Planning on undertaking a passage in really bad weather is foolhardy, but developing your skills to be able to cope with more challenging conditions is a key part of enhancing your capability as a skipper, as Paul Glatzel explains …

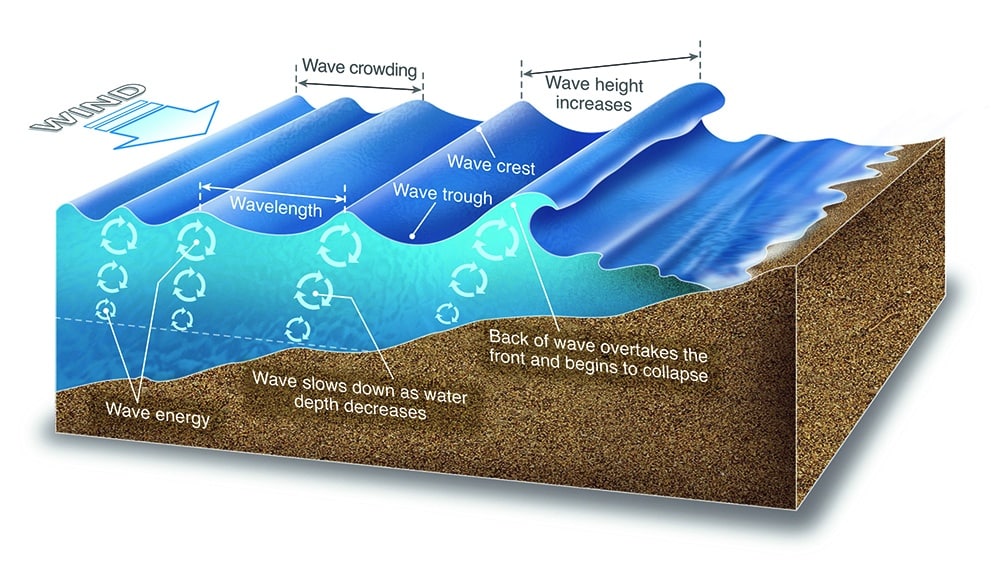

Comprehending some of the key wave characteristics is key in understanding how to interact with, and react to, the waves you will face afloat.

There’s no doubt that nothing beats hands-on experience of any aspect of boating, but to make the most of your time afloat, understanding the theory behind handling rougher conditions makes sense before you put to sea.

Before looking at actually handling the waves, let’s explore some of the theory behind the waves themselves, what forms them and what you may need to consider when engaging with them.

For waves created by wind, the size of the waves will be a function of the distance over the water over which the wind blows (‘the fetch’) combined with its strength and how long it’s been blowing. If there are tide-generated waves, the rate and direction coupled with the bottom profile all combine to determine the magnitude of the waves created. Really challenging sea conditions may arise where wind and tide-generated waves interact. By interpreting tidal information, tidally generated waves are generally predictable, and by checking the weather forecast and weather over the previous few days you will be able to predict what wind-driven waves are likely to be faced. Combining this information gives you an idea of what conditions you will experience, and so it may be possible to work around or plan for the conditions.

‘Reading the sea is a key skill to develop’

Comprehending some of the key wave characteristics is key in understanding how to interact with, and react to, the waves you will face afloat.

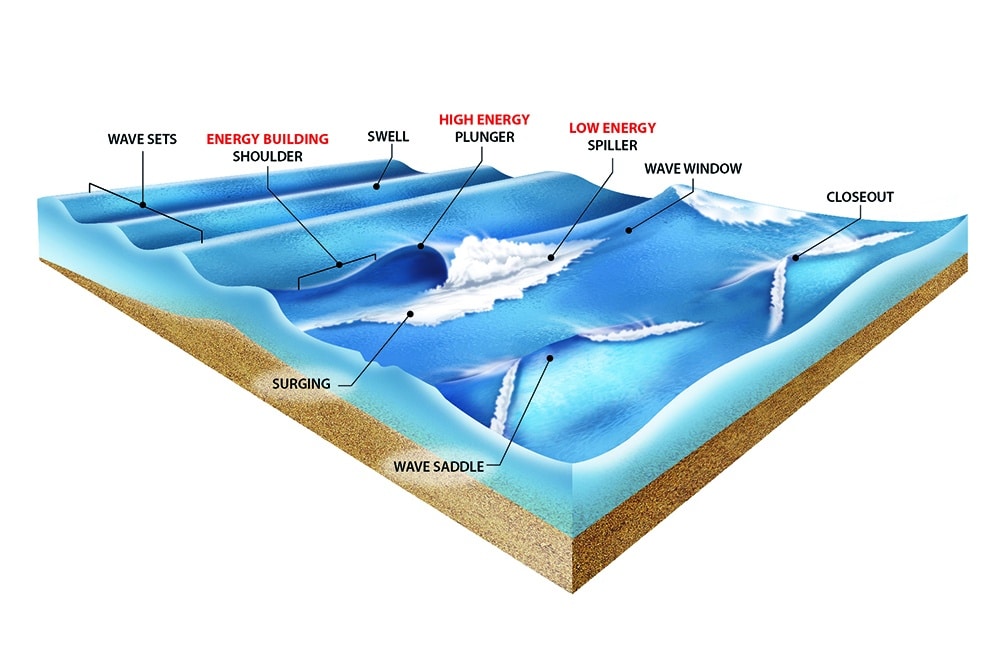

In any area of rougher water there will be ‘wave saddles’ and ‘closeouts’ and also frequent gaps in the waves – known as ‘wave windows’. Waves that break present the biggest potential danger and challenge as the energy they contain can be substantial. In the moments immediately before breaking, the energy level is at its highest, and the last place you want to be with your boat is where the wave can ‘plunge’ onto the craft. Often, though, when at sea you don’t see full breaking waves but waves that are ‘spilling’ their energy and dissipating as they ‘surge’.

Identifying a path through the waves is one of the key skills to develop as a skipper, as avoiding interacting with waves and skirting round them will often be a good option. It may be that by slowing your approach or stopping you will be able to let a wave break in front of you so that its energy has a chance to dissipate before you move through where it is. As skipper, you will constantly need to be scanning the sea to see what waves are developing, which may be about to break and thus what your route through them should be.

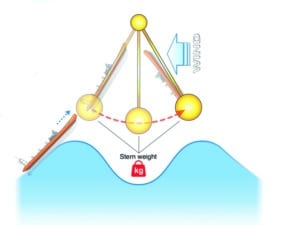

‘Pendulum effect – caused by excess speed’

When travelling in rougher conditions, you will be faced with three potential ‘types’ of sea: a ‘head sea’ (or ‘up sea’) is where you are heading into the wind; a ‘following sea’ or ‘down sea’ is with the wind behind you; and a ‘beam sea’ is with the wind on your beam. Heading upwind you will want to generally trim the bow down to allow the V shape of the hull to slice through the waves. Your approach will be to power up the wave, easing the throttle off at the crest to let the bow drop, then power down the back of the wave and up the next.

In rougher conditions, one danger may be that the skipper chooses to travel with too much speed, hits a wave and the craft is sent vertical. Heading into the wind, the bow may be held up and the weight at the stern causes the stern to follow through – this is known as the ‘pendulum effect’. If the stern catches a wave, the craft may land hull down, but the impact could be considerable, and if the engine doesn’t catch a wave, the craft could turn over. Slowing down reduces the chances of this occurring.

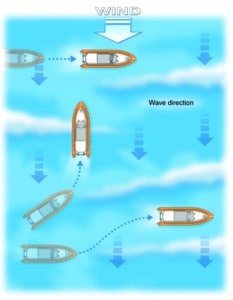

‘Choosing a path in a beam sea’

Running ‘down sea’ (or in a ‘following sea’) often catches skippers unaware as they misjudge driving the craft and ‘stuff’ the bow into a wave with potentially catastrophic consequences. To set up the boat, ‘trim up’ to raise the bow, and try and ride on the back of a wave until it breaks/dissipates – if you have a choice of waves, choose the biggest one as it gives you better vision downwind. The risk with travelling downwind is that if you power over the back of a wave, there may be a large drop and a ‘hole’ awaiting you. As the bow drops into the hole, it stuffs, and the boat stops and then possibly gets rotated by the next wave and then rolled. When side on to breaking waves, a wave height equal to roughly the beam of the boat could roll it. Even if you don’t get rolled, the dramatic drop can easily cause injuries.

Running in a ‘beam sea’ creates different challenges. Often progress can be quite good, and the trick is to find a path through the waves by varying throttle and steering. Keep a really good eye out upwind, though, as you don’t want to be caught out by a breaking wave. Make sure that you always have reserves of power as you need to have the option to be able to power away from a problem if necessary.

Developing your capability in rougher conditions doesn’t need to occur in big waves, and initially getting experience in higher wind conditions in harbours and estuaries is really beneficial. After all, you may be a whizz at managing the throttles in rougher conditions and finding a good route through the waves, but if you cannot helm the craft in close-quarter situations with the same degree of competence, you are missing a trick. Get out when the winds are higher and practise all of the same skills you tried when you were a far less experienced boater – approaching mooring buoys and pontoons where wind and tide are pushing you off, difficult finger berths and, of course, man overboard. Practise all the difficult skills and look to ‘read’ the wind as it passes over the water. Then start to move through smaller waves, practising all of the skills outlined above. Getting your use of throttles and steering nicely coordinated is a real skill to develop.

While getting out in windier, rougher conditions helps develop your skills, it comes with increased risks, and you must be careful not to give rise to a lifeboat call-out. Travel in company, ensure someone ashore knows where you are going, and appreciate your limitations and those of your craft.