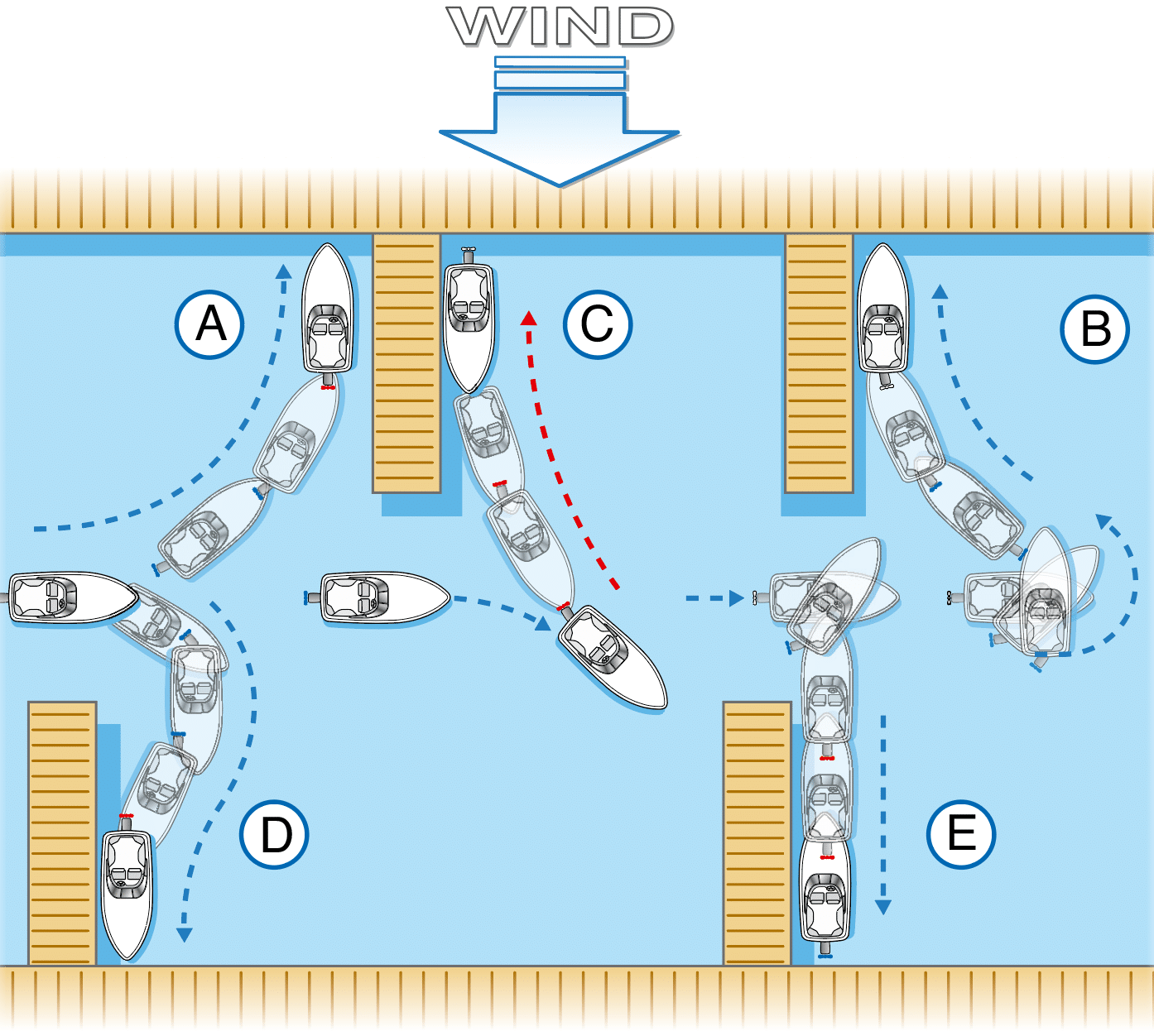

Let’s look at a few marina berths to assess the issues we are likely to face when approaching some berths and so create a plan of approach that will (hopefully!) work.

Berth A: As we established in the last article, our powerboats are only ‘happy’ when they are side (‘beam’) on to the wind. We also determined that with many powerboats with light bows and heavy sterns, the bow can be very quick to rotate from pointing into the wind to lying side on. Therefore, with Berth A we need to keep a careful watch on the bow, as when we approach the berth bow into wind, the bow naturally wants to rotate either towards the pontoon or to the left where another boat may be berthed. Our approach from the left-hand side of the marina also means the berth is ‘open faced’ and so fully visible to us. Approaching from this angle allows us to carry momentum onto the berth, but we need to be careful not to overdo things. As we approach ‘A’, we need to time our turn and come to a stop so we are not sliding sideways past the berth. Knowing when to turn is a matter of learning about your boat and lots of practice. In summary: slow down, time the turn, get a nice angle onto the pontoon, control the bow.

Berth B is obviously very similar to A, but from our approach direction, the berth is ‘closed faced’ to us. There is no absolute right or wrong way to approach, but a good method is to go just past, turn to get a good angle of approach and enter the berth. The rest of the things to think about are the same as for A.

Safely alongside © Alex Whittaker

Berth C can be a straightforward berth to get into if you set yourself up right. Powerboats generally don’t need much effort to keep them holding ‘stern to wind’, therefore, as long as you turn at the right time, you can gently ease yourself stern first into the berth. As you approach the berth, I would tend to stay slightly to the left of the channel (the ‘upwind’ side) to give yourself some room for the turn and ensure that you are not blown side on down onto the boats to your right – the ‘danger side’. The image shows a small turn initially to the right, then a reverse into the wind, but it can work just as well without that turn to the right but with an initial turn to the left (port) and a reverse to start the turn and arrest forward movement in one move. Try both and see what you think.

Heading into Berth D at first glance may seem simple as the wind is behind you, but there is a need to be careful for a few reasons. In the example shown, the powerboat heads straight into the berth. Another option is to go past the berth, turn and the berth becomes ‘open faced’. Be careful on the turn, though, as if you get side on you may get blown on to the other boats quickly. Also, it’s easy to head into the berth too fast, so get into position with the stern into the wind and ease in slowly.

Berth E can be a tricky berth. The problem with this berth is the need to hold the bow into the wind as you reverse into the berth. As we have already established, the wind wants to push the bow off to the left or right, so we need to juggle reversing in the wind, potentially increasing our momentum, and keeping the bow under control. This is precisely where a bow thruster is worth its weight in gold. With or without a thruster, there is a need to fender well before approaching and time your turn so that you don’t have to reverse too far towards the berth.

Remember, with any of these berths a good skipper knows when to pull the plug and abort. For E, it may be that bows in first makes more sense, or perhaps speaking to the marina and going alongside in a really simple berth and moving the boat when the wind eases. Whatever you decide to do, remember two things: 1) there is no shame in deciding not to approach a berth in the conditions you face; 2) the boat is only plastic and can be repaired – keep hands and legs clear. Only use fenders to fend off.

With any approach and berth, consider following this process:

• Assess the wind, tide, depth and impact of other vessels

• Plan the approach factoring in this assessment

• Execute the approach but ensure that you have an escape route planned in too

As we have said many times, you won’t get good at this without practice. Start with lots of turns through 180°, then find a long straight pontoon and practise coming really well alongside at a set location. Then progress to finger berths – find a double one free of other boats and pretend there is a boat in the other berth. Go into it again and again until it becomes easier, then find another berth and go again. Start by doing this with no wind, then with a little bit, then with a bit more. If need be, get a good instructor out with you to hone those skills.

Remember, things will go wrong from time to time. Don’t power out of a problem, and if you are going to ‘crash’, do it slowly. Finally, not every coming alongside will be ‘pretty’ – just make sure it’s safe. Have fun afloat!

Bow thrusters – they’re cheating, aren’t they?

Let’s nail this one – no they aren’t, and any old salty seadog that tells you otherwise needs to get real. The thing about bow thrusters is to use them in the right way. The bow thruster should be used as a means to tidy things up, not to achieve the objective. For example, let’s say you are turning through 180° to return back in the opposite direction. Aim to achieve the turn using engines and steering, and add the bow thruster in to tidy up the turn if needed. What you don’t want to be doing is using the bow thruster to fully turn the bow, as that risks overloading a system drawing a high current and also risks the bow thruster ‘tripping’ just when you really need it. If you struggle to do the turn without the use of a thruster, then it’s well worth a few hours with an instructor to develop the skills to do the turn without relying on the thruster.

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK and Marine Education in Poole and Lymington (www.powerboattraininguk.co.uk / www.marine-education.co.uk).

Paul Glatzel is an RYA powerboat trainer and wrote the RYA Powerboat Handbook and the RYA Advanced Powerboat Handbook. He runs Powerboat Training UK and Marine Education in Poole and Lymington (www.powerboattraininguk.co.uk / www.marine-education.co.uk).