Putting your boat alongside a pontoon, dock or jetty is one thing, but how do you make the coming away relaxing and simple? Like any boating manoeuvre, it’s down to forethought, planning and understanding the dynamics of what’s happening to your boat, plus a bit of practice too, as Paul Glatzel explains …

For many powerboaters, leaving a berth can be a really stressful experience in which they’re just happy if they don’t twang the gelcoat or scuff the tubes by dragging the stern of the boat against the wall/pontoon as they leave. It doesn’t need to be that way, though, so in this article we’ll make sure you know the tricks and techniques so that those watching you are amazed how easy you make it look. While the article is based on outboard/outdrive craft, many of the methods work for shaft drives too.

Like any manoeuvre we undertake on the water, the place to start is to take a step back and think things through. Remember in the first article we introduced the idea of APE (Assess – wind, tide, depth, other craft; Plan – in light of the assessment create a plan; Execute – then you can go ahead, but always have an escape route). It’s just the same with leaving a pontoon, as what the wind and tide/stream are doing will have a key bearing on how you choose to leave the berth, and you need to create a plan that addresses these factors.

Assuming that you have considered depth and the presence of other craft, the key things to consider will be wind and tide/stream. Are they pushing the vessel off or on to the pontoon, or perhaps pushing against the rear (stern) or the front (bow) of the craft?

Let’s start by assuming the forces are pushing you directly off whatever you are attached to. If this is the case, you have a couple of simple options.

Top tip: When preparing to leave a pontoon, get your crew to rig the bow and stern lines so they go around the cleat (or through a mooring ring) and back to the vessel. This allows the crew to release the lines from within the boat rather than untying then leaping on board. It’s safer and more relaxing for everyone and is good seamanship.

The simplest method is often just to release your bow and stern lines and let the elements push you away from the pontoon. Make sure, though, that you are properly clear of the pontoon before you turn the wheel and engage forward gear or else you risk the stern being pushed towards, and possibly engaging with, the pontoon. (Note: This is all down to pivot points. Remember in the first article we established that it you turn the wheel, then engage gear, the front third of the boat goes where you intend it to but everything behind that will be pushed the other way. Forgetting this is precisely why so many helmsmen end up with damaged or scuffed sterns. The good thing is it’s easy to deal with, though.)

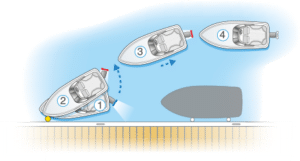

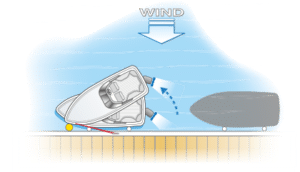

Being pushed off may not always work, or the elements may not be directly to your side, so you will need to be able to use another technique – reversing away from the pontoon. To make this go smoothly, follow a few simple steps: 1) Rig the lines ready to let go; 2) Turn your wheel away from the pontoon; 3) Check all around, release the lines, and once the helmsman is 100 per cent sure that the lines are clear and back on board and the crew are safely positioned, engage reverse (astern). The shape of the bow allows the boat to pull away from the pontoon without the bow touching. Whether you alternate between reverse and neutral to pull yourself away or you leave the throttle in reverse for a longer period is a bit of a judgement call. With wind off the pontoon or not having much effect, alternating is best. The aim is to reverse the boat in an ‘S’ shape away from the pontoon until it is well clear so you can then move off ahead. See Image: Reversing off

Being pushed off may not always work, or the elements may not be directly to your side, so you will need to be able to use another technique – reversing away from the pontoon. To make this go smoothly, follow a few simple steps: 1) Rig the lines ready to let go; 2) Turn your wheel away from the pontoon; 3) Check all around, release the lines, and once the helmsman is 100 per cent sure that the lines are clear and back on board and the crew are safely positioned, engage reverse (astern). The shape of the bow allows the boat to pull away from the pontoon without the bow touching. Whether you alternate between reverse and neutral to pull yourself away or you leave the throttle in reverse for a longer period is a bit of a judgement call. With wind off the pontoon or not having much effect, alternating is best. The aim is to reverse the boat in an ‘S’ shape away from the pontoon until it is well clear so you can then move off ahead. See Image: Reversing off

Top tip: If space is limited behind you, it may be necessary to reverse away from the pontoon at a more pronounced angle. If this is the case, consider inserting an extra step into the manoeuvre by initially turning the wheel towards the pontoon and engaging forward gear for about half a second. Immediately you are back in neutral, rapidly steer away from the pontoon and follow the procedure already explained. This gets the stern further from the pontoon for that more pronounced angle of exit.

The above method is based on you wishing to move off ultimately in a forward direction. If you wish to go the other way, you have two options. If you want, you could just use the technique outlined, move off forward, then find a place to turn round. Another option is to do a U-turn in reverse – assuming you have enough space. Rather than reversing out in an ‘S’ shape, leave the throttle in reverse for longer – you will be able to achieve a full U-turn, or at least most of it, in a space of about two boat lengths. Try this in clear water to get the idea, then give it a go yourself.

If the wind/stream is onto the pontoon, your strategy for leaving will depend on how strong these elements are. A good percentage of the time – except where the elements are strong – you may be able to just use the technique outlined above, with the only difference being the need to keep the throttle in reverse gear a bit longer, as if you spend too long in neutral you may just be blown/pushed back alongside the pontoon. Getting the stern out initially using the ‘top tip’ outlined may make all the difference in these conditions.

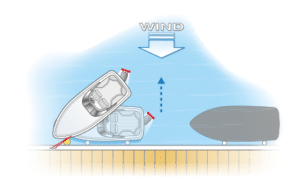

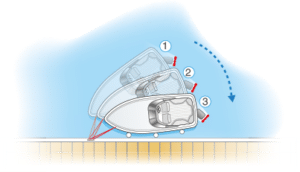

If you are really pinned on, there will almost certainly be a need to use lines to ‘spring’ off the berth. The idea of a spring line is that it limits your forward or rearward movement and allows you to get the stern pointing out into the elements so that you can successfully reverse away. Let’s look at an example. See Image: Using a back spring to reverse off

If you are really pinned on, there will almost certainly be a need to use lines to ‘spring’ off the berth. The idea of a spring line is that it limits your forward or rearward movement and allows you to get the stern pointing out into the elements so that you can successfully reverse away. Let’s look at an example. See Image: Using a back spring to reverse off

Follow these steps: 1) Rig a line from a cleat or bollard at the bow around a cleat or through a mooring ring ashore and bring it back to the cleat/bollard; 2) Take a turn around the cleat and secure the line; 3) Release the stern line and gently take up the strain on the spring using reverse; 4) As tension comes on the line, engage astern and leave it in gear; 5) Turn the steering away from the pontoon and the stern will start to lift clear.

When the boat is nearly at 90° to the pontoon, there needs to be a coordinated effort between the person controlling the line and the helmsman – agree this in advance to avoid misunderstandings. 1) Go to neutral; 2) Tell the person at the bow to release the line from the cleat and rapidly pull it back on board; 3) When the line is back on board and the person at the bow safe, gently engage reverse to move away.

Top tip: In my experience, in most craft – except in very strong winds or with boats close ahead/behind – there is not too often a need to use a spring. After all, if you can get away without springs, it may make things simpler for you. Experiment in your boat to see what works, but try to keep things as simple as possible.

There are a couple of risks with this manoeuvre that merit consideration: 1) The person at the bow must secure the line and never take the load from the spring line in their hands; 2) If on the foredeck of a boat a rapid movement of the craft could lead to a person in the water, keep throttle movements gentle and make sure they keep their centre of gravity low and hold on.

Safety point: If you are going to put load onto a deck cleat or a cleat on a pontoon or a mooring ring, make sure it is up to the job and securely attached.

Another way to spring away is to rig a spring line that arrests the forward movement of the vessel, as in the image. This can work well but assumes that you can fender the boat well as you will be pushing the craft against the pontoon, in contrast to the other method where you are pulling it away. See Image: Using a forward spring

Another way to spring away is to rig a spring line that arrests the forward movement of the vessel, as in the image. This can work well but assumes that you can fender the boat well as you will be pushing the craft against the pontoon, in contrast to the other method where you are pulling it away. See Image: Using a forward spring

Two other wind/stream directions may act on you when you are tied up and seeking to leave. If the wind/stream is directly behind you, reversing into these elements should be pretty straightforward using the methods already outlined. If the wind is directly on the bow or slightly to one side pushing it onto the pontoon, this can create an additional challenge as when you seek to reverse away, the wind wants to rotate the vessel to side on to the wind, thereby forcing the bow towards the pontoon and risking hitting it as you pull away. There are a few options: 1) Reverse away more positively if there is space by keeping the throttle in reverse for longer to get the bow clear; 2) Spring away in reverse; 3) If the wind is on the bow directly it may be possible to ease it away from the pontoon slightly so the wind then rotates the bow away. Keep an eye on the stern, and when an exit angle appears ease forward slowly.

While this article is mainly about leaving a pontoon, let’s also quickly look at using springs to get alongside. The principle is much the same as outlined, which is to use a line to constrain the craft, allowing you to drive it alongside the pontoon. Two methods work well.

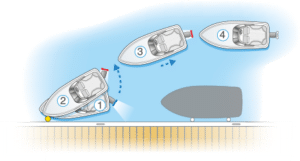

Drive up to a cleat and follow this method: 1) Lasso a line around the cleat; 2) Secure it onto the craft – leave 2–3 metres of line between the bow and the pontoon to allow the craft to rotate; 3) Take up slack, engage reverse; 4) Steer towards the pontoon; 5) As the stern comes towards the pontoon, lessen the speed of movement of the stern by straightening the wheel; 6) Secure the stern line to the pontoon. See Image: Driving forward towards pontoon

Drive up to a cleat and follow this method: 1) Lasso a line around the cleat; 2) Secure it onto the craft – leave 2–3 metres of line between the bow and the pontoon to allow the craft to rotate; 3) Take up slack, engage reverse; 4) Steer towards the pontoon; 5) As the stern comes towards the pontoon, lessen the speed of movement of the stern by straightening the wheel; 6) Secure the stern line to the pontoon. See Image: Driving forward towards pontoon

If access to the bow is challenging, you can do the same but by reversing towards the pontoon. Apply the same method already used but use forward instead of reverse. Make sure, though, that you leave enough line to keep the stern/prop clear of the pontoon. See Image: Reversing towards pontoon

If access to the bow is challenging, you can do the same but by reversing towards the pontoon. Apply the same method already used but use forward instead of reverse. Make sure, though, that you leave enough line to keep the stern/prop clear of the pontoon. See Image: Reversing towards pontoon

Like anything boating related, practice makes perfect, so why not get out there and try out these techniques … Have fun!